The Red Mansion Anniversary Art Prize Exhibition 2020

18 March - 25 March 2020

Weston Studio, RA Schools

Saturday – Thursday 10am – 6pm

Friday 10am – 10pm

Free, no booking required.

Seven heads of the UK’s top art schools present new work made following a residency in China.

Please note: this exhibition was due to open on 18 March 2020, the day after the Royal Academy shut its doors due to the COVID-19 lockdown.

The Red Mansion Foundation was set up 20 years ago to promote cultural exchange between Great Britain and China. Each year the Foundation invites post graduate art students from 7 of the UK’s most prestigious art colleges to travel to China. The works inspired by their travels are then exhibited at the participating colleges. To celebrate its twentieth anniversary The Red Mansion decided to reverse the roles and invite the heads of these art colleges to travel to China during the summer of 2019. The works in this virtual show are the fruits of their journeys to different parts of the country.

Featured artists: Eliza Bonham Carter (Royal Academy Schools), Anthony Gardner (The Ruskin School of Art), David Mabb, (Goldsmiths College), Martin Newth (Chelsea College of Arts), Kieren Reed (Slade School of Fine Art), Alex Schady (Central Saint Martins) and Jo Stockham (Royal College of Art).

Much has happened in the past twenty years when China started to go global. The geopolitical balance has shifted through a Golden Era when we were best friends with Beijing and expectations of each other were high, to today's tense relationship. However challenging the years ahead, it has never been more important to keep the dialogue open and continue to engage. It is our hope that the crystallisation of the artists’ diverse responses to China will contribute to continuing the discourse between East and West.

Nicolette Kwok – Director of the Red Mansion Foundation

The artists reflect on their residency

Back in March the exhibition had been installed, the show was photographed and was ready for the public, however visitors were never able to experience it due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

So in August 2020, the artists met online to talk about their residency in China in 2019 and how these experiences fed into the works they made for the exhibition. What follows here is a selection of quotes from the conversation, paired with images taken during their time in China.

The start of the residency

Jo Stockham: As I was anticipating, I was very overwhelmed by the sheer scale of Beijing. I walk everywhere possible in every city I go to as a way to orientate myself and I was just constantly confused by the scale. I felt like I was in New York sometimes in the sense of the gap between the map and the reality, I couldn’t make sense of it.

Anthony Gardner: Absolutely, what looked like it was only a couple of blocks turned out to be an hour and a half walk.

Alex Schady: Scale was turned on its head because you go to a square and you think it can’t be that big, but then you go and the square just goes on and on. It was amazing.

Eliza Bonham Carter: I’d never seen happier children before in my life. Chinese children just seemed so incredibly happy, I never saw one cry.

I went to the really fabulous Shanghai Museum and it was packed with children and they were just adoring it. Museums in the UK can often feel like a sad place where children have been coerced and they’re bored, but their parents think it's good for them.

Jo Stockham: I noticed lots of kids being with their grandparents in these little parks just hanging out and that really struck me — that sense of community that’s in the street. But that’s the kind of community that’s quite threatened, I think, because they are cleaning out the hutongs and people are being moved out.

They’re becoming really chic, small private museums, coffee shops, gift shops, furniture shops, clothes shops, often with a style between Japanese or Scandinavian that felt really similar to what happened in London, in Shoreditch or Bermondsey.

Anthony Gardner: That wave of gentrification is so powerful, you really feel it in the spaces around the hotel we all stayed in. It was fascinating, and also very attractive, you could understand the sheer attraction of all of that eye candy — the design, the glossy furniture and furnishings, all of that amazing stuff being displayed. But also the massive and very fast transformations that have been happening, most particularly the displacement of families who’ve been in the hutongs for generations, the loss of material and lived histories.

Kieren Reed: As this was my first visit to China I had preconceptions. I was quite worried about the language, the size of Beijing and also about being very much on my own for the duration of my stay. In the past I have travelled more often in a group. But everywhere I went I would find someone who wanted to show me around or take me to a gallery, a museum, an artist's studio, to dinner or to a bar, so sometimes in actuality I felt like I didn't have that space that I craved as well.

