The story of art in the Russian Revolution

By Martin Sixsmith

Published on 20 December 2016

With a momentous exhibition marking the centenary of the Russian Revolution, Martin Sixsmith charts the course of a pivotal period in art, from euphoric creativity to eventual repression.

From the Winter 2016 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

In his 1957 novel Doctor Zhivago, Boris Pasternak describes his hero’s and, by extension, his own response to the revolutionary fervour of 1917.

"Just think what extraordinary things are happening all around us!" Yuri said. "Such things happen only once in an eternity... Freedom has dropped on us out of the sky!"

Pasternak is talking about more than just politics. Yuri Zhivago is a poet, and his artist’s sensibility (in Russian his name is a play on zhivoy, or "alive") resonates with the visceral changes tearing through his native land. Pasternak’s imagery is febrile, hopeful, anticipating a new beginning and a new life. You can feel the excitement in the Russian air:

Everything was fermenting, growing, rising with the magic yeast of life. The joy of living, like a gentle wind, swept in a broad surge indiscriminately through fields and towns, through walls and fences, through wood and flesh. Not to be overwhelmed by this tidal wave, Yuri went out in the square to listen to the speeches...

What Pasternak is describing, very powerfully, is the birth of love. Zhivago’s outpouring of passion for the revolution coincides with the blossoming of his relationship with Lara. The two merge into the joy that only love can bring.

Pasternak’s reaction wasn’t a one-off. A generation of artists, writers and musicians would greet the perception of bewildering, miraculous freedom bestowed by the revolution with the exhilaration of a nascent love affair. From 1917 up to 1932 – the rough span of the RA’s survey of Russian art – they would experience the whole gamut of emotions that love engenders. The initial, youthful passion that overwhelms caution and sense would lift them to heights of creation. They were inspired, rewarded, fulfilled.

Then came love’s trials, the niggling suspicions, the dawn of mistrust. When doubts surfaced about the purity of their love object, they forced themselves to suppress them. When the faults of the regime became manifest, they looked away.

In the end, the revolution turned against them. Some she consumed in the killing machine of the gulag; others fled, or renounced their art. More than one, some of the best, succumbed to the despair of rejection. Spurned lovers, they found life was no longer worth living and they ended it.

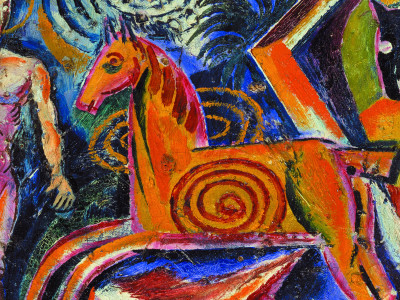

Artistic innovation had smouldered before the revolution. Artists such as Lyubov Popova, Natalia Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov, Alexander Rodchenko and David Burliuk had produced striking avant-garde works earlier than 1917, as had Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich and Marc Chagall. Distracted by having to fight a world war and by domestic unrest, the Tsarist regime had let art slip the leash. The conflict had reduced Russia’s contacts with the West and native talent had taken new directions. Several significant works by Malevich in the exhibition, including Red Square (below) – a red parallelogram, stark and challenging on a white ground – and Dynamic Suprematism Supremus (below), with its vortex of geometric shapes, date from the years before the revolution.

But it was 1917, with its promise of brave new worlds and liberation from the past, that set all the arts aflame. The poets Alexander Blok, Andrei Bely and Sergei Yesenin produced their most important work. Authors such as Mikhail Zoshchenko and Mikhail Bulgakov pushed at the bounds of satire and fantasy. The Futurist poets, chief among them Vladimir Mayakovsky, embraced the revolution while proclaiming the renewal of art. The Poputchiki or Fellow Travellers – writers nominally sympathetic to Bolshevism but nervous about commitment – clashed with the self-described Proletarian writers who brashly claimed the right to speak for the Party. Musical experimentalism broke through the barriers of harmony, overflowed into jazz and created orchestras without conductors. The watchwords were novelty and invention, with pre-revolutionary forms raucously jettisoned from the steamship of modernity.

