Jasper Johns: "Take an object. Do something to it. Do something else to it."

By Barbara Rose

Published on 6 September 2017

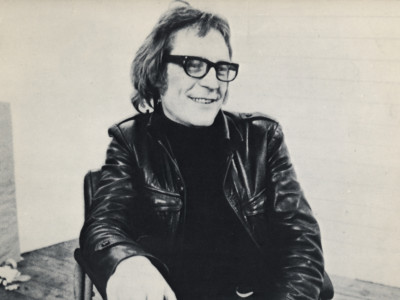

This month the RA celebrates Jasper Johns as one of America’s greatest living artists – here art historian Barbara Rose explores the complex transformations of objects and images throughout his work.

From the Autumn 2017 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

On a trip to Japan in the spring of 1964, Jasper Johns took a photograph of himself in a Tokyo photo booth. He had first become acquainted with Japanese culture and traditions, important to him throughout his life, when he had served in Japan during the Korean War as a young soldier. In Japan, ordinary activities like wrapping a package, preparing tea or arranging flowers demand the same ritualistic attention and precision as high art, which appears to have impressed him. On this trip, he was returning as a 34-year-old tourist. The cheap, mechanically produced photograph, surrounded by stencilled letters spelling out the primary colours, was printed on porcelain dinner plates. Johns incorporated them into twin paintings titled Souvenir and Souvenir 2 that he made in a studio in Tokyo during this two-month trip.

Souvenir is an encaustic painting; Souvenir 2 is an oil. Both include a flashlight attached vertically to the right edge of the canvas pointing up towards a rear-view mirror angled downwards, presumably to reflect a non-existent beam of light from the flashlight directed at a wooden ledge that supports the upright plate. Significantly, all the familiar objects are deprived of their practical functions; instead they are assigned a purely formal role as three-dimensional elements in a basically geometric assemblage composition. As real objects they are useless. The flashlight normally powered by an electronic battery is dead. The mirror reflects nothing visible to the viewer from its oblique angle. It is, however, significant that its original function is to look backwards.

Souvenir, 1964

Souvenir II, 1964

The plate in Souvenir 2 rests against the back of a stretched canvas glued to the surface, so that the viewer can only guess what, if anything, appears on the obverse. No image can be seen on the canvas sealed from view, which serves only to raise the viewer’s curiosity about the front of the canvas that is not visible. Nobody can eat from the vertically-sited plate, which in life would serve food, but in art equates looking with eating. Like the first Souvenir, the works that first brought Johns fame – a 1955 painting of the US flag and two paintings of targets – were painted in encaustic, an ancient tradition requiring heating wax and brushing it on evenly as one would frost a cake. Johns is known to be an excellent cook with an interest in food. Perhaps one reason he was drawn to encaustic as a medium was because it was like cooking. In any event, throughout his work there are constant analogies between seeing and eating, creating parallels between taste and sight. Serving his image on a plate suggests the artist expects to be devoured by acquisitive diners. The expressionless portrait that stoically meets our gaze, of a photograph of the artist’s face printed on a plate, suggests a pun, perhaps on his name, since the most famous head on a platter is that of St John the Baptist, the inspiration for the Baptist religion in which Southerner Jasper Johns was raised.

In Souvenir, the original shadowy version in encaustic, the photograph and stencilled lettering on the plate are black and white. In Souvenir 2, the oil, both photograph and stencilled words are seen in colour; the title Souvenir, appears in the lower centre in handwritten script. This is unusually personal for Johns, who normally uses standard stencilled letters to spell out words and even his signature on paintings. Johns subsequently made four drawings and two lithographs based on the encaustic Souvenir, and three drawings and a lithograph inspired by Souvenir 2. Using a painting as a point of departure for finished drawings and prints is typical of the manner in which he transforms objects into images. The process of complication and manipulation of this metamorphosis, rather than any chronological stylistic progression, is the distinctive characteristic of his evolution as an artist.