Eliza Bonham Carter: I think I was slightly full of trepidation and slightly afraid before I went. And that’s because I thought of China as a kind of monolith, I thought of China as the state and of course as soon as you arrive you’re dealing with the specifics and the individuals and the particularity of the place you are in. And so everything immediately breaks down and you realise how stupid that is to think of a place, a country, monolithicly. But that’s exciting as well, to break out of that into all of those particular experiences.

Alex Schady: Who solved the VPN thing and how quickly? [Virtual private network, a way to access blocked websites in China.]

Jo Stockham: I didn’t take my laptop, which was the first time I'd been separated from it for about 15 years and actually I was really glad about that. (But I did have my phone.)

Martin Newth: The biggest impact for me was on navigation. I totally rely on Google maps, without which I now experience a real loss of spatial awareness. It was a similar experience everywhere I went — not just in the city. I felt I was constantly having to navigate space differently which meant it felt like I was discovering things all the time.

Anthony Gardner: I had prepared VPN but I had also taken a Beijing travel guide from the early twentieth century, so I was travelling around with this clearly extremely outdated travel guide, and I didn't have to worry about maps. And that sense of longer time frames, of something that goes beyond the time of the residency, beyond the time of the VPN as well, recognising everything that has changed and transformed in the course of a hundred years, and what an extraordinary hundred years it has been. So for me that was extraordinary not just pre- and post-VPN but switching off the VPN and going into a well and truly pre-everything set of contexts brought about by a very colonial era travel guide. It was fascinating how little survived yet how much still resonated.

Jo Stockham: I think that sense of deep time is right. I ended up by accident, (because my map was out of date and the Red Gate Gallery had moved), going to the Beijing Ancient Observatory on the first day and that shaped everything for me. I go to the Observatory in Greenwich quite a lot and navigation has been a subject in my work before and so suddenly I was looking at these incredibly sophisticated pieces of technology all made out of bronze. Things that detected earthquakes, compasses and water clocks hugely advanced for their time. These were ransacked by Anglo-French forces and completely destroyed or removed. But some of them had found their way back to the Beijing Ancient Observatory. That sense of time was really confusing and stretched things in really weird ways. Walking through Beijing, I often didn't know what century I was in.

Alex Schady: And there is the time of the tourist, which is also another kind of time. So we are there with our own time frame. We aren’t rushing somewhere, we are ambling towards the next thing that we haven’t quite found, and that presents a very different time.

David Mabb: One of the most revealing things to me was the extent to which it made me aware how Britain has been such a stable society, relative to China. One can look back to the Maoist period, the Cultural Revolution, before that the Civil War with the Kuomintang, the Japanese occupation and Second World War, and even further back to the beginning of the twentieth century and the foreign occupations — including by the British — and the burning down and looting of the treasures of the Chinese dynasties. And you just think, “this has all happened in a hundred years”! This sense of continual convulsion is still there beneath all the neoliberal frenzy of shopping and redevelopment. It’s astounding the pace at which things have changed in China, which is unlike what has happened in Western Europe. It really made me aware of a different kind of temporality and how change there is so condensed: over a single lifetime someone could have lived through several of these phases.

Alex Schady: It’s like space and time have an inverse relationship. Time moves quickly and space is big, or, time moves slowly and space is small.

Eliza Bonham Carter: I spent two weeks on a residency in some buildings that are owned by an agricultural family and there were three generations living there. What has happened in the last century was made very present by their stories. Stories of starvation, the grandmother saw her father shot in front of her, and the kind of shifts that people had to manage in their lives. They described the moment the village was turned into a commune and they weren't allowed to own their own chopsticks or their own spice mix. These were personal stories of momentous historic change.

