Herzog & de Meuron: at home and abroad

By Tim Abrahams

Published on 6 July 2023

From London’s Tate Modern to Beijing’s Bird’s Nest stadium, Herzog & de Meuron’s buildings are world-renowned – yet their biggest impact has been on their home city of Basel, discovers Tim Abrahams as the RA celebrates their extraordinary architecture.

From the Summer 2023 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

The Roche Building 1 is an improbable, elegant, white wedge of a building 41 storeys high, which sails over the pleasant Mittel-European city of Basel. It was the tallest building in Switzerland until last year, when Building 1 lost its elevated position nationally to the 50-storey Building 2, an almost identical white wedge set at a 90-degree angle on the opposite side of the road. From the tops of these towers, the founders of the firm who designed them, Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, can look down and make out the homes where they grew up.

Few architects have had such a large impact on their home city as Herzog & de Meuron. It may be known as an internationally successful architecture practice, but its founders have a fierce pride in Basel, having designed around 40 of its buildings. In addition to the towers, they’ve expanded its major concert hall and built its football stadium, they’ve masterplanned its creative districts, they’ve built its futuristic aluminium-clad exhibition hall, which hosts Art Basel, the world’s pre-eminent art fair. It’s a huge horizontal building with a gross floor area of over 83,000 square metres, which floats out above the streetscape, like an elevated railway station; a piece of modern infrastructure.

Indeed, when it comes to their relationship with Basel, one probably has to step not just out of architectural history but into the realms of French Romantic novels to find parallels: Victor Hugo perhaps. Jacques Herzog though is a man not given to flights of sentimentality. ‘We built the most in the part of the city we grew up in, Kleinbasel. It has a totally new topography, like you couldn’t transform it more… That’s psychologically interesting.’ He smiles. ‘It’s almost as if we are reversing our history.’

Yet with their first retrospective exhibition in nearly 20 years about to open at the RA, some self-reflection is inevitable, even if for Jacques Herzog – the composed, driven spokesperson for the partnership – it is unusual. ‘As an architect you work on projects for such a long time, you often kill your memories of them. It’s like when you have a dream and then you speak about that dream to the first person you meet and it’s like a bubble that evaporates.’ Even so, the possibility that a nexus of his personal and professional lives lies somewhere out on Basel’s Grenzacherstrasse plays on him. ‘It is weird,’ he admits.

Herzog & de Meuron certainly arrived at the perfect place at the perfect time. Jacques and Pierre met in 1956, aged six, at primary school, and although they went different ways for a spell – Jacques to university to read biology and chemistry, and Pierre to do his military service and from thence to study engineering – they both disliked their chosen paths. ‘Talking on the phone, we both decided to do architecture because it was a bit of everything,’ says Herzog. At the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology they studied under the great Italian architect Aldo Rossi. When their final diploma loomed, they opted to do it together and have never really parted since, clocking up almost 50 years of partnership.

Meanwhile the wider region of Basel – which did not experience the post-war boom of, say, Zurich, largely because it was divided between three countries – was ready to expand. With the rapprochements that led to the Schengen Agreement – which Switzerland signed even though it is not an EU member – Basel could resolve the strange inconsistencies of its urban layout. The architects reached maturity just as the city was ready to grow upwards as well as outwards. They have 600 staff members working worldwide today, but it feels as if their first partner from the very beginning was the city of Basel itself.

The exhibition at the RA contains a section of what the practice calls the Kabinett. This is a meticulously indexed archive that has the air of a natural history museum’s backroom. Instead of ibex skulls in boxes though, the archive, consisting of tall wooden vitrines with shelves and sliding doors, contains buildings, or rather the models, plans and ephemera and all manner of different test cases for different materials that go into buildings.

Donald Mak, an associate of the practice, takes me through the serried ranks of vitrines, which display their projects in chronological order, each with their project number displayed. Materials range from samples for concrete panels depicting scenes of German history, made for the Eberswalde Technical School Library in north-east Germany, to prototype blocks of rammed earth for a herb processing centre in Laufen, Switzerland, their seventh project for the herbal sweet manufacturer Ricola.

‘The first row of vitrines represents a span of 158 early projects, when the office was Jacques, Pierre and a small number of staff.’ As we walk Mak pauses at a vitrine, filled with a very familiar shape. ‘Then you have the Tate…’ And here are two models, both made in wood and some acrylic. There is a handsized Tate Modern and a larger sectional model showing the Turbine Hall at 1:200 scale. Beyond this point the amount of space dedicated to each project expands, to match the increased scale of material production that the office underwent to address the step-up that Tate Modern gave them. If Basel was the playground in which Herzog & de Meuron learned, London was where they reached maturity. It scaled their work up massively. Walking through the Kabinett, this transformation is thrown into stark relief. By the time you reach the point where their later extension to Tate Modern, the Switch House, is stored, the production of the office has expanded to eight vitrines worth of material.