In the visual arts, Malevich and his followers took painting to new regions in search of abstract geometric purity. The principles of Dynamic Suprematism, proclaimed in his 1926 manifesto The Non-Objective World, ring with the provocative self-confidence of culture in those years. "By Suprematism I mean the supremacy of pure feeling in art... The visual phenomena of the objective world are meaningless; the significant thing is feeling. The appropriate means of representation gives the fullest possible expression to feeling and ignores the familiar appearance of objects. Objective representation... has nothing to do with art. Objectivity is meaningless."

Malevich’s canvases had moved from early realism via a flirtation with Cubism to the ultimate abstraction of shape and colour. His Red Square (1915) is also titled Visual Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions; her "meaningless" visual phenomenon had been distilled into "pure feeling". Like Kandinsky, who had returned to Russia from Germany in 1914, Malevich’s paintings in the decade following the revolution are alive with the rhythmic manipulation of form and space, packed with dynamic shapes that fly precipitously towards the viewer, full of the energy of the age of flight.

Red Square, 1915

This painting was a milestone in Malevich's quest to attain "pure feeling" in his art, distilling the "meaningless" reality of objective phenomena to their inmost essence

Dynamic Suprematism Supremus, c.1915

This painting added rhythmic movement to Malevich's experiments in geometrical abstraction

The Constructivists Vladimir Tatlin, El Lissitzky, Popova and Rodchenko (below) strove to square the circle between the concrete forms of architecture and photography and the values of art for art’s sake. Their structural designs were sharp and angular, a sort of three-dimensional Suprematism. They produced street art celebrating the revolution and denouncing its foes. In 1919 they covered buildings in Vitebsk in vibrant propaganda, with El Lissitzky’s emblematic Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge reducing the complexity of Russia’s civil war to a red triangle piercing a white circle, in a geometric confrontation of good and evil that even the least educated could comprehend. "The streets shall be our brushes," said Mayakovsky, "and the squares our palettes."

Art was spilling into every form of expression. The Bolsheviks were quick to identify the potential of film in influencing the masses, and directors such as Sergei Eisenstein and cinéma-vérité pioneer Dziga Vertov became skilled exponents of politically charged cinema. The newsreel series, Kinodelia (Film Weekly) and Kinopravda (Film Truth), run by Vertov, used Constructivist-inspired intertitles designed by Rodchenko, who also produced their advertising posters.

Space-Force Construction, 1921

The Constructivists applied Suprematist ideals of geometric purity to architecture and design. This painting by Popova heralded three prolific years in textile, typography and stage design before the artist's death from scarlet fever aged 35

Pioneer with Trumpet, 1930

This photograph by Rodchenko combines the political content demanded by the regime (the Pioneers were the Communist youth organisation) with the Constructivist credo that photography and architecture can achieve artistic purity of form

Vertov's documentary on Soviet life experiments with double exposure, fast motion, split screens and jump cuts

The Bolsheviks at first were tolerant, preoccupied with more pressing matters. But by the mid-1920s, the regime was looking disapprovingly at the radicalism and the abstraction, beginning to shape the doctrine that would subjugate all art to the aims of socialism. On 23 April 1932, the Central Committee announced the formation of the Artists’ Union of the USSR, tasked with imposing Socialist Realism as the only acceptable form of artistic expression. From now on, it decreed, art must depict man’s struggle for socialist progress towards a better life. The creative artist must serve the proletariat by being realistic, optimistic and heroic.

The experimentalism that had flourished since the revolution was now deemed un-Soviet. To further the cause of the revolution culture must be comprehensible by the masses; anything more complicated, innovative or original was by definition useless and potentially dangerous. Abstract art didn’t fit the bill. The era of freedom for the avant-garde was over.

With consummately bad timing, a 1932 jubilee retrospective of trends in post-revolutionary art took the celebration of diversity as its keynote. When Artists of the Russian Federation over Fifteen Years 1917–1932 opened at the State Russian Museum in Leningrad, it filled 100 rooms with nearly 2,000 works, ranging from heroic statues and paintings of Lenin and Stalin to the striking paintings of Pavel Filonov, teeming with figures. A whole room was devoted to Malevich’s geometrical canvases and his plaster blocks known as "architectons".

By the time the exhibition was due to move to Moscow in 1933, diversity was a dirty word and many of the contributors were on the Kremlin’s blacklist. Malevich, who had already been interrogated by the NKVD secret police, was far less visible in the show. ("From the first days of the revolution," he told his interrogator, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, "I have been working for the benefit of Soviet art..." and "Art must provide the newest forms... to reflect the social problems of proletarian society.") Neither was there much of Filonov’s work on view, and official disapproval would blight the rest of his life. Even his attempts to make acceptable paintings, including a portrait of Stalin, were rejected. He died from starvation during the siege of Leningrad in 1941.

