A designer collection: Cath Kidston on the art in her life

By Martin Gayford

Published on 14 March 2017

With prints on her walls by Calder, Klee and Keith Haring, Cath Kidston has long been an avid collector, and the London Original Print Fair has been the designer’s hunting ground. Martin Gayford went to see the works adorning her Gloucestershire home.

From the Spring 2017 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

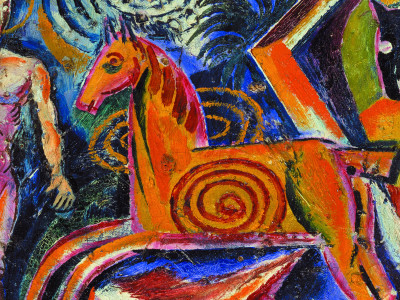

"I’m one of those awful people who likes accruing, who likes gathering things," announces Cath Kidston as she shows me around her Gloucestershire house. "There’s a sea of prints, a lot of stuff. It’s mad!" Indeed, the high stairwell in front of us is covered with an eclectic art-historical array. A Paul Klee is in the mix, and so is an orange crucifixion by John Piper, as well as Mickey Mouse reinterpreted by Damien Hirst in terms of his trademark dots. "I’ve had a thing for Mickey Mouse since I was young," Kidston explains. "This has got energy and it’s fun."

The whole effect of the print wall could be an illustration of Lucian Freud’s dictum that in the end nothing goes with anything, "it’s your taste that puts things together". In this case, of course, the taste is Kidston’s: the same eye and sensibility that directed the hugely successful business that bears her name.

Her own surroundings are visibly related to that familiar look, which could be classified as traditional/contemporary, or "Romantic Modern" in Alexandra Harris’s phrase – or as Kidston herself modestly described her first retail outlet, a "glorified junk shop". Her own interiors depend on extrovert colours, ebullient patterns and assembling all manner of diverse things – and that’s true of the art on the walls too. She is, after all, someone who has built an enormously successful career out of interiors. After working for interior designer Nicky Haslam for a while, she set up a design business with a friend before eventually opening her first shop in 1993.

The house itself is classically English – old, stone-built, at the end of a sweeping drive. On entering one is greeted by a couple of friendly dogs (she is known to be a dog person, as well as a flower person, and both are represented in her designs).

After a tour, we sit down in a cheery sitting-room. It is full of trifles unconsidered – at least by others – which she begins by listing. "Paintings by my great aunt, things from boot sales and a flea market in New York. That little embroidery came from a house clearance in Stroud."

The added ingredient here, not so evident in the chain of shops she founded – now ubiquitous in Britain and spreading to China – is a touch of abstraction. Sharing the walls with the embroidery found in Stroud, for example, is a beautiful Alexander Calder: almost a medley of geometric forms, but not quite because a seal can clearly be discerned, balancing a ball on its nose.

Calder, it turns out, is a longstanding favourite with Kidston. "I’d love to have a Calder mobile if I could. When I was 18 or 19 I went to Venice and was completely bowled over by the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, which introduced me to artists like Calder and that modernist age. The contrast of her gallery with the rest of Venice is an amazing thing."

That sense of old juxtaposed with new is evidently something she enjoys. Another quality Kidston emphasises is visual punch: "clean, strong pieces of art work", which is why she is drawn to printmaking media. "What I like about prints is that there’s often a crispness. The older I get the more I appreciate more graphic things. That’s where it’s coming from. I am a floral person, but I like very graphic flowers."

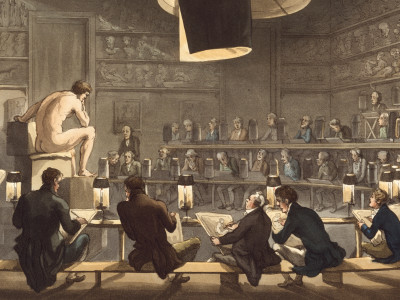

This is a preference that can clearly be seen in the textiles and house furnishings for which she is famous. "For a long time I’ve worked with very traditional wallpaper factories here in England who do 'surface print'”, a method, invented in 1839 and using inked rollers, which produces a beautifully soft effect. "That kind of wallpaper printing is extraordinary. It’s probably the closest experience I’ve had in my business to fine art."

Kidston regrets that many artists do not turn their hands to design these days, as plenty did in past decades. (I agree.) "People like Edward Bawden and Graham Sutherland designed fabrics in the 1920s and '30s and after the War it was quite a thing." She enjoyed the recent Sonia Delaunay exhibition at Tate Modern, and has some of Delaunay’s repeat textile prints.