Martin Newth: I think differences in experiences of time are really interesting. As well as the photographic pieces, I also shot lots of short videos in China and Hong Kong. I haven’t worked out exactly what to do with all these videos yet. But one characteristic that connected them all was the sense of pace at which the country appeared to be moving. It’s not like London at all of course. Even in really busy streets with cars, bikes and pedestrians all moving across each other, there always appeared to be a certain tempo. This is something that came back to me when I saw Eliza's film. That constant flow of the landscape scrolling past. I think there is some connection to Chinese landscape paintings here. I find the way the landscape spatially arranges itself as the train moves recalls or echoes how Chinese landscape paintings are constructed and has parallels with the way many of these works encourage the eye to move across and through the landscape.

Eliza Bonham Carter: In the Shanghai Museum there was a remarkable collection of Chinese landscape painting. For me, that was a really important moment: seeing those works covering many centuries and seeing the shifts in style and approach, the more expressionist moments and the more pared back moments and then that range and economy of mark, a revelation seeing all of these paintings collected together.

Anthony Gardner: I’m just thinking back about grandparents taking grandchildren around — that corresponds entirely to that sense of time and the disjointed condensation of times as well. It was fascinating seeing how generations engage with each other and who’s around the city at particular times of the day as well.

David Mabb: But that’s forced, because both parents are having to work to survive and there's little state childcare and the parents can’t send their children to local schools as the parents don’t have the right permits, so the children have to go to the grandparents. And quite often they are sent to grandparents thousands of miles away while the parents work. The parents then see their children for two weeks a year. So, it's a really broken up family structure because of the economic and political structures that people live under. I thought that was quite brutal.

Anthony Gardner: Yes incredibly, and that ties in again with Eliza's use of the train journey as a mechanism of the train journey connecting these different spaces and times because that's precisely what happens on national days, it's all about those long train journeys.

Alex Schady: It is both brutal and nurturing. It's either a fractured family or an extended family and extended periods with grandparents rather than half an hour here with one parent, then an hour with the other, which is the British equivalent. It's not that one is nurturing and one is brutal, I think it's just two shifting modes. Maybe British kids are all miserable because they're coping with angsty parents who are flinging them from one place to another between jobs.

Making work in China

Martin Newth: I set out with a set of plans and (sort of) ended up doing what I had planned. The work certainly adapted to the circumstances and the experience of actually being in China, but I went prepared with a large-format field camera and sheets of pre-cut photographic paper. One of the things that I was very interested in was the performance of making work. Both in terms of the performance of the trip itself and the performance of re-looking, re-documenting and re-imaging these landscapes which have such a rich and significant history of being painted and photographed.

Depiction of the places I visited plays such a central role in the creation of cultural and national identity. I wanted my work to have a kind of echo of all the other depictions of these landscapes. One of the things I found so fascinating was the sense of change. Wherever I went, even in ancient landscapes, and certainly in the cities, there was a sense of flux. I am really interested in this feeling of change and constant construction — and the relationship between construction of identity and construction of buildings, roads and railways.

Alex Schady: One of the things that troubled me in advance of going to China was the idea of going somewhere, for two weeks in my case, and having to respond to that experience without making crass generalisations, not just grabbing something and thinking its OK to make work out of it. How to navigate this becomes quite tricky — how to navigate the cultural exchange without becoming crass appropriation...

What I thought I was going to make completely changed overnight! I got there and was like, "what I thought I was making, no way, forget it, rethink!" What I ended up doing was making work in the hotel bedroom and that was the space that I could work in because somehow my relationship to the hotel bedroom with the TV and the bed and whatever was somehow a way of working that allowed me to have an experience. The subjectivity was so clear that it couldn't be anything else, so that was my starting point.

David Mabb: I had this idea of what I would do before I arrived, which was to work with local textiles. On my first day I looked at some local textiles and thought, “I don't understand anything I’m looking at; I can't work with this. I don’t understand what it is, what it represents or means or who it’s for”. So, I just dropped the whole project within a few hours of arriving and had to think, “what am I going to do?”. I had to rethink everything because it was very clear that what I thought I was going to do wasn't going to work.

