RA Architecture Prize Winner 2023: Shane de Blacam

By Shane O’Toole

Published on 1 September 2023

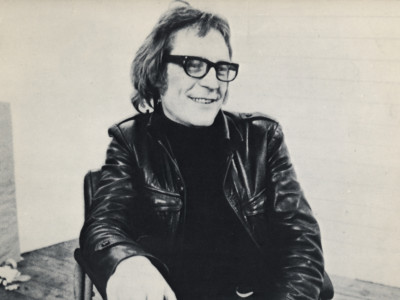

Shane de Blacam’s former student, critic Shane O’Toole, celebrates the architect’s thoughtful transformation of public places across his home country of Ireland.

From the Autumn 2023 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

There is no more respected architect in Ireland than Shane de Blacam. Even Ireland’s Royal Gold Medallists and Pritzker Prize winners are all agreed on that. The practice he founded in 1976 with fellow Irishman John Meagher (1947-2021) has won every accolade going – membership of Aosdána (the national academy of 250 leading artists in Ireland), the Royal Institute of Architects of Ireland’s Gandon Medal for lifetime achievement, the RIAI Triennial Gold Medal for architecture, the equivalent triennial medals for housing and for conservation, a Europa Nostra Medal, the Architectural Association of Ireland’s Downes Medal, selection to represent Ireland at the Venice Biennale, and now he is the winner of the RA Architecture Prize. A clean sweep: nobody else has done that. But that’s not the reason why he is held in such high regard. It is for how he came almost to redefine the supreme role of the architect as one who gives form to the institutions of community: churches, libraries, universities and the like.

Half a century has slipped by since my small cohort and I walked into the basement studio at University College Dublin in 1973 to meet Shane de Blacam, the greatest teacher any of us would ever know. He would make us lay the foundations for a life in architecture. The word ‘make’ is important here. Shane’s belief is that architecture is made through making. Making and making again, each result merely another small step along the way, which is a very long one – even something of a calvary. For him, architecture can never be easy, never quickly arrived at. It takes time to build the necessary density of intention, layer upon overlaid layer. More time than many would admit or permit. A foretaste of what buildings themselves must endure to be of true value. There are some other architects like this. The Swiss Peter Zumthor comes to mind.

Phoenix Park, Dublin. International Competition OPW Prize Entry.

Shane made us tradesmen to our tools. Expert tradesmen. He had us make precise scale models of complex domestic roof structures and their joints, using fine yellow pine sticks he imported from America. When making card or balsa models, he had us throw away scalpel blades after only half a dozen cuts because they were no longer sharp enough and would partly crush the material while we were cutting it. We learned the correct pencil leads to use in any given situation, from 6B to 9H. When making drawings, we had first to set them up accurately in all their detail, then take an overlay sheet of paper and either trace everything again, this time to absolute perfection as a finished drawing or, if making a perspective sketch, improvise – in the style of a jazz musician riffing on a melody – in freehand over the net drawing we had meticulously prepared.

He imposed discipline upon us, insisting upon a library atmosphere while we acquired these practical skills. The studio was engaged in serious work. Silence became a powerful aid for concentration and reflective thought in the making of architecture at every stage of its development. Only years later would it finally dawn on some of us that this is also how we experience great architecture when we encounter it: thoughtfully, in quiet reflection. If this is how architecture is most deeply felt, how could it possibly be made in any other way?

In both new buildings, and sensitive historic restorations, de Blacam’s practice reminds us of the power of craftsmanship to create spaces where we can come together for stillness and reflection.

The 2023 Royal Academy Architecture Awards jury

Shane was then a precocious 28 years old. He hasn’t changed a bit over all the years since. When he was 19 and working a summer job in Lansing, Michigan, he bought a 1949 Buick Roadster and spent weekends touring all of Frank Lloyd Wright’s works in Michigan, Wisconsin and Illinois. He went to Chicago, visiting Oak Park and discovering the work of Mies van der Rohe at the Illinois Institute of Technology and the Lake Shore Drive towers. Later summers were spent in Delft and Aachen attending workshops run by Peter Smithson, Jaap Bakema and other members of the influential thinktank, Team 10, and in London with the firm Chamberlain, Powell and Bon.