Socialist Realism spawned much hackery, but also much to admire.

Martin Sixsmith

A great joy of the RA’s exhibition is that it reconstitutes large sections of the original Artists of the Russian Federation show, including the Malevich and Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin rooms almost in their entirety. It presents the abstract and the avant-garde alongside art that overtly champions the regime. If we had tended lazily to assume that the former outstrips the latter in both brilliance of conception and quality of execution, this exhibition might make us think again. Socialist Realism spawned much hackery, but also much to admire.

The most visible face of official art was on the streets, where statues of the revolution’s forerunners and leaders proliferated, ever bigger, ever more heroic. Lenin was portrayed in the throes of revolutionary fervour, his arm extended in a dramatic appeal for commitment to the cause or striding purposefully forward towards the radiant Communist future. In paintings, he is also seen in more intimate settings, working at his desk; hearing petitions from peasants who have appealed to his infallible wisdom; constantly alert, always on guard to protect the Soviet people. Alongside the accomplished realism of artists such as Isaak Brodsky, others brought a quirkier vision. Petrov-Vodkin, who trained as an icon painter, depicts Lenin in his coffin with a glow of preternatural divinity about him (below).

As the Lenin myth grew, so did the intimations of saintliness. Lenin was a holy martyr, presiding Christ-like over the destiny of the nation. A party that had destroyed religion in a deeply Christian country needed something to replace it and holy Lenin, dedicated, ascetic and self-denying, was the answer. Russian peasants maintain a shrine in one corner of their home known as the krasny ugol – the beautiful corner – with a holy icon and a candle. The state was driving out the icons of Christ, replacing them with icons of Lenin.

Portraying Stalin was a tougher ask. Scarred by smallpox, with a withered arm and short of stature, he was not naturally heroic. But just as they turned a blind eye to the faults of the regime, there was no shortage of painters ready to gloss over the imperfections of the leader. Statues made him as tall as the powerfully built Tsar Alexander III and photographs were retouched to disguise his pockmarks. There were artists who persisted in loving the revolution, and some forms of love can make you blind.

It can’t have been easy to look away in the months after 1917. The structures of the state had collapsed under the pressure of world conflict, revolution and civil war. Law and order had broken down, millions were homeless and people were starving in the streets. In the name of War Communism – harsh, enslaving and repressive – Russia was subjected to militarised dictatorship. Challenges to Bolshevik rule, including a failed attempt to assassinate Lenin in August 1918, resulted in the launch of the Red Terror against political opponents and class enemies.

The writer Yevgeny Zamyatin described Petrograd as "a city of icebergs, mammoths and wasteland... where cavemen, swathed in hides and blankets, retreat from cave to cave". People bartered their possessions and family heirlooms for firewood. Dogs and cats disappeared from the streets to be made into "civil war sausage". Even the proletariat was fed up with the Bolsheviks. "Down with Lenin and horsemeat," said the graffiti. "Give us the Tsar and pork!"

Mayakovsky and other leading cultural figures produced billboards and slogans promoting state food stores. My favourite is his witty Nigde kromye kak v Mosselpromye – "You’d have to be dumb not to shop at Mosselprom". But food coupons on display in the exhibition tell another story. Hunger was everywhere. Members of the former middle class, denounced as "bourgeois parasites" and "non-persons" were placed on starvation rations and forced to do cruel, often deadly labour. City streets were filled with war orphans and child thieves. Begging, black-marketeering, crime and prostitution were rife. Bolshevik power was teetering on the brink.

In March 1921, the Bolsheviks were holding their Tenth Party Congress in Petrograd, when 30,000 sailors in the Kronstadt fortress, 50 kilometres away in the Gulf of Finland, rose up in revolt against the regime. The Party was in panic. Trotsky set out with 45,000 troops to march across the ice. Thousands died, but the Kronstadt rebellion was put down and its leaders executed.