Kieren Reed: I separated the making and the thinking. I couldn’t physically make. I couldn't get tools, I couldn’t get materials. I was told about a great place to get artists materials, so I got the tube there, walked for miles and arrived to find the whole block had gone.

So instead I really thought about materiality, haptics, touch. This relates to my work already, but I could concentrate on the ideas and the thinking rather than the practicalities. I was fascinated by the rocks, minerals, stones and the environment around me. I thought about these in terms of glacial erratics and alluvial flows.

So I ended up documenting everything. Touching, holding and really listening as I explored the city. I suppose I started thinking about some of the things I speak to my students about — what you can do when you don’t have a proper place to make work. How to document and look at what's around you and what is interesting in this exact moment right now.

Anthony Gardner: One of the challenges for me was that I had my arm broken in a massive accident and had had the cast removed the day before the flight so all my expectations had to change completely. Even the idea that I would be doing research, having discussions with curators, all that fell away and that remarkable openness and thinking about others. Kieren, what you were saying about thinking about students, that was exactly where I turned and that impacted the work I end up making.

So that feeling of what comes out of a residency and what doesn't, should you be making work or can it be a thinking space of possibility and projection, all that fed into the exhibition itself in many senses for me. In many ways it was quite transformative in that I shifted from being first and foremost a writer to having to think about different kinds of practices, about making an artwork for the first time in years. And as a consequence I was reminded that art making is really hard! So much harder than writing! My appreciation of what our students work towards and experience (especially our international students, coming to the UK for the first time in their lives in some cases) rose exponentially, and that was largely because of my time in China.

David Mabb: Every day during my stay in Beijing in June 2019 I searched for Chairman Mao. In different places across the city I found portraits, photographs, paintings, sculptures and quotes. I had myself, the tourist, photographed in front of each. These photographs have been pasted over the lead story and photograph from that day’s China Daily, an English language newspaper owned by the Publicity Department of the Communist Party of China. Under each photograph a quote from Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book replaces what would have been the caption. The other photographs from the front and back pages of the newspaper have had different coloured Post-it notes stuck over them, a material trace of the Lennon Walls from Hong Kong where daily protests were taking place during this period but of which there was no coverage in the China Daily. The work is presented in twelve panels, each representing one day spent in Beijing. The display of the newspapers evokes the newspaper walls of the Chinese Cultural Revolution.

Eliza Bonham Carter, Somewhere Between Shanghai and Chengu, 2019. MP4 with sound, 4 hours 30 mins. Courtesy of the artist. "I had two principles: the first was that I wouldn’t bring any materials and so I would work with any materials I could find there, and the other was that I would work digitally which I’ve never done before. In the end I presented what is effectively a documentary film, a film of a long train journey I took from Shanghai across China to Yunnan on the western border. In some ways that means that I did exactly what I planned to, but inevitably what I got isn’t what I expected."

Anthony Gardner, With Meitong Chen and Huw Hallam, I Am A Revolutionary (Apologies to Carey Young), 2020. MP4 with sound, 3mins 45. Courtesy of the artist and collaborators.

Anthony Gardner: In the early 2000s, and still today, I adored Carey Young’s 2001 video performance, *I am a Revolutionary. The set-up is simple. Carey stands in an empty corporate office, in front of three tall glass panels that look out onto yet more offices, a kind of corporate void. Beside her, a corporate speech guru teaches her how to say two lines in the most persuasive, or most enticing, or most authoritative way possible. “My name is Carey Young”, she says. “I am a revolutionary”.

Over and over she speaks the lines, softly, then declaratively, now quickly, now with pauses, the repetitions emphasising yet potentially hollowing out the claims that both art and the artist are revolutionary, avant-garde, perhaps even political in a world (or at least a London art world) bloated with images and constant communication.I wonder what it would be like to translate those lines to the context of today, nearly 20 years after Carey did. I wonder what it would sound like in a language I don’t speak. I ask Meitong to help me.

