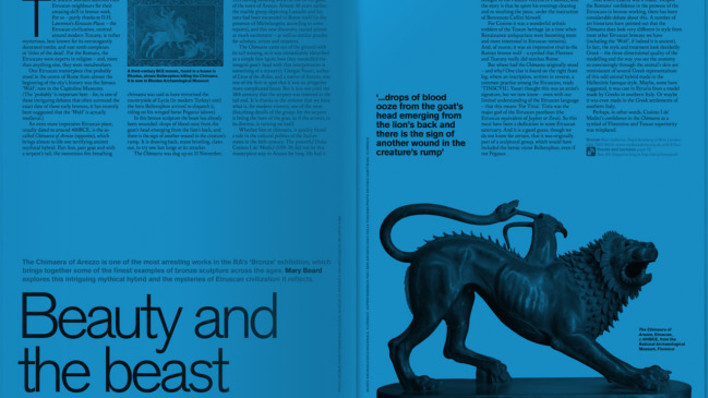

Hélène Binet’s otherworldly photographs

By Fiona Maddocks

Published on 13 October 2021

As Hélène Binet’s enigmatic photographs of buildings go on show at the RA, Fiona Maddocks asks the artist about the meeting between light and line, and mood and memory in her works.

Fiona Maddocks writes for The Observer. Her latest book is Music for Life (Faber & Faber).

To enter Hélène Binet’s world is to turn aside from urban bustle and embrace quietude, in slow time. The Swiss-French artist, who grew up in Italy but has long been based in London, is a photographer beloved of architects. Her subject is buildings but not as you might expect to see them. That wall or pavement in close-up, framed with her distinctive imagination, could be any time, any place.

Binet is fascinated by detail, texture, space and shadow at the point of abstraction. Via her impeccable, hand-finished prints, usually but not always in black and white, we travel to places outside time. Her magical images evoke memories and dreams, conjuring intense responses to structures we have never properly visited or fully observed.

Born in 1959 in Sorengo, Switzerland, Binet has lived in the same converted industrial building in north London, with her architect husband Raoul Bunschoten, a professor at the Berlin Technical University, and their two children (now grown up), since 1992.

Hidden away behind an unpromising fence in a residential street, the pink-washed building is almost invisible behind Virginia creeper, and has an air of a sleeping castle of medieval romance.

Binet’s studio, high-ceilinged, full of filing cabinets and boxes, occupies the first floor. Raoul works below, and they live above. With its troughs and large, plastic bottles of chemicals, her all-important darkroom, off the main studio, is like a small lab.

She collaborates closely on every print with Dirk Lellau, a photo and image editor in Germany who has a background in architecture. “Dirk and I work on everything. When you see a beautiful print, it’s an important collaboration. Before Covid-19 I would go back and forth to Germany. Now we have to manage via computer.”

Hélène Binet in her studio , 2021

Hélène Binet considers photographic prints in her studio, 2021

Portrait of Hélène Binet, June 2021

Thanks to her big-hearted landlords, she has been able to resist the siren call of lucrative commercial work. “It has meant I have been able to do the work I love.” Her photographs, as Binet herself readily attests, do not show off a building’s features or report its shape, size or purpose. It would be wrong to suggest she is intentionally obscure – to meet her is to know that would not interest her – but there is nevertheless a haunting enigma about her work.

Is that a picture of an ancient temple or a modern skyscraper? A Hawksmoor church in London, Le Corbusier’s La Tourette monastery in France or the Jantar Mantar observatory in India? Who knows. Yet she labels her work factually with the architect’s name and the title of the project. It’s not about keeping secrets or leaving us guessing, but about ways of seeing.

There are many professional photographers who can capture a building’s entity brilliantly, even more so with the latest high-tech methods, including the all-seeing camera drone. That’s a different mission, and not one for Binet. Her list of collaborators, however, numbers some of the greatest names in contemporary architecture: among them Zaha Hadid RA, Daniel Libeskind Hon RA, Peter Zumthor Hon RA.

Why is her work, with its deep shadows and geometry of light, so vital to these world-class architects? We can find our own answers in an intimate exhibition of 90 photographs from across Hélène Binet’s career, running at the Royal Academy this autumn and winter.

The show’s title, Light Lines, is a play on words that Binet enjoys. “Light, the key component of my work, and light as in “not heavy”. Lines – well of course lines belong to the architecture world and I too compose my images with lines.”

Her attachment to analogue processes, which require infinite patience and employ methods that belong to a fading world, has continued unabated. “I’m not a co-ordinated, fast person. I need time to reflect. I am slow.” She laughs, yet she means what she says. She uses a large format 4 x 5 Arca Swiss camera with tripod, Kodak and Ilford 4 x 5 film, and Ilford multigrade paper.

The camera has two separate moveable parts, linked by flexible bellows. With the lens at the front and viewing glass at the back, it provides great control of depth and perspective. She may only take one, at most two, shots – worlds away from the now universal habit of snapping a ticker tape of poses on a smartphone.

Binet never crops a shot. Never? “Perhaps very rarely, if something happened – a person walked by, or their shadow clipped the corner – just as I took the picture, which might have taken hours to set up.” Nor do her pictures feature people. “That would turn them into narratives. You have to enter my photos, and sense the space. To have a person there would get in the way.”