If the existence of the Kabinett would suggest that making an exhibition about the practice is easy, Herzog disagrees. ‘Every exhibition is like a project,’ he says. ‘And we always try to make our projects unique in the sense that they are specifically made for a given place, a given time, a given budget.’ They range from the double skin of polycarbonate and glass at London’s Laban Dance Centre, designed in collaboration with artist Michael Craig-Martin RA, that makes the building shine like a jewel amidst the Deptford murk; to the epoch-marking use of massive steel members at the Bird’s Nest stadium in Beijing, designed in collaboration with Ai Weiwei Hon RA; to the strange peaked crown of the Elbphilharmonie concert hall in Hamburg.

It can sometimes feel hard to grasp the common thread through their works, before you consider the idea that their site-specific quality is as much about time as it is place.

‘The Kabinett fulfils another obsession I have, which is putting order into things, and that it does to my highest satisfaction,’ continues Herzog. I try to imagine the orders of orderliness between me and this great Swiss architect and he almost disappears into the clouds. The open nature of the storage, the fact one can see the artefacts (it is not public but scholars and interested parties can apply to access it), is important. ‘Storing and exhibiting and presenting are all terms which are connected to perception and perception is the fundament of creativity.’

Our city is like a kind of sandbox, which, like children, we can play in and imagine things

Jacques Herzog

This appreciation of the primacy of aesthetic perception sets Herzog & de Meuron apart as architects. It was a lesson they learned alongside Rémy Zaugg, an artist who was a kind of extra partner of the practice in the early days and whose death in 2005 hit both Pierre and Jacques hard. (There’s a room dedicated to his typographic paintings in the Kabinett, almost a shrine to his intelligence and his perception.) With Zaugg, they made an urban plan of Basel for the Chamber of Commerce back in 1991, which identified areas where the city could expand. ‘The way we look at cities is much more based on perception than using one style or theory of urban history. I was never interested in that… I was almost aggressively uninterested in it,’ Herzog says, before another rueful smile. ‘As a young practitioner, you have to be a bit stupid and a bit obsessed,’ he adds.

The Kabinett is testimony to this process of looking. Inevitably it owes something to Basel too. The historic nucleus of the city’s exceptional Kunstmuseum was the Amerbach Cabinet, an ensemble of Renaissance art acquired by the city in 1661 and made accessible to the public since. The building in which the Kabinett is housed, designed of course by Herzog & de Meuron, gives something back to the city too. It stands in a corner of Dreispitz, an area in Basel whose masterplan was first drawn up by the practice in 2001 but revisited again recently. This neighbourhood, dominated by a former international customs depot, has been reimagined by the practice as a creative district, home to a university of design, a museum of electronic arts and other cultural buildings. ‘Our city is like a kind of sandbox, which, like children, we can play in and imagine things,’ says Herzog. ‘Eventually these proposals can become true or can trigger other developments or the work of future generations.’

With the first room of the RA show displaying a section of the Kabinett, the second features films, including one by artist duo Bêka & Lemoine on REHAB. This is a rehabilitation hospital in Basel – completed in 2002, and extended in 2020 – for patients with neurological or motor disabilities to recuperate following trauma or surgery. With its wards wrapped around courtyards, unimpeded by doorways, it is a building of quiet sympathy. The ceilings of the patient rooms are graced by bubble skylights. Pierre de Meuron remembered seeing a young man paralysed from a motorcycle accident when they first began designing the building, and he realised how important the ceiling and the sky would become to someone bedbound.

A wonderful building in its own right, it is also the prototype for a much larger project: the Kinderspital in Zurich, which is the subject of the final room of the RA’s exhibition. Nominally this children’s hospital was chosen as an example of the complexity that the practice now has to deal with: the hospital as both a city and a machine. But it also shows a softer side to the practice. Its design is overseen by Christine Binswanger, who joined Herzog & de Meuron in 1991 at the age of 26. Now a senior partner and one of the people who chooses which projects the office goes after, she remembers that there was actually a debate in the office over whether do the REHAB project (it won out over a bank project) before she became its lead architect. She explains what REHAB and Kinderspital share: ‘the horizontality and the orientation inside the structure around courtyards. The way we have tried to integrate nature, the different levels of privacy. The scale and intuitive wayfinding.’

The Kinderspital is of another order to REHAB though. It has ten times the floor space and sits on a site bigger than Windsor Castle. It is a massive project with a huge number of technological and medical requirements. The curators at the RA are showing, among other elements, a large plan of the building. An app that visitors can download to their own devices triggers augmented reality materials, including renderings and photographs developed for the planning and construction of the building. ‘I’d love people who visit the exhibition to leave and say, “Oh, there’s more thinking behind architecture than I thought”,’ says Binswanger.