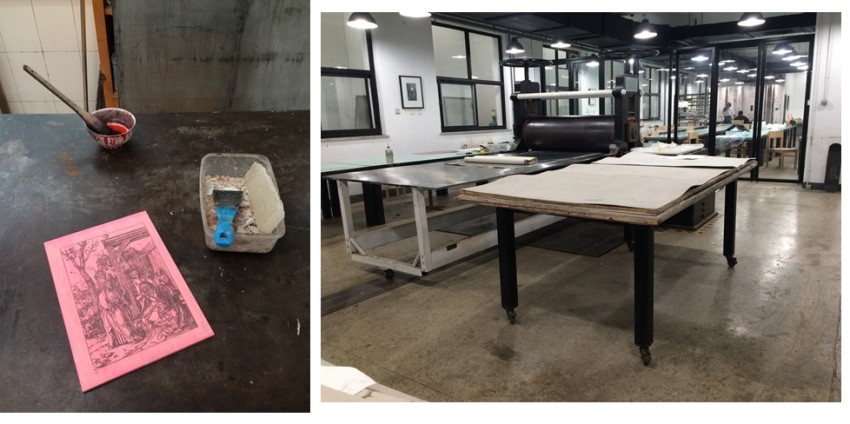

Installing the exhibition at the RA

Jo Stockham: I developed a ritual of looking at the China Daily News every day, it was delivered to the hotel room and obviously David I both use that in our work, in a sense directly, cutting and pasting it. But that did change my perception and I used the language tips, analytics of Confucius column in my work and there was also a version of Time Out, Beijing that’s for an English-speaking audience and that was full of surprising things, articles on the Spanish empire in south China, and an abandoned Canadian Village, but then adverts and awards for clubs and theatre companies, interviews with artists film directors, entrepreneurs.

I've never felt so much like a tourist because I very rarely stay in hotels so I felt really like "I don't know how I’m going to make any work out of this at all". But it was a research trip where I took a lot of photographs and read associated books. I make work slowly and it was only by re-looking at the photos that the work emerged. In Beijing, I was guided by my ex-students and I felt I was learning so much every day and being bombarded with new sensations, acutely aware that this is how it must feel for students arriving in London for the first time.

Day 12, Monday July 1, 2019. “Construction workers take a break outside the Museum of Chinese History in Tiananmen Square. They are in the process of taking down the huge portrait of Mao seen in the scaffolding behind them. The removal of the ubiquitous portraits was aimed at ending the personality cult of Mao, Beijing, 1981.” Photograph by Liu Heung Shing, Star Gallery, 798 Art District, Beijing.

Each panel: 0.71 x 0.56m. Installed 6 x 2 panels: 4.31m x 1.13m. Digital prints, newspaper, Post-it notes and PVA on canvas, 2019-20. Courtesy the artist.

Kieren Reed: Normality is constructed is a modular artwork that incorporates made and found elements within an assembled form. Component pieces are brought together making reference to each other and generating interactions between objects. The selection refers to material and ideas developed whilst in Beijing. Particular reflections have included, the weight of the hand, industry, luck and the number 8, waste, geology – natural, eroded and artificial, smell and sensuality.

Martin Newth: One of the things I was exploring was how you navigate the work in the physical space of the gallery. I wanted to explore a correlation between the construction of the images and the installation of the work as a construction. I was interested in the way a viewer’s encounter with the work might feel like a kind of performance, where your physical movement around the work constructs an experience of looking at the work. The use of the temporary fence material, normally used on building sites, and the painted rock support, were intended to emphasise this aspect of the work.

We all installed our pieces for visitors to encounter physically, but the work could only ever be experienced via documentation. It’s interesting to think about how we might have shifted what we were doing if we had known that people would have been viewing our work on screen rather than in the gallery space.

Martin Newth: From my experience of looking round the show as it was being installed it was striking how many of the works were stressing their own materiality, emphasising the physical relationship between the viewer and the work.