It was a warning that Lenin could not ignore. He admitted the Bolsheviks were "barely hanging on". The people were sick of War Communism, weary of hunger and economic meltdown, no longer willing to suffer in the name of some future utopia. Six million people had died in famines across the country. A 70,000-strong peasant army was preparing to challenge Bolshevik power. Military force and mass terror were no longer enough to keep the lid on.

a city of icebergs, mammoths and wasteland… where cavemen, swathed in hides and blankets, retreat from cave to cave...

Yevgeny Zamyatin describing Petrograd

The New Economic Policy (the NEP) was Lenin’s crisis response to this existential challenge. It would loosen the control of the state and reintroduce some elements of private enterprise. Hardline Bolsheviks denounced it as a retreat from socialism, but the NEP, which ran from 1921 to 1929, was effective. Its tolerance of limited personal gain encouraged people to work harder and the peasants to produce more food. And it threw up a new class of speculators similar to today’s oligarchs.

The NEP years saw a rise in the urban population; cities were straining at the seams. The state squeezed workers into smaller and smaller spaces, evicting members of the former bourgeoisie to make way for them. To maximise space, a system of communal living was introduced with multiple families billeted in one apartment, sharing kitchens, bathrooms and even bedrooms. The kommunalka concept was in line with the Bolshevik rejection of bourgeois values such as private property and the nuclear family. But in practice it was a nightmare. Feuds broke out between residents, property was stolen and murders committed. With police informers everywhere, people felt spied on in their own homes. Mistrust was rife; tensions rose.

The grim reality made El Lissitzky’s plans for the perfect apartment look desperately utopian. As a 1927 model reconstructed for the RA exhibition demonstrates, his design is clean, spare and beautiful. It reflects the Constructivists’ insistence that functional houses could also be pure art. But with the economy falling apart and the new leader Stalin consolidating his power through military-industrial projects, such ideals were never going to be taken seriously.

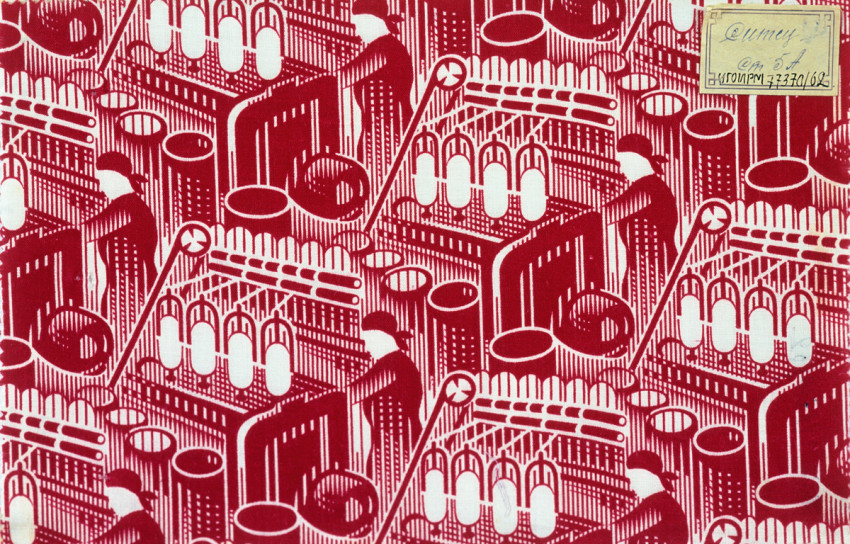

When Stalin launched the first Five Year Plan for industrialisation he said it was a matter of national survival. "We are a hundred years behind the capitalist West," he told Soviet industrialists in 1931. "We must catch up with them in just ten years... or they will crush us!" A continuous working week was introduced, wages cut and harsh penalties introduced for slackers. Millions of labour camp prisoners, and members of the Komsomol (the Young Communist organisation), were used as unpaid labour, their efforts captured in the innovative photography of Arkady Shaikhet and others. Women were nominally accorded equal status with men and were expected to work to the same norms. Alexander Deineka’s paintings of all-female production lines foreshadowed the changed social role that women would play throughout the 70 years of the USSR.

The Five Year Plans set punitive timetables, but at first the Soviet people rose to the challenge. Output more than doubled and gigantic new industrial centres were built from scratch. The River Dnepr was harnessed by a hydroelectric dam that fuelled plants employing half a million people, an achievement celebrated in Isaak Brodsky’s Shock-worker from Dneprostroi (1932), with its towering backlit cranes rising from the earth under the command of the herculean figure of the New Soviet Man. The lightning-fast construction of the blast furnaces of Magnitogorsk in the Urals inspired Time, Forward!, a novel and a feature film about the world record for pouring concrete.

