Rana Begum: "My work is a release, allowing me to feel calm."

By Sam Phillips

Published on 3 June 2020

Rana Begum RA discusses moving studios during a pandemic, its impact on her creative process and how having the children at home has introduced some new qualities into her work.

From the Summer 2020 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA. Rana Begum RA’s solo show at Kate MacGarry, London, is now scheduled for 9 September to 31 October 2020.

I was scheduled to visit Rana Begum RA at her studio on Friday 20 March. But that was the week when everything changed. On the Monday the government asked non-essential contact to cease. Social-distancing measures quickly became widespread. Businesses and other organisations, including the Royal Academy of Arts, closed their doors. Each day brought more grave news, with the dread of worse to come.

My studio visit was changed to a telephone call from my home office. Begum answered from her home and studio, a new building in London’s Stoke Newington, overlooking Abney Park Cemetery. "It’s a really strange and worrying time," said the artist softly down the line."I’m worried about the financial impact it will have on the team, and on myself as well. How can I support everyone?"

Begum creates her site-specific installations, serial paintings and geometric sculptures (No. 814, 2018) with a team of up to four staff – skilled assistants who can no longer work with her in the studio. Mythologised as loners, artists are rarely so, and Begum is a case in point. The recently elected Royal Academician is a very social person, networked within the art world and, in recent years, constantly collaborating with others both in her studio and on residencies and commissions abroad.

"It will also be difficult to be creative now, because I’m in this situation where my studio is stuck in a mess," she continued. "I was in the middle of moving stuff over from my old studio. It will be a really tricky period. And the kids are going to be off school from Monday, so that’s another thing to manage." Yet like the colours of her artworks, Begum errs towards brightness. "I’m trying to see this in a positive way, as I want to adapt to the situation. It’s a good time to reflect and recuperate, and if we’re going to be isolated, that could be interesting creatively."

It’s a good time to reflect and recuperate, and if we’re going to be isolated, that could be interesting creatively.

Most interviews can take place over an hour or two one afternoon, with a writer catching a characteristic slice of their subject’s life. Yet with everything in such flux, a different approach was required. I asked Begum whether we might talk again on the following Friday, once she had begun adjusting to the lockdown. We would go on to speak at the same time over the next three Fridays, a welcome routine where we took stock at the week’s end.

We spoke for an hour at 3:30pm, after Begum had spent the lion’s share of the day homeschooling her two children, Jibril, aged eleven, and Aisha, aged eight. During our next chat, on FaceTime, she gives me a tour of the building. Even when experienced in pixels on my laptop, it is hugely impressive – a whitewashed, three-storey, 5,000sq-ft structure in which the artist can move seamlessly from working life below to family life above. It was a decade-long labour of love, designed by Peter Culley of Spatial Affairs Bureau, and built on the site of a cold, damp warehouse where Begum once worked and lived. Holding up her iPad, Begum shows me round: the basement, which is a workshop with some heavy machinery; the ground floor, with areas for maquettes, models and materials (including scores of cans of spray paint), as well as a staff office and a skylit display gallery; and finally upstairs to generous living spaces with elegant furniture, including a living room where Begum’s two children are devouring their rationed hour or so of screen time.

Clad in silver Scottish larch, the building adjoins several Victorian structures, meaning 12 party walls. The only side with windows is that facing the cemetery – and what windows they are. Continuous sheets of expansive glass plant the viewer firmly in the outdoors, among the majestic oaks, poplars, sycamores and birches of Abney Park, one of London’s ‘magnificent seven’ garden cemeteries, with its 32 acres of woodland and wildlife. "It took us a long time to adjust to this amazing view and this wonderful light that we’re getting now we live here. I feel incredibly lucky. Aisha and I have these moments where we just sit and soak it in: the interaction between the nature and the architecture, as well as our reflections that appear on the window’s surface."

This light-largesse has triggered new memories of Begum’s childhood in rural Bangladesh, which her family left when she was eight to settle in Britain, in St Albans. She was the same age then as her daughter is today. Begum’s memories of Bangladesh first began surfacing with more clarity in her mid 20s, informing her thoughts about her practice. "I realised that my connection to light began very early on. I found it fascinating just to watch the change of light in the rice field, or the water of the bathing pool, which was always flooded in sunlight – I remember my mum telling me off when I sat there staring." The enchanting, myriad ways that light gleams from different surfaces and spaces have remained her abiding obsession.