The twinned Souvenir paintings and the prints and drawings they breed are Johns’ only self-portraits. However, one can argue that Johns’ entire oeuvre is in fact a cumulative self-portrait extended over a long and fruitful lifetime. It is probably no coincidence that the title evokes not a noun, but the French verb se souvenir, which means "to remember" and has nothing to do with tourism. Beginning with these early self-portraits that memorialise his two-month sojourn in Tokyo in the spring of 1964, Johns turned from obdurate objects like a flag or a target to associations of images informed not by the present but by the past. Executed at that moment Dante called "the middle of the journey of our life", which is also roughly the age, perhaps not coincidentally, that Christ was crucified, the two versions of Souvenir are not only the portrait of the artist as a young man, but also a preview of his modus operandi, in which objects are transformed into images through various forms of reproduction, allowing them to be deconstructed, reordered and grafted on to other surfaces, as well as displaced into a variety of contexts that alter their meaning in surprising combinations and juxtapositions.

Jasper Johns does not want to be understood too quickly.

Barbara Rose

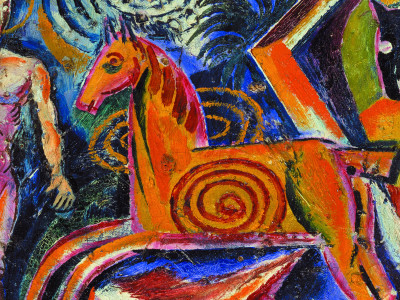

There are many ways of looking at Johns’ work, which is intentional on his part. Like the writer André Gide, author of The Immoralist (1902) and The Counterfeiters (1925), Johns does not want to be understood too quickly. One way we can understand the entire trajectory of his extensive oeuvre is as a single overlapping narrative in which the images are like characters that appear, disappear and reappear in another context, altering their function and identity. This transformation from object to image is particularly striking in the complex works of the early 1980s based on trompe l’oeil precedents, especially that of the picture within the picture, which included 18th-century paintings that inventoried aristocratic picture galleries, as well as the genre of the baroque quodlibet, a pictorial inventory of objects and personal memorabilia tacked to studio walls.

It is within this tradition, which inspired American still-life painters like John F. Peto and William Harnett, that we may comprehend Johns’ lifelong interest in optical illusions. Take, for example, the contents of the 1983 painting Ventriloquist, which references multiple printed images. It contains a representation of the American flag in colours opposed to the original, and a lithograph by Barnett Newman that Johns owns, reversed in a mirror image as it would have looked on the original stone. The theme of the picture within a picture used by Johns in the early ’80s was often employed by Degas to acknowledge his sources and interests. In his ongoing play between reality and illusion, Johns uses rectangular "insets" in numerous works that suggest the cinematic view into another scene used by Alfred Hitchcock in Rear Window (1954).

Objects Johns collected, as well images from previous works, flow into and out of the painting, spilling over other works to connect them in an extended sequence that becomes increasingly loaded, complex and frustrating to decipher. There is, for example, the painted hinge and faux tapes attaching the flag suggesting the illusion of real objects, and the wicker hamper and bathtub fixtures we know existed in his own home. On the left, there are a variety of conflicting illusions. The frontal, shaded, eccentric pots of ceramicist George Ohr are silhouetted against the flattened outline of a whale based on Barry Moser’s 1979 illustrations of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick.

Ohr’s ceramics float as if in a dream over the flattened body of the outlined whale that is so highly patterned with busy stripes it is impossible to read as a background. The most peculiar images in Ventriloquist, however, are the vestiges of the red, white and blue American flag cut off by the left edge of the painting, suggesting that the rest of the flag is wrapped around the back of the work. Indeed, so much that is depicted is visually contradictory in the space Johns has constructed that figure-to-ground relationships are obviated. The very location and orientation of objects is put into question. Johns is too sophisticated an artist not to realise he is setting up a situation that is not only optically challenging but also conceptually logically inconsistent.