But he was always intent on returning to America, which he did in 1969, having won a Fulbright scholarship to pursue postgraduate studies under Louis Kahn at the University of Pennsylvania. He quickly struck up with Kahn, and was soon moonlighting in his office, initially on the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. Following graduation, he was taken on full-time and became centrally involved as Kahn’s assistant in the detailed design of Yale’s Paul Mellon Center for British Art for two years, before returning to Ireland to teach. He was already complete as an architect although he hadn’t built anything yet.

Firhouse, Dublin. Dioceses of Dublin Competition. Prize Entry.

His partner-to-be John Meagher spent his formative postgraduate years in Finland. Widely regarded as the finest draftsman of his era in Ireland and blessed with a couturier’s impeccable eye for beauty, he brought a certain levity and refined sensuality, which complemented Shane’s intensity, to the studio they established together in 1976, after they submitted three entries for the Dublin Diocesan Church Competition and won two premiums.

A small but telling example would be the enormous clam shell, with its allusions to the birth of Venus, that John brought home from south-east Asia to serve as a baptismal font in their first work, the parish church at Firhouse (1978). At Firhouse – and in the Taoiseach’s House, probably the most lamented unbuilt Irish project of the 20th century – Shane and John set out several elements that would become recurring themes during the following 45 years. The Firhouse church comprises a walled garden in which a fully glazed cruciform frame creates four contemplative gardens to surround worshippers, each planted for a different season. In the Taoiseach’s House design, submitted in 1979, gardens form a natural extension to the complex’s libraries. Shane has designed many libraries (the Town Library, Abbeyleix, 2009), with three more currently on his desk. “It is a huge responsibility,” he says, “but an enormous privilege. Public work – the building of institutions – is the highest calling an architect can answer to.”

Abbeyleix, Laois. Appointment Laois County Council.

Much of Shane’s work has been to build or restore institutions. The Cork campus of Munster Technological University (2006) is a brick colossus that elevates the former Institute of Technology – previously occupying a rough conglomeration of crude precast buildings – into a campus worthy of its new status as a Technical University. During the restoration of Trinity College Dublin’s Dining Hall following a catastrophic fire in 1984, Shane found space within the volume of the former 18th-century kitchens to insert a soaring timber atrium in the style of a Spanish theatre to provide rooms for college societies, balancing this student bonus by offering the dons a witty facsimile of Adolf Loos’s bijou American Bar in Vienna.

The expert manipulation of scale – the secret weapon, the extra dimension that heightens and intensifies our experience of architecture – is, more than any other thing, I think, the key to understanding the power of the work of de Blacam and Meagher.

College Quadrangle (circle). Three Buildings: Administration, Tourism and Hospitality, Student Centre.

Appointment CIT with BBMOC

Dining Hall Restoration. Appointment Provost Fellows Scholars TCD

Dining Hall Restoration. Appointment Provost Fellows Scholars TCD

Surprisingly, there is no monograph on their work. Shane is of the opinion that there is too much vanity publishing today and it is not good for architecture. He is making new editions of four large-scale books, however, and a table for their display at the RA. Three of these were exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 2018 and produced in a handmade edition of just two copies. One set is now in the Irish Architectural Archive, the other in the United States.

The books will be illustrated with photographs by Peter Cook and drawings by the office. Not presentation drawings but the drawings that guided the making of the buildings. There will be no texts. Shane has no time for post-rationalisation of his buildings: “Parsing or analysis by others – that is of zero interest to me,” he says. “The visual world is independent of that. It involves the unmeasurable. A building speaks for itself.” Rather like music, it must be experienced directly to be understood.

Shane O’Toole is an architecture critic who wrote for the Irish edition of The Sunday Times for ten years and won the International Committee of Architecture Critics’ triennial CICA Pierre Vago Award for Journalism in 2020.

Shane de Blacam delivers the RA Architecture Prize Lecture at the RA’s Benjamin West Lecture theatre on 31 October.

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

Related articles

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024

10 RA Schools stories through the centuries

16 May 2024

In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

1 May 2024