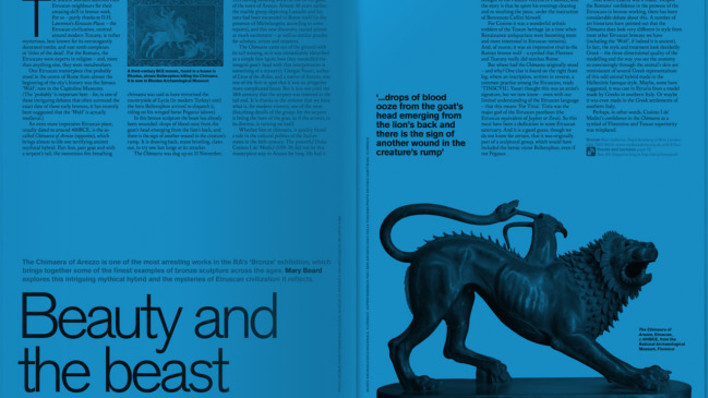

In the studio: Peter Barber RA

By Sarah Handelman

Published on 26 July 2023

The architect renowned for his social housing projects operates from a converted 19th-century shop in King’s Cross. He gives Sarah Handelman a tour.

From the Summer 2023 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

It seems only appropriate that a man named Peter Barber should run his practice out of a shop. The symbol of his trade, however, is not the striped barbershop pole but a window stacked high with shelves of architectural models. Set just a few metres off London’s busy King’s Cross Road, Barber’s shopfront suggests a kind of high-rise city in miniature, beckoning passers-by to stop for a moment and gaze into another world. Here models of roughcut foam, delicate card and candy-coloured ceramic stand in for his eponymous office’s projects, among them proposals for imagined neighbourhoods, as well as the innumerable social and affordable housing schemes that are his specialism. It is the latter that, in recent years, have made Barber one of Britain’s most celebrated and distinctive architects.

A central tenet of Barber’s small-scale practice of six is the importance of the street in architecture and its role in public life. So it comes as a welcome surprise to find that Barber’s practice – both the work of the office and the space where that work happens – is precisely what he preaches.

“There’s a responsibility that comes with having a shopfront,” Barber says as he greets me, his 6ft-plus frame gently towering in the doorway. “We look out as much as the people who look in – and all kinds of people come in: tourists, students, homeless people, even journalists! It’s our interface with the city.”

Beyond the front window, dozens more models hang on the walls of the listed 19th century building the office has called home for the past 20 years. Far from the clean lines and open-plan layouts typical of many architects’ spaces, there is a refreshing irregularity to the interiors, an almost Dickensian house of cramped quarters, uneven floorboards and steep winding stairs.

The architect himself is a kind of latter-day incarnation of the Victorian writer, as someone who both sets the scenes for life to happen while challenging existing conditions. “There are 500,000 empty homes in the UK and 10,000 empty homes in London,” he says. “One doesn’t feel endlessly comfortable about it, and that’s why I’ve dipped my toe into the broader political discussion which I think needs to be addressed.” Barber is the author of a number of speculative architectural and planning proposals, including the recent ‘8,000-Mile Island’, which reimagines the most depopulated areas in the country – notably Britain’s coastline – as hubs of 21st-century farming, energy and industry. “All of a sudden these areas could become really attractive to people work-wise,” he explains, “which means they could feel able to leave overpopulated London and live in these extraordinary places.”

We love it when everyday life spills out from the front doors of our finished projects.

Peter Barber RA

Barber has helped to transform parts of London too, turning some of the city’s most awkward, unwanted and seemingly unusable plots of land into community oases that have prompted councils and housing associations to take note. Drawing on both modern and premodern architectural forms and housing types – from vaulted roofs and courtyards to mansion blocks and mews – there is a familiar quality in his projects but also, as he says, “a certain dreaminess”. In east London, for example, the award-winning McGrath Road, which provides 26 homes, all with social or affordable rent or shared ownership, emerges as if from a De Chirico painting. Set flush against the street, a series of sweeping arches topped by a crenelated roof evoke a fortress, albeit made playful by rounded corners, balconies and a warmth of materials and colour. The shared inner courtyard is overlooked by more balconies, while the front doors, each with their own areas for potted plants, are reinvigorated as threshold spaces of personal identity and social exchange.

Whereas much UK housing is delivered as architectural fast-food, erected quickly as anonymous and generic apartment blocks, in the hundreds of homes designed by Peter Barber Architects, a sense of humanity remains a constant. It is in the ethos of his office, from how projects are discussed to Barber’s enthusiasm for what happens when residents move into their new homes. “We love it when everyday life spills out from the front doors of our finished projects,” he says. “Some architects hate it but, but the clothes lines, bicycles and plants are what make what we do human. They become more important than the architecture.”

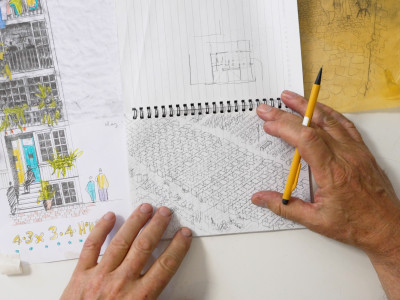

Similarly, the hand – as opposed to the computer – is how projects begin. “The computer generally has no significant role in the early stages of our work. We use a pencil and the design process happens on paper,” says Barber, who starts by laying yellow tracing paper over a site plan, building up the sheets as the design progresses. “For us, drawing tells you something that a render cannot. It communicates the atmosphere, vibe and intention. But if you’re not careful you can kid yourself with a sketch. You have to get it into a physical model because the model doesn’t lie.” Hence the wares of this shop.

Inside Peter Barber's practice

The role of the hand in the production of architecture also forms Barber’s approach to this year’s Summer Exhibition, where he is curating the Architecture Room. Drawing inspiration from the phrase ‘Making is Thinking’, coined by writer and sociologist Richard Sennett, the hang will include large and small-scale work, from ceramics, models, drawings and sketchbooks to site-specific installations, all created by a diverse array of makers from Dorset to Delhi. A tree-supported truss spans half the room, while two pieces by the late Phyllida Barlow RA will vertically divide the space – sculptural gestures, rocketing skyward. For Barber, who began discussing possible interventions with Barlow shortly before her death, the collaboration was an opportunity to “put the cat amongst the pigeons. I thought it would be a way of bridging the gap between art and architecture to see what effect they had on one another. Phyllida’s work is architectural because of its scale, and she gloried in everything that she recycled and reused.”

Such an openness to a variety of handmade processes and outcomes suggests that curating came easily to Barber. As he sees it, the task wasn’t such a departure from his day job: “When we were drawing the space, we realised the plan we were making looked a bit like a city.” And just like the housing he designs or the shopfront world he has created for his neighbours in King’s Cross, he adds, "I hope that people take away their own impressions."

Sarah Handelman is a writer and editor.

Peter Barber hangs the Architecture Room in the Summer Exhibition 2023, 13 June – 20 August.

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

Related articles

Crunch: inside the first Architecture Window display

14 February 2024

RA Architecture Prize Winner 2023: Shane de Blacam

1 September 2023