The Age of Bronze

By Michael Wood

Published on 29 August 2012

Spanning over five millenia, the RA's ambitious survey show places contemporary artists' works alongside works dating back to the Bronze Age.

From the Autumn 2012 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

Outside our office window, across the rooftops, I can see the bell tower of St Bartholomew’s Church with its gilded weather-vane. In the evenings, ringing out over Smithfield, Barts’ bells make that most joyous and comforting of all man-made sounds in the English landscape. Cast in bronze bell metal by a Whitechapel master at the end of the Middle Ages, their peals still delight the ear. Sound across time. And after all, don’t we measure our human ages by metals? After the Age of Stone came the Age of Bronze: that great transformation of human society across the globe from Europe to China. Civilisation came with the working of bronze. In an ancient Greek papyrus fragment, the Titans respond to the first sound from the primeval smithy with this: "It sings! The bronze resounds far and wide! And it sings so loud!"

The RA’s exhibition shows exactly why bronze has captivated us ever since – in its feel, its texture, patina, sheen and colour, its cool aliveness, its longevity.

"Bronze is a unique material for sculpture because it has inspired artists all over the world to speak a richly diverse, but at the same time unexpectedly universal, language," says David Ekserdjian, who has co-curated the show with the RA’s Cecilia Treves. How did it come together? "The aim was simple: to assemble the greatest movable bronzes from across the globe, and in the main that has proved possible," Ekserdjian explains.

Bronzes can be small or large, heavy or light, rough or smooth, conveying the sharpness of a sword blade, the suppleness of human flesh. To see what I mean, look at the swaying, larger than life-size Dancing Satyr from the fourth-century BCE, his neck thrown back in the ecstasy of the dance. It was netted by fisherman in 1998 from the sea bed off Sicily, and some scholars having attributed this stunning work to the famous Greek sculptor Praxiteles.

The oldest artistic medium after stone, wood, bone and shell, bronze has been used in all the cultures of the Old World and Africa – though not, it would seem, in pre-Columbian America. The works in this landmark exhibition come from every important bronze-working tradition. Nothing like it on this global scale has ever been attempted before. It includes examples from the entire history of bronze-making, with works from the great ancient cultures of the Bronze Age all the way to Rodin’s Age of Bronze (1877), Matisse’s Back Reliefs (c.1909-30), Brancusi’s Danaïde (c.1918), Moore’s Helmet Head III (1960) and even Jeff Koons Hon RA’s Basketball (1985).

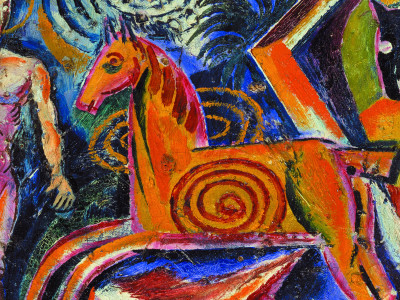

Gathered together in one place, these are works of art you could spend a lifetime hoping to see: exquisite archaic bells and ritual vessels from China; a stunningly regal head from 14th-century Ife in present day Nigeria; a loose-limbed Nepali Goddess Uma, wife of Shiva, from the 11th century. Among the most jaw-dropping exhibits are a three-tonne bronze Laocoön, a two-metre diameter spider by Louise Bourgeois (1996), and one of the least known but most fascinating items, the Chariot of the Sun from Bronze Age Denmark. Discovered in 1902 in a Zealand peat bog, the purpose of this piece is still much debated, but it is likely to have been the focus of a religious ritual in which the sun’s passage across the sky was acted out by priests. This is a lost-wax cast, and the refinement of the decoration on the horse and the disc underlines the extraordinary sophistication of a work from northern Europe at this very early date: coming from the time of the Trojan War, it seems like a relic from some prehistoric version of Star Wars.

This exhibition spans cultures, and is organised not by time or region but by themes: the human figure, the animal world, reliefs and portrait busts, gods, groups, ritual objects, weapons, helmets and shields. It offers the most intriguing juxtapositions, and inspires thought-provoking connections. To take one example: the human figure has been perhaps the single most popular theme for bronze sculpture from ancient Egypt until today. Among some breathtaking pieces on show here are the spectacular, larger-than-life Renaissance statue of St Stephen by Lorenzo Ghiberti (1425-29), created for the church of Orsanmichele, Florence, and a lovely 14th-century bowman from Jebba Island in Nigeria. Seen together, they tell you immediately that humanism was not only the preserve of the Western tradition. Each one positively glows with humanity.

The room containing portrait busts displays more wonders. From Herculaneum there is the fabulously baroque head originally thought to be of the ancient king Tolomeo Apione (154-196CE) with its startling curled spikes of hair, but more recently claimed to be a portrait of an Egyptian princess. From 17th-century Europe come royal sculptor Francesco Fanelli’s haunting Charles I (c.1635) gnawed by the anxieties of power, and Georg Petel’s laurel-crowned King Gustavus Adolphus (1595-1632), the founder of the Swedish empire, who was one of history’s greatest military commanders. Known as the "lion of the North", the king is shown head thrown back, pugnacious and restless; here, more convincingly than in any painting, is the man who swept his world away in Europe’s worst pre-modern war. And alongside these thrilling objects is a real coup: from the 4th-century BCE the stunning portrait bust of Seuthes III (pictured), a contemporary of Alexander the Great, recently discovered in the Valley of the Thracian Kings at Kazanlak in Bulgaria. Here is the man who resisted the Macedonians at the height of their power. Seldom in one space will you find humanity’s cult of rulership more intriguingly juxtaposed.

