Zaha Hadid RA on the influence of Malevich in her work

By Zaha Hadid

Published on 21 July 2014

As a major Malevich show goes on view, Zaha Hadid RA reveals how her use of painting and drawing to develop buildings was inspired by the artist.

From the Summer 2014 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

In 1915 Kazimir Malevich presented his abstract paintings at the ‘0.10’ exhibition in Petrograd (now St Petersburg). It was a revolutionary show that forged entirely new forms of experimentation and expression.

I became interested in these works in the 1970s, when I was a student at the Architectural Association in London. I think the dire economic situation in the West in those years fostered in us similar ambitions to those of early 20th-century Russian artists: we thought to apply radical new ideas to regenerate society.

The 1970s were a critical time of investigation. Although architects had little work, we were very productive with drawings. One result of my interest in Malevich was my decision to employ painting as a design tool. I found the traditional system of architectural drawing to be limiting and was searching for a new means of representation. Studying Malevich allowed me to develop abstraction as an investigative principle.

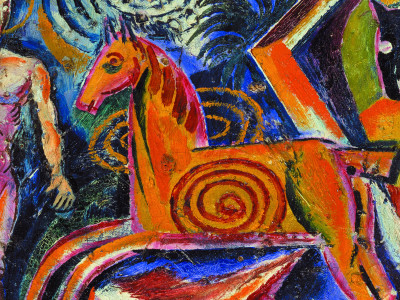

I used painting to develop my proposals for the Peak Leisure Club in Hong Kong (1982-83), a building that was to be based on the landscape, and intended as a new man-made geology or ecology. The design evolved from my earlier projects such as Malevich’s Tektonik (1976-77), my fourth-year project at the AA. The idea was to impose Malevich’s sculpture Architekton Alpha (1920) on an urban context to become architecture. My project imposed it on London’s Hungerford Bridge on the Thames in a series of horizontal layers. My fifth-year thesis, The Museum of the 19th Century (1977-78), also researched ideas about juxtaposition and superimposition. The continuous line with many trajectories on the same surface evolved in my drawings and paintings at this time; I was using different perspectives to develop distortion.

Malevich’s Dissolution of a Plane (1917) represents an important moment. His geometric forms began a conceptual development beyond the planar, becoming forces and energies, leading to ideas about how space itself might be distorted to increase dynamism and complexity without losing continuity. My work explored these ideas through concepts such as explosion, fragmentation, warping and bundling. The ideas of lightness, floating and fluidity in my work all come from this research.

Dissolution of a Plane, 1917

The Peak Blue Slabs, 1982-83

This system of drawing led to new ideas, such as layering drawings over one another – like a form of reverse archaeology – which led to literal translations in the buildings. Vitra Fire Station (1983) in Weil am Rhein, Germany, was key – the drawing became the project, when the lines became volumes.

It took me 20 years to convince people to draw everything in three dimensions, with an army of people trying to draw the most difficult perspectives. Now everyone does 3D on the computer, but I think we have lost some transparency in the process. Through painting and drawing, we can discover so much more than anticipated. It might take 10 years for a 2D sketch to evolve into a workable space, and into a building, but these are the journeys that I think are the most exciting, as they are not predictable.

Malevich is at the Tate Modern, London until 26 October 2014.

Related articles

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024

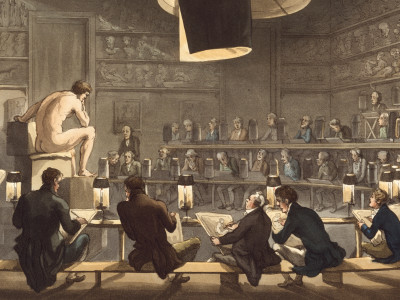

10 RA Schools stories through the centuries

16 May 2024

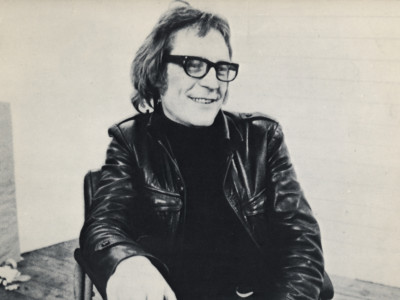

In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

1 May 2024