Some of the images in Ventriloquist, including the Newman lithograph, are also present in the two versions of Racing Thoughts, one made in 1983 in encaustic before Ventriloquist, and one in oil, painted after Ventriloquist in 1984. In Racing Thoughts, the image of a pair of yellow pants hanging from a hook has convincingly been likened to Michelangelo’s own flayed hide that he painted on the Sistine ceiling. The same types of spatial contradictions and surface fracturing are found earlier in the 1982 Perilous Night, organised as a diptych made up of two halves that do not match. Perilous Night, which refers not to the Star-Spangled Banner but to the title of a 1944 piano composition by John Cage, also includes images of Newman’s lithographs. Perilous Night includes for the first time images taken from Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece (1512-16), in Colmar, Alsace, which Johns visited around this time.

In these picture-within-picture works, themes and images spill from one to another in a way that recalls the appearances and reappearances of the characters in a roman-fleuve, the stream of consciousness novel, such as Marcel Proust’s seven-volume A la recherche du temps perdu (1913-27). There are a number of significant parallels that link Johns’ oeuvre with that of Proust. For example, in his notes for the 1964 painting Watchman, Johns refers to two different witnesses, the Watchman and the Spy, just as Proust is both the writer as well as the narrator of his rumination. While Proust the narrator recalls his life in retrospect, characters change in age, appearance and social standing as the static traditional society in which he was raised gives way to the fluidity of the social aspirations of a rising class of nouveaux riches capitalists. Thus, Odette de Crécy, the vulgar prostitute, marries elegant man-about-town Charles Swann – the character who is also Proust’s alter ego – and by the end of the last volume has become the Princesse de Guermantes, the great society hostess at the top of the social pyramid.

There are other telling parallels between Johns’ paintings and Proust’s writing. For example, Proust conceives of his great work in the reverie of a dream; Johns insists the image of the flag came to him in a dream. For Proust, the distinction between intellect and feelings has to be overcome, just as Johns cautions himself in his 1964 notebook entries to "beware of the body and the mind. Avoid a polar situation." In order not to separate the mind from the senses, Proust’s character Elstir, a painter possibly based on Cézanne, claims "not to paint the object, but the effect it produces". Johns’ lifelong interest in Cézanne is a reflection perhaps of the way in which the French artist produced hovering, destabilised images that never quite resolve themselves optically into fully three-dimensional depictions of volume.

Proust’s multi-volume masterpiece is now generally considered to be a single novel. Similarly, I believe that all of Johns’ work in the divergent media he has mastered can be considered a single, linked work of art. Understanding his works as a linked sequence, as opposed to individual works constituting a series, permits us to account for the way in which time and its passage become increasingly significant for Johns. There are parallels as well in the way memory inspires both writer and artist. Proust begins to remember the past with the help of the taste and smell of a madeleine that he dips in tea that connects him to his memories, allowing him to reflect and create, and to recall people who are dead, things that are broken and places scattered "like souls, remembering, waiting, hoping, amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unflinchingly, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection." In this connection, I think we must take Johns at his word that he begins with nothing specific in mind and that a random image, something seen while driving for example, may inspire him.

Beware of the body and the mind. Avoid a polar situation.

Jasper Johns

Johns’ involvement with the passage of time – he often works on the same piece over many years, revising, reconsidering and reworking – sets him apart from his contemporaries and links him back to earlier masters, such as Cézanne, whose works he also collects. This orientation towards the past, seen if you will in a rearview mirror, is also typical of Southern writers. One thinks of the characters in the linked sagas of Yoknapatawpha County by the American novelist William Faulkner, who wrote about a society in decline, looking back rather than forwards, whose deepest feelings were of sadness, melancholy, loss of the profound humanity of the agricultural society in which he grew up.

Johns we must remember is intensely Southern even though he left South Carolina as a young man to study art in New York. His sense of the intensity and priority of the past and its rhythms and textures is as profound as that of Faulkner. Like Faulker, he is determined to transmit the fullness of the experience of a life lived in a certain place in a certain time. This ambition is announced early in a newspaper clipping sealed into the surface of the 1955 Target with Four Faces, which refers to "history and biography". These will be his dual themes and the content of the totality of his oeuvre, in which every action is a record of something that has happened in the past and the primary task of the artist is to bear witness to and preserve memory.