The drive to modernise Soviet industry made machines and technology obligatory subjects for the nation’s culture. The jagged, pounding rhythms of Alexander Mosolov’s overture The Iron Foundry (1926) caught the urgency of the times; Fyodor Gladkov’s Cement (1925) and Nikolai Ostrovsky’s How the Steel was Tempered (1936) became instant bestsellers. Soviet propaganda was creating its own national mythology with the workers themselves as gods. A new breed of superheroes known as shock-workers would spearhead the charge, and the bard of the revolution, Vladimir Mayakovsky, was on hand to deify them. His poem March of the Shock Brigades (1930) is agitprop at its best, marvellously inventive with a powerful, intoxicating message.

Onwards, shock brigades!

From workshops to factories!...

Puff out our collective chest,

And deep into the Russian darkness

Hammer in the lights

Like nails ...

Onwards, with no rest days;

Onwards, with a giant’s steps.

The Five Year Plan

Complete in four!

Now socialism will rise,

Genuine, real, alive.

The successes didn’t last. I remember going with my parents in 1970 to the great Exhibition of the People’s Economic Achievements in Moscow. It seemed then to be the posthumous vindication of Stalin’s vision. Proud guides showed us around extravagant pavilions showcasing the achievements of Soviet industry and technology. But the whole thing was a sham. As we later discovered, the Soviet economy had been hamstrung by a central command system that replaced enterprise and initiative with duplication, inefficiency and waste. "We pretend to work," ran a popular joke, "and they pretend to pay us." The gleaming boasts of success were a façade built on lies and pretence.

A key pledge that helped sweep the Bolsheviks to power was that the land would be given to the peasants. It was a promise they had no intention of keeping. The collectivisation of Soviet agriculture in the years from 1928 to 1940 caused human misery on an unprecedented scale. It unleashed the worst excesses of Communist social engineering and millions died because of it.

Stalin announced that forcing the peasants into large-scale collective farms, sharing labour and equipment would "solve our [food] problems... and remould the peasants’ mentality into the ways of socialism". But for the peasants the land was a sacred inheritance bestowed by God, not the Bolsheviks. They hid or destroyed their crops, and killed their livestock sooner than have it requisitioned. Pavel Filonov’s Collective Farm Worker (1931, below) expresses the sorrow and bewilderment that collectivisation caused.

Disastrous harvests followed, yields plummeted and a two million-tonne shortfall in grain supplies caused waves of famine. The state sent troops to seize peasants’ crops and execute those who resisted. "We must smash the kulaks [peasants who oppose collectivisation]", Stalin declared. "We must eliminate them as a class... We must strike so hard they will never rise again!"

The rhetoric was unhinged because the regime’s very survival was under threat. Soviet culture was told to glorify the shock-troops who were smashing the kulaks and to cover up the misery that existed on the ground. Paintings, poetry, songs and movies overflowed with burgeoning wheat fields and happy peasants on their new collectivised tractors. Malevich, too, complied with the Kremlin’s instruction to return to agriculture as a subject, although his faceless figures of peasants hint at the loss of individuality (Woman with Rake, 1930–32, below).

Collective Farm Worker, 1931

The ambiguous expression in this peasant's eyes seems to capture the pain of Stalin's ruthless collectivisation of agriculture

Woman with Rake, 1930–32

The realism of this work demonstrates how Malevich's art was subjugated to the demands of the Bolsheviks' state

Even the Bolsheviks, with their genius for manipulating the truth, could not pretend that all was rosy. They promised instead that present sacrifices would be rewarded by future happiness in an ideal socialist world. It followed that the task of Socialist Realism was to show the workers what they were working for. Deineka’s sports paintings are resolutely heroic, while Alexander Samokhvalov’s amazons (Girl with Putting Stone, 1933, below) have much in common with those of 1930s Germany. Socialist Realism helped to create the ethos of hope in those years, when first Lenin then Stalin spoke of the utopia that was on the horizon (prompting jokers to point out that the horizon is an imaginary line that recedes into the distance as you approach it).

