Are we building too many museums?

By Stella Duffy and Kieran Long

Published on 20 May 2015

Would building more museums help to improve society or be a wasteful luxury? Theatre-maker Stella Duffy and curator Kieran Long go head to head. Read both sides then vote in the poll below.

From the Spring 2015 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

Yes...

We should focus all of our efforts on opening up existing museums to a much wider public, says Stella Duffy.

We don’t need another museum or another gallery because we don’t fully use those that we already have. Additionally, we have far too many city-centre venues. While many buildings purport to be for all, sharing arts and culture with all, they cannot possibly do so from a static base. Not everyone lives in a city, and of those who do, not all live in London, and many of those who do live in London still don’t feel welcome in the moneyed monoliths that are our major arts institutions.

Instead of creating yet more buildings for an elite (if your venue isn’t free to all, if there are still people who do not feel your venue is for them, then yes, it’s for an elite), we need to utilise the spaces we do have properly. Turn our night- empty galleries into dance studios, change foyers into midnight rehearsal spaces, share thousands of offices for free evening classes, or simply offer an hour at a well-lit desk to the would-be writer in the night cleaning team.

Currently, too many of our arts institutions use the school visit as their main form of engagement, but a teenager who does not enjoy school will equate both venue and art form with the schooling they don’t enjoy, and are less likely to ask a parent or guardian to bring them again. Further, if an adult does not feel comfortable in the building, they will not bring their child, and the depressing circle of privileged parents privileging their children continues. Depressing, not least, because it means new blood is not coming into the arts, and the arts are diminished when this happens.

Instead of creating yet more buildings for an elite, we need to utilise the spaces we already have

I was born in a south London council estate and grew up in a small New Zealand town, two hours from the nearest gallery or museum. My family did not regularly engage with formal arts provision, not least because, as products of the pre-Second World War working class, little about arts venues made my parents feel welcome. Not enough has changed. I first visited the RA only ten years ago, taken by a friend who is a Friend. I had walked past the courtyard many times, yet had no idea it was available to me.

The RA is over the road from Fortnum & Mason: how many of their staff regularly use the courtyard, let alone the gallery? How many doing the lowest-paid jobs in galleries and museums feel they own the spaces in which they work? The troubling statistics from the Warwick Commission Report on the future of cultural value tell us that the ‘wealthiest, better educated and least ethnically diverse 8 per cent of the population are most culturally active’. Public engagement must be more than school visits or summer schools for those lucky enough to live near a venue, more than occasional late-night openings. Take art to the people instead. Save the money from a single big new build and create dozens of touring exhibitions, travelling to shopping malls, camping sites, rural villages. Wider access is good for the people and good for future arts.

I have worked in the arts as a writer and theatre-maker for over 30 years, and I know we are still not making ‘arts for all’. So if you must build, make a Fun Palace when you do. I co- founded the Fun Palaces campaign to promote the widest possible engagement with and access to culture for all people in local communities. Ask the plumbers and electricians working on your building what they’d like to learn, hear, view, enjoy. Invite the cleaners to curate. In our Fun Palaces pilot last year, with 138 venues and locations participating across the UK, tens of thousands joined in. Venues that opened their doors to all, found that 70 per cent were visiting for the first time – because the community were invited to curate, to create, their families and neighbours came to see what they had made. For just one day, these organisations attended to their geographic community, and came alive locally. Sharing the arts more fully with everyone might mean we have to open our doors a little wider than is comfortable – it’s a small price for finally achieving arts for all.

Stella Duffy is a writer, theatre-maker and Co-Director of Fun Palaces, a national campaign for greater access for all to the arts. Her story collection Everything is Moving, Everything is Joined is published by Salt (2014).

No...

New museums can bring positive change to the places in which they are built, argues Kieran Long.

While there are still more people going to the British Museum than to Alton Towers, and while in the past year London’s V&A (where I work as a curator) had record visitor numbers (3.6 million), it is difficult to argue that the public’s appetite for museums is sated. People want to come. Whatever else they might be, museums are a primary leisure destination today, especially in cities, and urban populations are set to continue to rise for some while longer.