I was struck by Alex Schady's work, with a TV screen on the floor with a glittery boulder on top of it. It felt almost like a kind of affront on the screen as a mode of communication. I find this fascinating to think about now, having gone through four months of screen-based communication with one another.

Alex Schady, With translation by Sizou Chen,

18 Minutes of Crying in my Hotel Room, 2020.

Mixed media installation. Video edited in August 2020 for display online.

Courtesy of the artist.

Looking forward: British art schools and China

David Mabb: Last time I went to China, I found the academies heavily controlled. But on this trip to Beijing, I was taken to a project space in a block of flats which was operating outside of what seemed permissible, where even the next-door neighbours didn’t know what was going on — and deliberately so.

But, over a number of years, the space had been putting on very ambitious exhibitions for a very small audience, who were interested in what contemporary art might be. They were publishing catalogues, having seminars, and every month they would do a new show. I thought, “wow this is amazing”; but it was all basically underground — no permits, no permissions.

All this was happening and it was so removed from my experiences of going into the academies and the tight control of what art was in these teaching institutions. For me the big disconnect was between the teaching structure in the academies and both the commercial and the alternative, artist-run art worlds. It was actually quite remarkable compared with say Britain or America where public and private, state and non-state are very integrated.

Anthony Gardner: Building off that, what I was really struck by was seeing how some of the material that would have been underground even 20 or 30 years ago — I’m thinking about the 1989 China/Avant-Garde show, things like that — had become core features of a contemporary Chinese art history now located within museums. The Red Brick Art museum had this celebration of the 1989 show, which was infamous for being closed down by Chinese officials because one of the artists shot a bullet at her work. Here it was, now, being celebrated as this high point in recent contemporary art practice which was a really fascinating twisting or inversion of what that history had been…

I’m also thinking of some of the amazing shows at the Inside-Out Art Museum in the outskirts of Beijing, and the new and radical material presented there. I think, David, you’re right that the galleries or museums were doing things that were really fascinating and pushing the envelope in many respects and looking at challenging, provocative histories, where maybe the art schools and academies were doing something much more safe.

Martin Newth: It was extremely valuable to experience first-hand the kind of culture shock of visiting China. This really hit home to me when I arrived in Hong Kong. I was really struck by how, in comparison to the towns and cities of mainland China, so much of it felt more familiar — cars driving on the left and red London busses, for example. Experiencing this first-hand really helps reflect on how our Chinese students must feel when they come to study in London.

Alex Schady: The culture shock that I experienced this time was greater than I’ve experienced anywhere else. Just not knowing what anything meant, not knowing what a shop would be until I walked into it, what something in a window represented, not being able to understand anything and to be able to transcribe that feeling onto what our Chinese students might be feeling when they first arrive in London was incredibly useful.

I hadn't quite taken on board quite what that experience would be like and the speed they adapt to that is astonishing. It's important not to underestimate that aspect of their experience.

David Mabb: What I'm trying to get my head around is how we can help students when they first arrive, so it's not such a trauma for them to work out how to function successfully within this new context. One of the things that going to China did help me think about is how the academy system works in China and how the art world works in China. I think we can make postgraduate programmes that can create meaningful and useful transitions between these two very different realities.

Martin Newth: At Chelsea, next academic year we will commit to having a talk about the history and current nature of Chinese art delivered in Chinese (with a translator). I knew pitifully little about Chinese art and it was really great to get to know a bit more about its rich history and legacies by experiencing the art, culture and landscape of the country. It’s imperative that all our students get much better acquainted with all kinds of international art and their histories, and I think it is essential that one of the cultures we give more attention to is the Chinese because of its importance in the way the world is depicted and understood.

I also met with alumni groups in Beijing. I have found that they have always been fantastically well-networked and really value being part of a community who have the shared experience of studying in London. My feeling is that there might be a great appetite amongst our graduates to extend these networks to include others who have studied at different institutions across London.

