A quick interpretation of Cornelia Parker's PsychoBarn

By Sam Jacob

Published on 15 October 2018

With Cornelia Parker’s Hitchcock-inspired barn in the Royal Academy’s courtyard, Sam Jacob takes a look at the psychological, architectural and social layers of this imposing installation.

From the autumn 2018 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

At times of great crisis the world itself seems to lose its footing. Things that seemed solid are suddenly revealed as provisional, their glues and mortars crumbling. “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold,” wrote Yeats in the aftermath of the First World War. But a crisis of political, national, personal dimension – even a world war – is just a moment in time. A snapshot of a vast chronology whose only constant is change at scales of history, geology and cosmology. Solidity is an illusion. There never was a centre. Everything flows. We, as bodies and psyches, are caught in this endless state of change.

This material, formal and psychic transformation is often at the heart of Cornelia Parker RA’s work. Things are held between one state and another – in Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View (1991, below), for example, a shed was blown up, then kept in suspended animation, its fragments hanging from the gallery ceiling.

Parker’s Transitional Object (PsychoBarn) stands in the courtyard of Burlington House from September, having first been shown on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2016 (cover image). “Transitional object” is a term borrowed from developmental psychology describing things like comfort blankets that children adopt as mother-substitutes, as props to test reality.

This artwork brings no comfort though. It is a thing as big and as apparently real as architecture itself. The kind of building that is supposed to give us certainty and foundation, a house. But Parker’s house refuses to do this. Behind its façade of American colonial domesticity is a complex testing of levels of reality. It is built using materials reclaimed from an archetypal American red barn, carefully dismantled then re-made in the image of the house from Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 film Psycho (which itself was a studio lot reinterpretation of an Edward Hopper painting. One thing becomes another in an act of reinvention, as image and form pass from one media to the next.

The Psycho house is a building freighted with its own psychological issues. Home to Norman Bates and his multiple personalities, its architecture has been put on the couch by the philosopher Slavoj Žižek, who suggests that each floor represents a part of Bates’ Freudian make-up: basement as id, ground floor as ego and first floor as superego.

Parker’s barn/house is equally multilayered. And its arrival at Burlington House after its installation at the Met adds to the complexity. A remake of a resurrection of a thing that was only a media apparition in the first place. A vision of archetypical America seen through the double vision of an English film director, then a British artist. An architecture that itself was a hybrid of European architectural elements and styles deployed to legitimise colonial power through half-remembered European nostalgia remade in the heart of a Britain whose own sense of identity, shape and place in the world is in a state of extreme flux, and that is itself heading into an officially titled transitional state.

Sam Jacob is an architect, curator and Professor of Architecture at the University of Illinois.

Cornelia Parker: Transitional Object (PsychoBarn), Annenberg Courtyard, Royal Academy of Arts, 24 Sep–March 2019.

Related articles

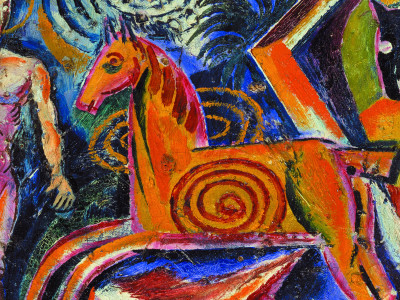

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024

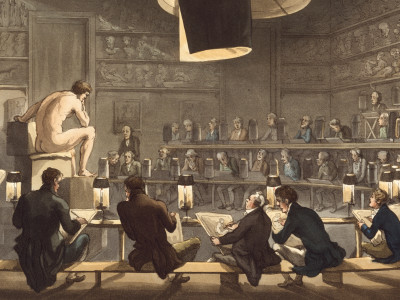

10 RA Schools stories through the centuries

16 May 2024

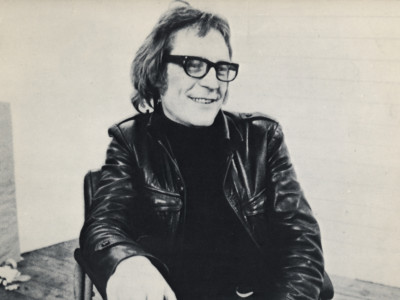

In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

1 May 2024