In addition to Jacques and Pierre, the practice has 15 partners who work across the projects to ensure consistency. ‘Every project has two partners, one who is in charge, and one who knows enough to make qualified comments and criticism,’ explains Binswanger. They explore numerous iterations of every idea for a building, assessing each until they arrive at the best solution, the one that relates best to the overall concept.

Considering this process, I am reminded of a particular smile I have seen on the faces of staff through 20 years of visiting their buildings. It is the grin on the face of Donald Mak when he describes the extraordinarily complex steel work of the Bird’s Nest stadium in Beijing: ‘We added layers to create a certain chaos. But it’s all very – let’s call it – intentional.’ I remember the glee of John O’Mara, the associate who worked on the RCA Battersea, when he noted how they embedded cables deep in the floor of the studios so sculpture students could employ drills without shorting the electrics. And how phlegmatic the partner Robert Hösl was when he explained that an extension to the Küppersmühle Museum in Duisburg had to be scrapped when the steel was found to be substandard, and how the new design, with its beautiful but slightly crazed brickwork, emerged from that. The practice is full of people who take their jobs seriously but not themselves. The wry smile alludes to often fraught decision-making which, once navigated, leads not just to excellence but also a certain ambiguity of meaning. The original concept and the built reality always coexist in the final building.

Herzog & de Meuron’s success is due to this working culture that Jacques and Pierre have created: one which produces a workforce that is simultaneously engaged and reflective. And now they are in their seventies, the pair are thinking about the future of the practice. Binswanger gives an insight as to how this is seen by those who work with them. ‘I can only make limited assumptions about what it will be like without Jacques or Pierre. They’re here and we are working productively together – it is business as usual. However, there is a long-standing plan already put into place regarding the gradual transition of ownership from the founding partners to the rest of the partner group. Nobody will retain shares in the company if they are not active in the practice.’

Not that Jacques and Pierre seem like they are slowing down. While I explore their origins in Basel, they are off to Hong Kong for the international opening of M+, their new museum for visual culture. Digital screens are an essential part of that city’s skyline, but here the screen is part of the building itself rather than something attached. From across Victoria Harbour, digital art can be seen on the façade of M+, but up close the ‘screen’ reveals itself to be a highly crafted surface: LED lights embedded in horizontal bands of concrete and terracotta tiles, which also act as louvres to shade the interior.

As Jacques and Pierre consider the work before them – the National Library of Israel, for example, should complete later this year – there is a sense that the RA exhibition is a moment of culmination. Herzog describes his thinking about the pair’s roles going forward. ‘Sooner or later we, or maybe I, will not be involved in the same close way with each project as I have been.’

One senses though that they will never stop with Basel. Jacques and Pierre are lobbying intensely for an S-Bahn ink between the city’s two main stations and beyond. Love of one’s city is, for Jacques, a universal virtue and perhaps explains the flourishes one glimpses in their work in their home town: the fiery red of the staircases in their Stadtcasino concert hall, for example, or the sudden surprise of seeing a birch tree in the middle of a rehabilitation ward at REHAB. ‘Without being stupidly blind, everybody should love their city,’ he says. For all Jacques’ artworld connections, he’s also a huge football fan and compares his love of Basel to the unbreakable bond he has with its football club, FC Basel. ‘If you’re a fan, you’re dead in a way. You have no choice.’ He’s joking but perhaps Basel is the only arena where agency falls aways and we find a sense of destiny, driving him and the practice forward.

One of the mantras of our age has been ‘think globally, act locally’. It has been used by everyone from Friends of the Earth in the 1960s to Coca-Cola in the 2000s, but it reaches its apogee when applied to architecture. With foundations sunk into the earth, there’s nothing more local than a building. And yet, because of the sheer amount of money and material it takes to build, we know how completely architecture is bound by modern supply chains to the international economic climate, and how quickly can the fame of a great architect spread to the four corners of the world. No architects have grasped this delicious but complex conundrum as well as Herzog & de Meuron.

Tim Abrahams is a writer and editor, contributing to publications including Architectural Record and Art Review.

Herzog & de Meuron is at the RA from 14 July to 15 October 2023.

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door.

Why not join the club?

Related articles

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024

10 RA Schools stories through the centuries

16 May 2024

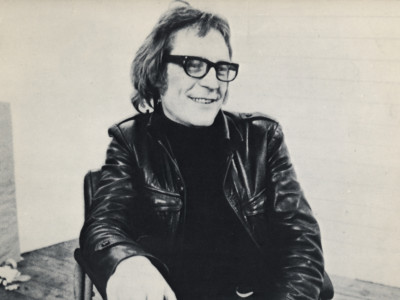

In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

1 May 2024