For example, the broom, a synecdoche for a paintbrush, in the 1961-62 Fool’s House has already swept the floor and is a record of its past trajectory. It is one of various devices in Johns’ work that trace circular paths, echoing the shape of the original Target paintings. Objects such as wipers and rulers scrape paths to document actions that have taken place in the past. These objects did their literal jobs in early works; in later works they are transformed into mutable images that can act as metaphor or allegory. Images drop out. In the 1961 encaustic and collage Disappearance II corners of the canvas are folded into the centre so that if there is an image, it has disappeared because it is covered over. In other early paintings, such as Good Time Charley (1961), Device (1961-62) and Voice (1964-67), rulers and sticks scrape paint into semicircular blurs, recording a past not only recaptured but rendered fixed in time like bronze baby shoes. Indeed, one can interpret Johns’ casts of flashlights, beer and coffee cans similarly as familiar objects permanently memorialising a moment in time. Eventually these three-dimensional objects would be recalled in two-dimensional prints and drawings.

The transformation of objects into images occurs early in Johns’ career. Indeed, we can say that his original 1955 Flag painting constitutes the first such metamorphosis, since it is not a real flag but a painted representation. The question posed by the identification of the image of an American flag with the entire pictorial field is whether we are looking at an actual flag or a picture of a flag, an image of a flag that depicts an object. This oscillating definition is typical of the course Johns would pursue of flipping back and forth between object and image, and employing illusions that can be read two different ways fighting for priority.

Even in its initial iteration the flag, which has appeared in a variety of guises for decades in Johns’ work, is already a fairly complex riddle because the work shares the characteristics of both object and image, given that as an object it is in actuality flat and unlike its conventional representation its depiction by Johns implies no third dimension. The elaboration of the textured surface as a kind of relief, through the use of layers of newsprint dipped in translucent wax, presents a further complication by introducing sensuous tactility to the instant optical recognition of a familiar image. But it is in fact this insistence on both visual complexity and unsettling conceptual reversals that distinguishes Johns’ work from that of any other contemporary artist.

As his work evolves, his over-determined images migrate, assuming unstable and changing identities. Two specifically extended sequences of imagery merit consideration in this context of a free-floating consciousness: the complex illusionism and overloaded, over-determined iconography of the Decoy sequence; and the seemingly abstract crosshatch motif, which is used to befuddle the mind in its spatial contradictions, use of chiaroscuro and implied perspective against itself.

In paintings such as Between the Clock and the Bed (1981), inspired by a late self-portrait of Edvard Munch, the crosshatch pattern becomes an image itself, reminding the viewer of how images are made in prints and drawings. Elsewhere Johns uses images from his own prints, inserting them in paintings of the crosshatch motif.

Like everything in Johns’ vocabulary of images, the crosshatch motif has multiple sources, but most specifically it is the means by which volume is indicated in traditional etchings and engravings. Gradually images such as these evolve until their meaning strays farther and farther from the object or experience that originally inspired them. Moreover, this process of distancing corresponds to the gradual degeneration of images as they are reproduced, before the invention of digital reproduction permitted their permanent stabilisation. In the seemingly abstract patterns of Johns’ crosshatch works the image is distilled into no more than the deconstruction of the process by which it is made.

Printing is the primary means by which Johns transforms objects into images. Often this requires an intermediate step of photography. For Johns, printing is an intimate activity, to the extent that he imprinted parts of his own body in sequences of works such as Diver and Skin. He made his first prints in 1960, under the tutelage of Tatyana Grosman, a European printmaker who had set up Universal Limited Art Editions, a printmaking workshop in West Islip, New York, where Johns continued to work for decades. Both the Decoy sequence and the crosshatch works are inspired by the symbiosis of painting and printmaking that Johns learnt to use to immense creative advantage, permitting him both to continue exploring sequential overlapping imagery, as well as to create new types of spatial constructions.

In translating objects into images through reproductive techniques, Johns takes advantage of the mechanical processes he has learned from progressive proofs in the print studio. As he learns new printmaking techniques, he uses them to extend the range of his paintings. In the late 1960s, he made his first silkscreens, a print process in which pigment is pushed through a mesh screen to adhere to the paper below, which suggested new ways of elaborating surfaces and extended his range as a colourist.

