Should art be more political?

By Bob and Roberta Smith RA and Kelly Grovier

Published on 26 February 2015

Should art have politics at the forefront of its agenda? Artist Bob and Roberta Smith RA and critic Kelly Grovier go head to head.

From the Spring 2015 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

Yes

Artists should make work that speaks out against society's ills, argues Bob and Roberta Smith RA

I know what people mean when they say artists should be "more political". They mean people should address politics more directly in their art.

The times we live in are so horrible, the news so unbearable, that it seems strange that so little contemporary art deals with the shocking imagery of our age. For the RA’s 2014 Summer Exhibition, I transcribed onto canvas an interview between BBC Radio 4 presenter Eddie Mair and Dr David Nott that had discussed the surgeon’s efforts to save lives in Syria. I was trying to say something about the gap between the average Summer Exhibition-goer’s experience of enjoying life and David Nott’s experience of saving life.

But sometimes I think that to draw a lemon or a landscape can be deeply subversive in a time when our Education Secretary Nicky Morgan declares that "choosing the arts in school can hold children back". I believe it has been a terrible time for art education – so much so that I am now standing as an independent candidate against Michael Gove in Surrey Heath – and one could argue that the last thing we should be doing is placing more prescriptive demands on people who call themselves artists. "Let people do their thing," I can hear my inner hippy cry.

But great art is always political. Great art has to say something, and that something is often mind-bending, earth-shaking and epoch-altering. Take, for instance, Goya’s The Horrors of War, Picasso’s Guernica, Louise Bourgeois’ Cell or John Heartfield’s collages that warned of the rise of Nazism. Or Tracey Emin RA’s Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995, her piece where the names of people she had slept with were embroidered on the inside of a tent – the embodiment, in nylon, of the idea that the personal is political. Or J.M.W. Turner RA, who showed us not only dying slaves thrown from ships to drown close to port, but also wives picking through the corpses of their husbands killed on the plains of Waterloo.

Artists need to get in front of politicians and with an eagle eye inspect and depict each expression of mean-mindedness.

Bob and Roberta Smith

At MoMA PS1 in New York last year, I saw a landmark exhibition, Zero Tolerance, curated by the museum’s director Klaus Biesenbach. The show examined the idea that the world’s repressive regimes are cracking down on art for the same reason that New York Mayor Giuliani cracked down on homeless people at the end of the 1990s. The reason? Kill the chicken and you scare the cow. Imprison Ai Weiwei Hon RA and beat up Pussy Riot and you tell wider society that compliance is the only way forward.

I don’t think that in Britain we live in an extreme police state, but we do live in a state of mind that is deadened by the media, where kids are told education is just about getting a job, where few young people can afford to buy somewhere to live and where some kids are brainwashed to think violence is the only way out. For the first time since Mosley in the 1930s, we now have a serious political party that is telling people Britain’s problems stem from outsiders.

This is why art is embracing, indeed must embrace, politics. Call me old fashioned, but I think we have a duty to society not just to buy things we don’t need and borrow money we cannot afford, but also to speak out. We need to treat our politicians with the same zero tolerance of which they are so fond. Artists need to get in front of politicians and with an eagle eye inspect and depict each expression of mean-mindedness. We also must advocate the world we want to live in. It’s not Pussy Riot or Ai Weiwei who are extreme or outrageous, it is the governments who rule over them. To protect our society and make it more democratic, artists’ diverse, angry voices must be celebrated and heard. The Royal Academy and the great public collections are not just art galleries. They are huge repositories of free speech and free thinking.

No

Politics should not dominate art, argues critic Kelly Grovier

Art with an agenda is rarely good art. The only obligation that art bears is to enable its audience to reflect more profoundly on what it means to be here in the world. If one thinks of the most moving examples of political art from the Western tradition – Picasso’s Guernica, say, or David’s The Death of Marat – their success lies less in the particularities of the social conflicts they chronicle than in the timelessness of their comprehension of what in 1950 the American writer William Faulkner called "the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself". These "alone", Faulkner said, are what makes the act of creating "worth the agony and the sweat". What makes Picasso’s and David’s masterpieces moving is precisely that which deepens the countenances of less obviously political works, such as Rothko’s diaphanous veils or the world-weary blossoms of Van Gogh’s sunflowers: the poignant grasp of the contours of human anguish and soulful travail. Goya’s The Third of May, 1808 and Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa are not great works of art because they are political, they are great works of art that happen to be political.

Politics, at best, can only be incidental to the achievement of a great work. At worst, it risks miring an object in the ephemera of transitory context, diminishing the work’s meaning to something didactic and disposable. Insisting that art should be more political is surely as arbitrary as asserting it should be more scientific or philosophical or theological. Such an insistence suggests an impatience with the power of art as art to be significant – that it requires an auxiliary cause to justify and elevate it.

Fortunately, we live in an age of agile artists, adept at deploying politics as an invigorating texture in their works – one that agitates subliminally from beneath without capsizing meaning. Indeed, politics is everywhere in today’s art if we know how to detect and decode it.

Insisting that art should be more political is as arbitrary as asserting it should be more scientific.

Kelly Grovier

In Sean Scully RA’s ongoing series of austere grids, Doric, the quadrate jostle of simple blocks of monochrome may seem at furthest remove from the social frictions of the day. Scully’s title alludes to one of the three ancient orders of classical architecture and the furious purity of form he achieves in his work commemorates Greece’s gifts to global culture, including democracy. Exhibited in 2012, the Doric series unveiled itself at a moment when many in Europe were demanding that Greece be cut off for its alleged fiscal improvidences. Without tethering itself to the fleeting specifics of this clash, Scully’s series embraces timeless and archetypal tensions.

Or take the squeegeed canvases in Gerhard Richter’s Cage series, created for the 2007 Venice Biennale. Though the paintings appear to scrape clean any acknowledgement of the political context against which it was conceived (escalations in violence between Palestine and Israel in 2006), they nevertheless harmonize into a mute symphony of tumult and torment, in which each note of colour is conducted through a tug-of-war between horizontal and vertical scores.

Or, lastly, take the crumpled eloquence of Cornelia Parker RA’s brutal chandelier, Breathless, installed in the V&A in autumn 2001. Comprising 54 brass instruments crushed flat by the machinery used to raise and lower London’s Tower Bridge, the work at once proclaims the end of imperialism while salvaging a tortuous elegance from the debris. Described by Parker as "the last gasp of empire", Breathless aims to crush shut not only an era of colonial arrogance and exploitation but centuries of chauvinism during which any such work by a woman artist would have been accorded little space. What Scully, Richter and Parker intuitively understand is that politics is most powerful when it is an ingredient that vibrates from below the surface, not a perishable varnish that glazes the eye.

Bob and Roberta Smith RA is an artist. Kelly Grovier is a writer.

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

Related articles

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024

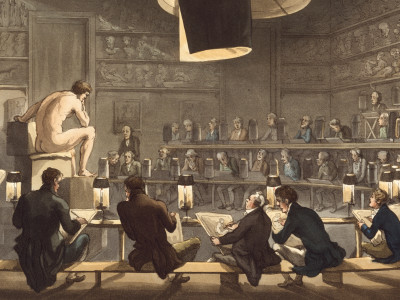

10 RA Schools stories through the centuries

16 May 2024

In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

1 May 2024