I believe museums are so popular because they are public in the best sense: they are accessible, not driven by commerce. They empower people with reliable knowledge and have a sense of authenticity and institutional mission that is rare in public life. Museums are often in beautiful or strange buildings. The things in them are not for sale. These are not common attributes in the city these days.

We feel good in places where generations have cared for a collection, where artists, designers, scientists and scholars have been inspired, where social and economic hierarchies are put on hold and cultural ones are in question. Museums are places that are owned by the public, and they are loyal to a different set of values than those of the shopping mall or theme park.

Of course museums do not inherently possess these qualities. We see the results of the National Lottery culture-building boom of the 1990s and 2000s with its many successes, but also plenty of institutions without a mission, with no clear sense of public duty, and with an offer pitched somewhere between didactic educational experience and theme park. Also, too many museums are obsessed with contemporary fine art, and not enough with the crossovers between artistic production and design, digital, architecture, technology, science, anthropology and history.

Museums have a sense of authenticity and institutional mission that is rare in public life

But there is a new model brewing. One of the pioneers has been Grizedale Arts, based on a farm in Coniston, Cumbria. Under Director Adam Sutherland, it has conducted a wide-ranging enquiry on how art can be useful. Its Ruskinian ethos helps the public to make things and even to make money from their work. But Grizedale also collaborates with world-class artists on useful projects – its Liam Gillick- designed library in Coniston is a surreal, but also oddly appropriate thing to find in a small town in Cumbria. At a small scale Grizedale has become a rich, multifaceted institution and an impressive profile in terms of curatorial practice.

Sutherland asks what can art and craft do for the public at a granular, local level, and he takes the answer seriously. Grizedale alumnus Alistair Hudson has just taken over Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art and is set to bring the same sensibility to one of those Lottery-funded buildings that has been struggling for a mission. I await the results with excitement.

At the V&A we are beginning the process of designing a new museum for the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in Stratford, London, as part of a new cultural quarter. We want that new building to reframe for the digital age the Victorian civic ethos of Albertopolis, the cultural area around London’s Exhibition Road that is home to the V&A. When a museum with the V&A’s resources arrives in a borough such as Newham, it has the potential to make a generational shift in aspiration, education and culture in a place that is ready for it.

If we consider the question at the level of individual communities that long for impartial, reliable, civic institutions that aspire to provoke profound artistic, philosophical and political reflections in their audiences, then museums are as essential as bus stops, job centres or town halls to the communities they serve.

Kieran Long is Keeper of the Design, Architecture and Digital Department of the V&A, and was formerly Editor of the Architects’ Journal.

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door.

Why not join the club?

Related articles

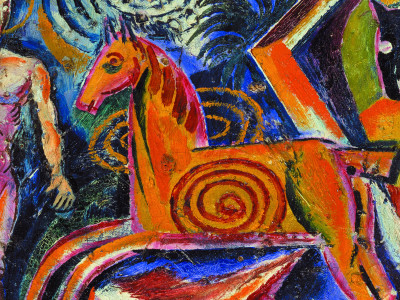

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024

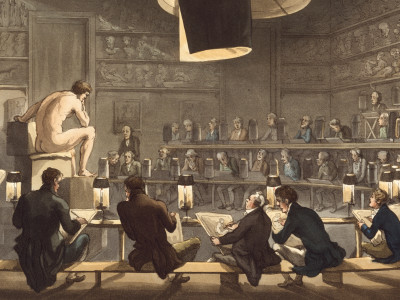

10 RA Schools stories through the centuries

16 May 2024

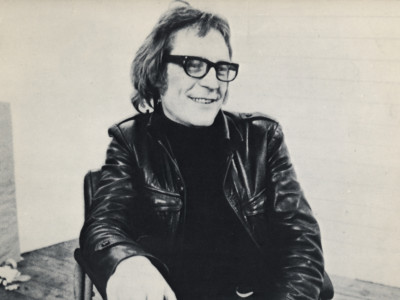

In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

1 May 2024