In 1970 Grosman acquired an offset lithographic press normally used for commercial purposes. The upright new mechanical press allowed the rapid proofing of subsequent states of an image, leading to the increasingly complex overlay of many layers of proofed states. This was important in producing the sequence of images involved in the two paintings titled Decoy (1971). The source for the sequence was a photographic reproduction of the 1966 painting Passage II.

Passage I, 1966

Passage II, 1966

Like Watchman and According to What (1964), Passage II is festooned with the cast of a human leg bent at the knee. All three paintings have a ghoulish quality that may subconsciously evoke the activity of brutal serial killers. In this connection we should note that in 1962, Johns visited London’s Madame Tussaud’s with its chamber of horrors, which apparently inspired him to cast a human leg to use in Watchman in 1964, in the first of his anatomical butcherings of bodies into fragments. Earlier, in Target with Plaster Casts (1955), Johns had cast body parts and painted them bright artificial colours. Now he wanted a more realistic image of flesh covered by skin. Watchman, a vertical work, would be followed in 1964 by the horizontal According to What, a magisterial indexing of all the forms of optical illusions, inspired by Duchamp’s taxonomy of representation in his last painting, the 1918 Tu m’.

Like the serial killers who often take a hiatus, Johns did not paint the third canvas containing an inverted human leg, Passage II, until 1966. This time the flesh-coloured painted plaster cast is pinioned to the canvas with a large peg through its ankle and attached to the left side of the canvas. Now the familiar stencilled letters are bent back as if receding into an indeterminate viscous painterly space. On the bottom edge, a neon sign with its electrical socket revealed – one of Johns’ few ventures into technology – spells out the word RED. On the top right, two panels – one red, and one yellow that looks as if it can slide under the red – are marked with unidentified residues of paint that suggest they were created by being blotted on top of each other and then reversed in orientation.

Originally a photograph of Passage II was used as the basis of the lithographs titled Passage I, a print with some of the same bright colours as the original painting, and Passage II, a ghost image in white ink on black paper. The purchase of the offset lithography press made it possible for Johns to then recycle this imagery in 1971 into a large vertical print, Decoy, which turned the horizontal imagery of Passage II on its side. This print also contained a predella of six images from Johns’ First Etching Second State (1967–69).

Johns then made two paintings after the print Decoy. Returning to the image in another lithograph, Decoy II in 1971–73, he reworked the same stone and 18 plates as the original print, adding an another seven plates that made the image even more rich, elaborate and complex. Eventually 19 separate printing elements were used in Decoy, and 26 in Decoy II. All the colour plates were hand drawn as the artist transferred imagery from one work to another.

Originally the hand-fed offset press was bought by Grosman for proofing only. Now it had become the means to create Johns’ most extended series of overlapping imagery, which was modified, altered, revised and recycled in a series of works that resulted in a print becoming the source for a painting. In his 2007 essay Painting Bitten by A Man, Jeffrey Weiss wrote: "Uniquely, Johns’ procedures incorporate the corporeal: the body as an instrument: the painting as body; the drawing as skin." Weiss hints that this process is actually one of self-cannibalisation, in which the artist "eats" or ingests his own imagery. And indeed, we have seen how transforming a painting into prints and then feeding the lithographic image of Decoy back into two paintings cannibalises previous works. Now the painting is no longer literally bitten in an impulsive, sudden act of violent hunger; it is savoured as haute cuisine in a complex combination of textures that require time to be relished and discipline to be prepared.

One meaning of the title Decoy is its reference to the wooden ducks used to fool real ducks into landing and consequently being shot by hunters. In Johns’ game of illusion versus reality, the depicted versus the actual, the decoy is a fake duck. Or put another way, the printed image of a human leg, now hung from the upper right corner of Decoy, can be visually interpreted as dead game hung from a hook, a typical trompe l’oeil subject.