Not everyone was convinced. Pasternak’s fictional poet Yuri Zhivago falls out of love with the revolution as completely as he fell in love with it, revolted by Bolshevism’s destructive disregard for human values. Real poets and artists became disillusioned, too. Kandinsky and Chagall, both of whom had played public roles in the Bolsheviks’ cultural institutions after 1917, emigrated definitively in the early 1920s. Under political pressure, Malevich adopted a new enigmatic realism that seemed to contradict many of the fundamental values he had striven for (Portrait of Nikolai Punin, 1933, below). In Sergei Yesenin’s poems, you can hear the writer trying to love the new order ("I want to be a poet/And a citizen/In the mighty Soviet state"), but unable to sing the words dictated to him:

I am not your tame canary!

I am a poet!

Not one of your petty hacks.

I may be drunk at times,

But in my eyes

Shines the glorious light of revelation.

The louder Yesenin expressed his doubts, the more his work met with official disfavour. In 1925 he wrote a poem in his own blood and hanged himself in a Leningrad hotel.

Girl with Putting Stone, 1933

This painting is typical of the artist's female figures, depicted as intrepid amazons. It was made a year after the Central Committee declared that art must serve the revolution by being realistic, optimistic and heroic

Portrait of Nikolai Punin, 1933

When compared to the artist's pre-revolution works such as Red Square and Dynamic Suprematism Supremus (both above), this painting suggests a return to realism enforced by the Bolshevik state

Even more shocking was the death of the regime’s own lyricist, Mayakovsky. His poetry is a vigorous, inventive call to arms, a fervent appeal to rise up against the old world and hurry on the advent of the new. But the leaders of the revolution were cultural conservatives. Lenin dismissed Mayakovsky’s work as "nonsense, stupidity, double stupidity and pretentiousness".

By the late 1920s, Mayakovsky was out of love with the revolution, writing plays attacking the philistinism of Soviet society. In April 1930, he shot himself in his Moscow apartment. His suicide note is a poem lamenting the unrequited love that had overwhelmed him:

It’s past one o’clock. You must have gone to bed.

The Milky Way streams silver through the night.

I’m in no hurry; with lightning telegrams

I have no cause to wake or trouble you.

And, as they say, the incident is closed.

Love’s boat has smashed against the daily grind.

Now you and I are quits. Why bother then

To balance mutual sorrows, pains, and hurts...

More writers, poets and artists died in the gulag. They were charged with ludicrous offences such as spying for foreign powers, but in reality their "crimes" were artistic. The work of the great theatre director Vsevolod Meyerhold was experimental and avant-garde. He was opposed to the restrictive dogma of Socialist Realism and made a speech saying so. Tortured by the NKVD, Meyerhold wrote wrenching pleas for clemency from his cell in Moscow’s Lubyanka prison.

They are torturing me. They make me lie face down and beat my spine and feet. Then they beat my feet from above... I howl and weep from the pain. I twist and squeal like a dog. Oh most certainly, death is easier than this. I begin to incriminate myself in the hope I will go quickly to the scaffold.

Meyerhold went to his execution in February 1940, reportedly shouting "Long live Stalin", believing, like many others, that the Father of the Nation could not possibly be aware of the crimes being committed in his name. But Stalin, and Lenin before him, were certainly aware. Art, poetry, music and love meant nothing to the Bolshevik zealots. As the critic Viktor Shklovsky wrote in the 1930s, "Art must move organically, like the heart in the human breast; but they want to regulate it like a train."

"I’m no good at art," Lenin famously said. "Art for me is a just an appendage, and when its use as propaganda – which we need at the moment – is over, we’ll cut it out as useless: snip, snip!"

Martin Sixsmith is a former Moscow correspondent for BBC TV who has written extensively about Russian history and culture. His new book, Ayesha's Gift, is published by Simon & Schuster in 2017

Revolution: Russian Art 1917–1932, Main Galleries, Royal Academy of Arts, 11 February – 17 April 2017.

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

Related articles

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024

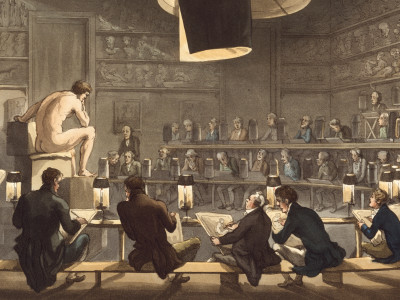

10 RA Schools stories through the centuries

16 May 2024

In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

1 May 2024