One photographer she names as an inspiration is Lucien Hervé, Le Corbusier’s photographer. “I never met him, but his work helped me to see the full potential of what photography could do.”

Softly spoken, warm, reflective, Binet has a clear but never dogmatic sense of what she’s attempting: “I photograph space. Or, better, I frame space. I try to figure out what space means for a blind person, namely many strong experiences: smell, touch, temperature, as well as all the more obvious things. Then I try to put all the ingredients together.

“But when I think about a building, it’s about one thing, a fragment, that can then unfold in the brain as a whole experience.” Meaning what exactly? She continues: “[The American architect] John Hejduk used to say we are “digested” by architecture. We enter a building and we are changed. I am looking for the digestive enzyme! Is it the light, the colour, the size, the sense of peace? Making a building takes years of work. I want to know, what were the visions, the dreams of the architect when they first thought of making that place?”

Growing up in Rome, Binet and her siblings were mainly educated at home by her parents, who encouraged a great sense of freedom, allowing their children to draw or dance or play music all day. “We might visit a church, or see a beautiful painting.” Later, she went to the Istituto Europeo di Design in Rome, where she studied photography and learned technique. Music is a touchstone, a point of reference in her life and work. She learned to play the violin as a child. (As we talk we realise that we sat near each other in the same concert, recently, of Bach’s Goldberg Variations.)

Some of the splashes and cross-hatchings in the textures she photographs might be staves and notes on a manuscript. “It’s as if the architecture is the score and I am a musician interpreting it, making a sound out of silence, working with my dreams, my emotions, exploring details in a particular way, making combinations of shape and shadow. But this is just a metaphor, not an exact parallel.”

Reflecting her love of music, her first job as a photographer was in Geneva’s opera house, the Grand Theatre de Genève, working with dancers and musicians. “I loved being in the theatre, but knew that sort of work wasn’t right for me. I needed something else.”

She found her subject after meeting Raoul and becoming absorbed in architecture, especially through her husband’s links with the Architectural Association in the 1980s, a heady and exciting period for the school. Now Binet’s work is represented in museums and galleries all over the world. In 2019 she had a major show at the Power Station of Art, Shanghai, and is one of the Royal Photographic Society’s Hundred Heroines.

The Royal Academy show, curated by Vicky Richardson, Head of Architecture and Heinz Curator at the RA, will be arranged in sections that reflect varying moods in the work.

The first Binet describes as “poetic, spiritual”, an investigation of an early installation by Libeskind before he began to build, and “something about the play of light” in Le Corbusier’s La Tourette.

The second is about “energy and making” with, especially, a focus on the powerful work of Zaha Hadid – an important figure in Binet’s professional life – as well as the recent concrete adventures of the late German architect Gottfried Böhm.

The third touches on the essentials of architecture: the wall, the ground, the making, ranging from the Lingering Garden of Suzhou in China to the landscaping and pathways of the Acropolis, designed by Dimitris Pikionis in the 1950s.

In conversation Binet frequently returns to memory, and its place in her work. “If you think about your childhood, it’s a room, a staircase, the corner of a garden, a window. If I manage to combine what you see in one of my photographs with a moment, an experience, something in your past, then you engage with what you see.”

Her words bring to mind Proust’s description of time as the fourth dimension of architecture. Binet points to one of the test prints pinned to the studio wall. It shows a small window in a high roof in a church (Gottfried Böhm, Parish Church of St. Gertrude, Cologne, Germany, 2020; above) It’s as if the roof itself is supported by a raft of shadows. “You look, and you put all these thoughts together, and then you begin to doubt and wonder. It’s a special experience in your brain.”

She is right. We’ve all seen that window, in a cellar, an attic, a story, a dream. That’s the alchemy of Binet’s photographs. No wonder architects love her. She gives their buildings character, life, mystery. “I cannot take you there, to that space, but I can give you that memory – and you can create your own private layers of emotion.”

Book tickets to Light Lines: The Architectural Photographs of Hélène Binet

Rediscover the power and presence of architectural wonders by Le Corbusier, Zaha Hadid RA and others through Hélène Binet’s photographic lens.

This exhibition takes place at The Jillian & Arthur M. Sackler Wing of Galleries, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 23 Oct–23 Jan 2022. Supported by The Pictet Group.

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

Related articles

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024

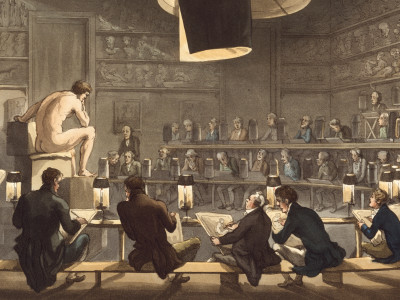

10 RA Schools stories through the centuries

16 May 2024

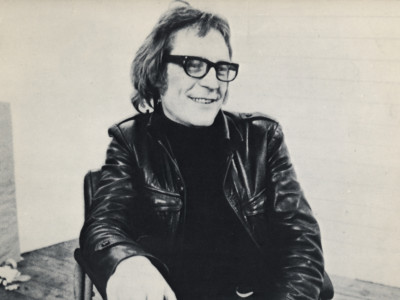

In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

1 May 2024