After I left school I began to work straight away, doing shop jobs, and as soon as I had any spare cash I spent it on collecting pictures.

Cath Kidston

Over the years, starting from fairly conventional beginnings, Kidston’s artistic affections have evolved. "Gradually my taste has gone more and more abstract. My dad loved collecting pictures, and I have some very visual recollections from my childhood, but I don’t think I actually began to collect until I started to earn some money. After I left school I began to work straight away, doing shop jobs, and as soon as I had any spare cash I spent it on collecting pictures. In those days my choices were much more traditional. I went for 18th-century French prints and Hogarth’s Marriage à la Mode, that kind of thing, and I bought Laura Knight drawings, which were really cheap then.

"Once I got a flat in Hammersmith, I really began collecting. I started off with a load of old ’50s flower prints and sets of topographical garden views. I remember framing them. I’ve always been interested in the frame and the picture together: the combination."

"It’s probably in the past 15 or 20 years that I’ve become much more interested in abstract things, starting off when we moved house in 2001. A move is a time to think freshly about things, and that’s when I really began to get more interested in 20th-century and then contemporary work."

The type of print Kidston goes for is bold and – frequently – vividly coloured. A little Ellsworth Kelly Hon RA, layering primary colours, hangs above a joyful pink and yellow paper collage by Terry Frost RA. Primary colour is even more piercing in one of Kelly’s characteristically curved works on the stairwell. This love of bright tones draws Kidston to certain graphic media more than others. Lithography, for example, evidently appeals to her more than etching, a medium which lends itself to subtle networks of line rather than clear, punchy forms. "There’s a strength and a clarity you get from printing on paper that’s fantastic. I like linocuts for that reason." Last year, Kidston co-curated an exhibition of linocuts by contemporary artists at the Watts Gallery, Compton.

Her choices are instinctive rather than programmatic. She is not the kind of collector who selects an area – Expressionist woodcuts, say – and systematically explores it. On the contrary: "Although over the years I’ve come to recognise certain artists, on the whole I don’t buy for an artist’s name. It’s actually a matter of falling in love with a picture, buying on impulse," she declares.

"I like going to exhibitions with an open mind and seeing what there is, so visiting the London Original Print Fair at the RA is one of the occasions I absolutely love – going in thinking, 'Goodness knows what I might find'. Over the years I’ve bought different things there – a red-and-white Louise Bourgeois, for example, and a beautiful print by Gerhard Richter, which I haven’t found anywhere to hang yet. I never buy thinking of where something will go; I get it, then have to fathom out what to do with it."

Each room in her house is a composition in itself, a careful arrangement of this and that. "It’s like doing a jigsaw puzzle. There’s a bit of a gap on the staircase wall for instance that I’m trying to find something to fill. Pretty well any creative decision I make is based on gut feeling – it always has been like that."

What I like about prints is that there’s often a crispness. The older I get the more I appreciate more graphic things

Cath Kidston

Although the spaces in the house have a consistent atmosphere, there are changes in mood from one room to the next. "The sitting-room we use a lot in the winter," Kidston explains. "It’s a cosy place to sit and watch telly so I wanted it to be warm. It’s filled with stuff we’ve had for years, a real mixture that’s built up." In an old coach-house in the garden, on the other hand, there is a feeling which borders on minimalist.

"We go over there in the summer, so I wanted it light and airy." On the walls are three spacious prints in line, alone: two of Donald Judd’s trademark boxes, and an Ellsworth Kelly – again – this time one of his austerely honed studies of plant forms. "I love that Kelly!" Kidston exclaims, "It’s edited down to nothing."

The idea of editing – concentration, reduction – comes up repeatedly in Kidston’s explanations of what she likes, and why she likes it. When I quote David Hockney RA’s view that a desirable feature in drawing and print media is "economy of means", she enthusiastically agrees. Indeed for her, increasingly, it seems, the more economical the better. But there is also an emotional connection between the diverse items on her walls. "Most of the things I’ve chosen," she muses, "have some sort of joy to them". That’s the engaging aspect of the Cath Kidston look.

The London Original Print Fair is in the Main Galleries at the Royal Academy from 4–7 May 2017

Martin Gayford is the art critic for the Spectator.

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

Related articles

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024

10 RA Schools stories through the centuries

16 May 2024

In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

1 May 2024