This flipping of an unstable image back and forth into two opposing configurations is found in the popular drawing of the duck-rabbit, an ambiguous figure the brain can interpret as either a rabbit or as a duck that was published in 1960 by E.H. Gombrich in Art and Illusion, a book Johns owns. According to Gombrich, "We remember the rabbit when we see the duck, but we cannot experience both at the same time." The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, whose views have also influenced Johns, was also fascinated by the ambiguity of the duck-rabbit. This unresolvable visual instability is precisely what interested the artist whose mind had turned increasingly to the paradoxical, visual, mental and intellectual contradictions that refused resolution. As already remarked, the direction of Johns’ work is always towards increased complexity and decreased legibility, if by legibility one understands easy and clear definitions.

As the images become more enigmatic, the surfaces become more opaque and elaborate, more impenetrable and less ingratiating. Among Johns’ more disquieting images is that of Montez Singing (1989-90) in which the skin of a face stretched as if detached from the skull, the eyes now staring out of corners. Skin, a subject he has treated in the past, has become the ground on which objects are depicted, raising the question of foreground and background that is the bedrock of pictorial depiction. In the later crosshatch paintings, the space he pictures is that of an impossible world in which partial and perverse perspective and chiaroscuro, originally used to create pictorial illusions, are now enlisted to contradict themselves. Ultimately the field is so littered with images that are discontinuous and mutually contradictory that they verge on incoherence and stay in place only because we believe in the permanence of their geometric confines.

Typical of this dissolution of the background into a discontinuous fragmented surface is the 2010 print Fragment of a Letter, in which the artist draws images of a hand gesturing in sign language as the ground on which other images are depicted. In other works, stick figures meme the mariner’s message for S.O.S., which is now a voiceless cry. What is pictured is what cannot be said. This is the point at which language fails, when both artist and critic become silent. In the words of Wittgenstein, "Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent." At this point both artist and critic are equally deaf and dumb.

Perhaps Johns’ objective is to bring the viewer to the point of muteness, to silence criticism by overwhelming its capacity to analyse. Indeed, with so many conflicting illusions and spatial paradoxes, the mind ultimately boggles under the weight of excess information. For example, we are always finding out new facts about Johns. The 2007 exhibition, Jasper Johns: Gray, which contained exclusively grisaille versions of his works, revealed that over the course of his career the artist has had a doppelganger lurking in the shadows, a twin who is moody, melancholy and obsessed with death. These grey works as it turns out are often the twins of brightly coloured pieces, their dark opposites suggesting another world on the other side of a mirror. The concept of the evil and dangerous doppelganger was popularised by Dostoevsky in the The Double, the story of a meek, introverted government clerk who goes mad because he keeps encountering his aggressive, extroverted double who wishes to inhabit his persona.

On a lithograph that contains the same portrait printed on a ceramic plate in Souvenir and Souvenir 2, Johns had scrawled "dish", hinting also at use of the word to describe someone as attractive. But the expression on the face of the photograph is hardly that of self-satisfaction. Labelling the dour self-portrait as a "dish" was more likely an act of ironic self-deprecation. Indeed, Johns has often criticised himself, saying at times that he was not a great colourist or an accomplished draftsman. This is not the portrait of the artist as a successful statesman or diplomat like Rubens, or even as a rakish bohemian like Picasso. It is the portrait of an artist who is deeply self-critical, if not self-rejective, who looks if anything not smug but terrified.

In the dark series of grey works, death constantly lurks. In the series Tantric Detail (1980-81), skulls repeatedly appear as the exuberance of the youth is replaced by the contemplation of death. T.S. Eliot’s description of the playwright Webster – "much possessed by death/And saw the skull beneath the skin" – might describe Johns as well. In Skin (1975), a large work on paper, Johns imprints his own face and torso. Can we not help but wonder if this body, which is that of an artist, is a corpse like Gatsby floating face down in his West Egg swimming pool?