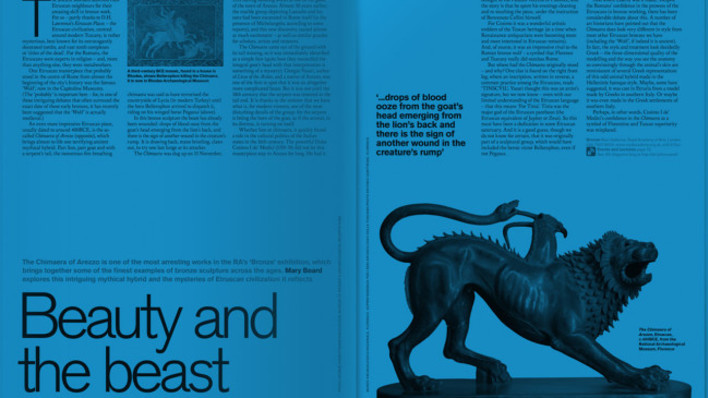

In her wall-based Reflector works, for example, grids of glass automobile reflectors – in two or three colours – form jagged geometric shapes (No. 969 L Reflector, 2019). As one moves around in front of the work, the light bouncing off each reflector modulates, creating a dappled, mesmeric effect, not unlike sunlight glancing off water or, indeed, through the trees of Abney Park. Other series use meshes, nets, folded metal and grids of painted MDF. Using her iPad camera, Begum presented to me one of her Aluminium Box series, mounted on the wall of her ground-floor gallery (No. 988, 2020). Thin, long cuboids of metal were arranged in a pattern on the wall. The front-facing sides were a crisp white, while their right and left sides were sprayed with solid hits of colour. As she moved her iPad to the left or backwards, the colours mingled in unexpected ways, appearing in glowing, misty, mid-tone gradients. "At first I thought the gradients were a mistake, a disaster, because I don’t mix colours. But the more I looked the more excited I became, because I realised the materials were doing the mixing for themselves. I have to be open to mistakes, to chance, to things arising in the process, for my work to move forward."

Works (from left to right): No. 988, 2020; No. 969 L Reflector, 2019; and No. 911 L Fold, 2019

Her industrial materials, unmixed colour, pared-down aesthetic, and fascination for repetition (her works are numbered rather than titled) place her in the slipstream of the post-war American Minimalists such as Donald Judd. "People say Judd’s work is cold and soulless, whereas I think it’s the complete opposite. I’m so moved by interacting with his works, especially by how I experience light when I see them." She discovered Judd during her art foundation at Hertfordshire University, a course that was "incredibly eyeopening." There she embraced every material and technique on offer, from printmaking and textiles to sculpting in metal. "I welded this ridiculous structure that sat in my parents’ back garden for years, and every time people went past it they would question what it was."

Her love of different disciplines persisted, through the Chelsea and Slade art schools for her BA and MA; a period when she assisted Tess Jaray RA (still a great mentor and friend, Jaray’s painting Recollection 2, 1986, has pride of place in Begum’s lounge); until more recent years, when she has enjoyed significant success, with commissions for large-scale installations and pieces for the public realm. For Dhaka Art Summit in Bangladesh in 2014, she made an architectural space with undulating ceiling and walls built of handwoven bamboo baskets, of the type she used to weave as a child with her grandma. Once again, light was foregrounded, filtering through the bamboo to cast sublime shadows; relaxing inside reminded Begum of sitting in a mosque. "I love mosques, for their light and colour and geometry and repetition. You really physically experience the space, and that to me is an experience of the infinite, and a calmness, a way of connecting your mind and body."

"But," she added, "most of my work has a dual experience. There is this loud aspect because of a work’s strong colour and form; then, if it’s a good piece, there is a moment where you get this calm and reflective experience. It’s like life, isn’t it? You don’t have full control over the balance of chaos or calm."

So which of the two had the upper hand, I asked Begum, when we spoke for the fourth and final time, a month into lockdown? In an alternate world, she would have been spending the day testing technical processes with her team, finalising works for her June show at her gallery Kate MacGarry (now scheduled for September) and planning projects in Sweden, Boston and Bermuda, as well as for the Folkestone Triennial (also now postponed, until 2021).

Instead, with some staff furloughed and others working remotely, and with exterior collaborators – from fabricators to art dealers – in abeyance, and Begum’s time taken up with her two children, the rhythm of production has been, at best, staccato. "Mentally it has had an effect on me, not being able to work. My work is a release, allowing me to feel calm."

However, Begum has found that slowing down has its advantages. "When interesting people approach you with opportunities, it’s really hard to say no. But the speed can become too much. And I need time because the work needs the time. I don’t want to be one of those artists who just churns works out. Part of me is appreciating this forced situation – it’s brought me really close to the kids and it is also making me think about the way my work is developing."

During the week, needing to make some work, needing again that calm, Begum had turned to a piece of paper. First she draughted a large grid of small squares in pencil, then she used black watercolour to fill in some of the squares, forming large diamond shapes. She had intended tight control of the strength of the black. Then, perhaps predictably, chaos had ensued. "My children kept asking me questions and interrupting me, and I was frustrated as the marks I then made weren’t perfect." But Begum then made a bit of a breakthrough. "I realised that actually, the interruptions, the mistakes, were amazing. The varied weights of the watercolour as it thinned on the brush – there was this lovely complexity." She paused. "I’m really pleased with the work. And I feel so lucky to have had some kind of release."

She held up her iPad to the sheet of paper, moving it from left to right. The subtle variations of black, fading at moments to a light grey wash, emitted the same dappled effect as the Reflector works. I thought of sunlight through the trees of Abney Park, and then photosynthesis, the chemical reaction of light and matter that enables life to thrive.

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

Related articles

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024

10 RA Schools stories through the centuries

16 May 2024

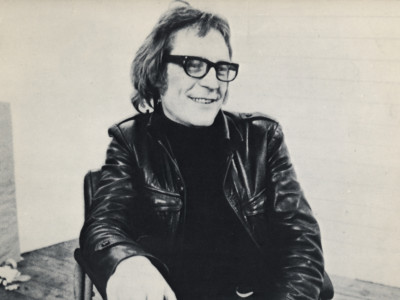

In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

1 May 2024