Another section of the exhibition is devoted to the gods. The enduring qualities of bronze, and its uncanny potential for verisimilitude, have led to its use for religious images for over five millennia, and on show are spellbinding examples, from Ancient Egypt and India, to Classical Greece and Renaissance Italy. Among them are the sixth-century Buddha Shakyamuni from Bihar, standing with his right hand raised in the gesture of reassurance, and the Hindu Shiva Nataraja or Lord of the Dance shown trampling on a demon, a 20th-century version in the style of a 12th-century Chola statue. Each of these works is worth a visit on its own. They offer rich insights into the fundamental commonality of thought and imagination in human culture: our attempts to cross the boundary between the seen and the unseen.

It is safe to say that you will never again see anything like this gathered under one roof. But when you look at the beauty and refinement of the exhibits, don’t forget that these magical things are also the product of industry, of the foundry and the casting shop, of smoke and fire, clay and sand, hammer and chisel. This aspect of the art of bronze is also covered in the RA’s exhibition.

After all, the first bronze-making was a kind of alchemy, as is memorably conjured by Karen Blixen in Out of Africa, where she recalls a typical African forge in the 1920s in the Ngong Hills, the locals crowding around the forge of the caster, whose work had a "mythical force so virile that it appals and melts the women’s hearts; it is straight and unaffected, and tells the truth and nothing but the truth."

Thinking on Blixen’s words, not long ago I had the chance to film a family of traditional bronze casters in south India, whose ancestors created some of the loveliest bronzes in all art, several examples of which are in the RA exhibition, including a delightful Nandi, the faithful bull of Shiva. The casters live and work at Swamimalai near Kumbakonam, a centre for the making of bronze statues and bells for many centuries. Today, they still follow the techniques of the ancient world, in particular the lost wax process from which so many of the pieces in the RA exhibition were created.

To enter the world of the traditional bronze caster is to enter a cramped, hot, smoky realm that is a far cry from the domain of High Art. Behind the shop front, a grimy store room is heaped with old bronze utensils waiting to be melted down, and partly stripped rough casts propped against the walls. In the workshop, amid heaps of slag, tools and broken moulds, are the sand pits where moulds brimming with molten bronze are buried. Here, beauty comes out of barely subdued chaos. How do the artists achieve such minute detail? Hair, jewellery, earrings, clothes? A tiger’s tooth on a necklace? The wrinkles on a god’s fingers? The answer is that the old masters made the close detail in the finest beeswax, modelled onto the mould, not cut later, as is often done these days. In all this everything is handed down: the human form is modelled according to classical proportions laid down in texts. Here the artist has no egotism. When it comes to the gods, artistic self-expression and innovation is not the goal. That, I imagine, was true of the makers of many of the earliest pieces in the exhibition.

Once the sun-hardened mould with the wax image inside it is ready for casting, it is lifted onto a wood fire, covered with cow dung, and left to cook slowly. The wax runs out, leaving the empty mould inside its hardened clay case, and then the mould is buried in sand, and the molten bronze poured in. After 24 hours it is dug out, a shapeless charred lump, and the workers set about it with hammers, until, rather like Michelangelo’s giants pushing out of their prisons of stone, the legs and arms of dancing Shiva or all-seeing Vishnu emerge. One can only say, as Blixen did, that it is magic: "At the forge the hammer sang to you what you wanted to hear, as if it was giving voice to your own heart."

In India this is still a religious art – as of course it was in Shang Dynasty China and Buddhist Japan – and the last stage of the process is a short ceremony in which the priest takes the bronze from the caster and animates it with the divine breath.

Of his art, the Tamil master told me this: "A human life is 70 years. The bronze is metal, but it also has a life. My craft is just to bring it into the world. And this bronze I hope will last thousands of years." That may explain the enduring power of bronze. In an age when the ephemeral is celebrated, and when the superficial has become the substance, to encounter the pristine elegance and beauty of such works, to feel the grandeur of their conception, some of them more than 5,000 years old, is simply spine-tingling.

Bronze is in the Main Galleries, 15 September - 9 December 2012

Michael Wood is a historian, filmmaker and writer, who has made over 100 films.

Enjoyed this article?

"As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door.

Why not join the club?"

Related articles

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024

10 RA Schools stories through the centuries

16 May 2024

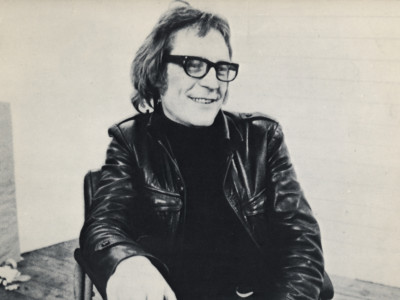

In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

1 May 2024