In the course of Johns’ work, there is no progress but there is evolution, change, redefinition, dissolution, ultimately a fading away and decathecting of the original memory as it is transferred and grafted, translated and faded out, until it is drained of any emotional significance or personal feeling. The book, sealed with encaustic in the 1957 object Book, becomes open in Foirades, (1976-2017), a series of etchings made to illustrate five short stories by Samuel Beckett and based on fragments from the disturbing four-part painting Untitled (1972), which includes fake body parts – hands, feet, legs, male buttocks, a female torso – scattered to resemble scenes of carnage. By the time these disturbing images are reconfigured and recycled in a continuous sequence of prints, their identity is so denatured and generalised we can hardly recognise them as human. And although it is true the painting was made at the height of the Vietnam War, Johns has cautioned against giving any political meaning to his work, even his American flag.

So what are we to make of the meaning of Johns’ deadened, silenced objects, contradictory optical illusions that will not remain fixed, casts and images of human body parts, and paradoxical spaces constructed from the remnants of pictorial representation? Obviously Johns, like the fox in Pinocchio, actively tempts the critic to see. But to see what? The answer must be whatever is already in one’s mind. Johns’ friend Susan Sontag wrote an essay titled Against Interpretation. But is it possible to look at the artist’s images without interpreting them, since they are expressly intended to evoke associations in the viewer? No, I don’t think so. On the other hand, each spectator will inevitably have their own subjective interpretation of Johns’ imagery based on personal experience, and their own dreams, memories and impulses. These subjective interpretations provoked by Johns’ use of increasingly overloaded, charged imagery, which he seems to use the way a director uses "stage business" to keep things moving, may also be the artist’s strategy to keep us from noticing what he is actually up to on a more serious level than storytelling iconography.

The relationship between illusion and reality is the consistent concern that connects all of Johns’ works. He has said that the thread connecting his paintings is defined by the space he creates. How he constructs and interprets that artificial illusion is the storyline of his art. The space he creates through a variety of devices, including reproduction, is shifting and inconsistent like the amorphous space of a dream. The possibility that life itself is a dream is fundamental to both Shakespeare as well as the Buddhist concept of life as a dream. If the picture the artist is representing is that of consciousness itself, then the relationship between illusion and reality, the dream and its contents, must remain unresolvable.

In his most recent works light begins to play a decisive role. It is not the reflected light of the Old Masters, but the illumination from within, the light that also makes the paintings of Barnett Newman so remarkable. It is as if Johns the young sceptic and literal materialist now aspires to the blinding epiphany of the central figure of the transcendent and Christ who rises after death, which is the central image of the Isenheim Altarpiece that inspires many of Johns’ later works. Newman of course is known for his involvement with the concept of humanistic heroism. The New York School were members of what Americans call "the greatest generation". They believed their efforts were heroic. But what could constitute heroism in today’s fractured, fragmented, technology-dominated global world threatened with extinction because of human greed, brutality and ignorance?

As Walter Benjamin observed in his key 1935 essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, technological progress inevitably destroys the "aura" that defines the unique work of art. Could it be, then, that one form of heroism is the restoration of the unique aura of the handmade, finely crafted, individual work of art in the age of technological "progress" and democratic multiplicity? To use the techniques and processes of printmaking, which is fundamentally a craft based on handmade reproduction that opposes the recording of reality in photography, then to resurrect painting as a living, rather than a dying, art form, is at this point nothing less than a heroic task. We have moved from the existential Age of Anxiety to the Age of Instability. Johns’ acceptance of instability as a permanent feature of contemporary experience may also be construed as a heroic stance, both painful and uncomfortable, although inevitable in order to correspond to our shifting moment.

I recall talking to Johns about the body parts Géricault brought home from the morgue to study. Johns said he preferred Leonardo because the Renaissance master dealt with the whole corpse. However, what he admired most about Leonardo, he said, was that he could contemplate and draw the deluge that could end the world without his hand shaking. The mastery of Johns’ recent works proves that at the age of 87 his hand does not shake, no matter what willpower and endurance it may take to keep it still.

Barbara Rose is an art historian and curator who has written extensively on Johns work in essays and catalogues.

Jasper Johns: ‘Something Resembling Truth’ is in the Main Galleries at the RA from 23 September to 10 December.

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door.

Why not join the club?

Related articles

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024

10 RA Schools stories through the centuries

16 May 2024

In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

1 May 2024