Kieren Reed: That would benefit us all. It's about global reach, which has the potential to help our students be happier as artists and more successful. I think that's something we can really help each other with and I think it would benefit us all as art schools because it's about that community of practice. There are points where we are competitive and then there are other points where we need to work more closely together. Brexit and Covid are two big examples of needing to connect.

Jo Stockham: I think this trip, meeting with alumni and visiting The Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA), reinforced the need to talk more about pedagogy. To address with all students that we are often coming from really different systems of thinking and making, being really explicit, we rarely used to talk about that. Now we’re trying to find ways to do that, to make spaces to share the incredible cultural histories our students bring with them. And of course our histories are intertwined.

Thinking about reading lists, the decolonisation of the curriculum as well, what does it really mean to work with an international cohort? What does that mean in relation to China, which Chinese theorists, artists, curators are leading the field and who should we be referencing? I think there's a lot to share.

Artist biographies

Eliza Bonham Carter is Curator and Head of the Royal Academy Schools in London, a position she has held since 2006. Bonham Carter studied painting at Ravensbourne College of Art and Design and completed her MA at the Royal College of Art.

Anthony Gardner

Anthony Gardner is Head of the Ruskin School of Art at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of The Queen’s College. His research explores the intersections of contemporary art and politics, with particular emphasis on installation, performance, exhibitions and cultural infrastructures.

David Mabb

David Mabb works with appropriated imagery to rethink the political implications of different aesthetic forms in modern art and design history. Mabb teaches at Goldsmiths, University of London where he is Reader in Art and Programme Co-Director MFA Fine Art.

Martin Newth is an artist and Programme Director of Fine Art at Chelsea College of Arts. He studied at Newcastle University and the Slade School of Art. Primarily using photography, but also video and installation, Newth explores the processes by which works are made and the material properties of photography.

Kieren Reed

Kieren Reed's practice encompasses sculpture, public art, performance and installation, from studies in form to the production of architectural structures. His art is often linked to a process, place or a consideration of a space or situation. He is Director at the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London.

Jo Stockham is Professor and Head of Print, School of Arts and Humanities at the Royal College of Art. Her practice is installation-based, often dealing with the histories of a site, using sculpture, sound projection, found materials and digital technologies.Stockham studied Painting at Falmouth School of Art and holds a Master’s degree in Sculpture from Chelsea School of Art.

Alex Schady

Alex Schady playfully challenges romantic notions of the artist and creativity through sculpture, video and performance. In 1998 Schady co-founded the gallery space Five Years to explore the relationship between programming, curation and practice. He is currently Director of Fine Art at Central St Martins.

The Red Mansion Foundation

The Red Mansion Foundation is a not-for-profit organisation, which promotes artistic exchange between China and the UK. Our mission is to increase knowledge and appreciation of contemporary Chinese art in the UK whilst encouraging understanding.

Weston Studio

This public exhibition space is dedicated to innovative and experimental projects, exhibitions, installations, and interventions; alongside occasional events, readings, and performances presented by Royal Academy Schools students and graduates.

Until it opened to the public in May 2018, the Weston Studio was a working studio occupied by generations of Royal Academy Schools students. Similar studios are still located on either side of the space.

Royal Academy Schools

The Royal Academy Schools offers a 3-year full-time postgraduate programme in contemporary fine art for up to 17 artists each year. The course is aimed at artists who want to develop their practice through exposure to new ideas and constructive critique, dialogue with a diversity of voices and access to specialist workshops.

The Royal Academy was founded ‘to promote the appreciation and understanding of art’, and also its practice. At its heart was the creation of the Royal Academy Schools, a school of art established to set the standard for the training and professionalism of the next generation of artists, to nurture and develop the artists of tomorrow. The ambition of the founding Academicians was to facilitate the transfer of knowledge from one generation of artists to the next and that this should be, 'free to all students who shall be qualified to receive advantage from such studies’ (Royal Academy of Arts Instrument of Foundation 1768) and this remains the case to this day.