Charles Jones and his vegetable portraiture

By Felix Bazalgette

Published on 17 June 2020

A chance find in a market unearthed a bumper crop of early photographs by Charles Jones that are now art-historical treasures. Felix Bazalgette samples the artist-gardener's rich pickings.

Felix Bazalgette’s book on the history of photography, Natural Magic, is to be published by Fitzcarraldo Editions in 2021.

From the Summer 2020 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA. Charles Jones’s photographs will be included in 'Unearthed: Photography’s Roots' at Dulwich Picture Gallery. The show is now postponed due to the coronavirus crisis.

As a young man, at the beginning of the 20th century, Charles Jones had occupied a position as the gardener at Ote Hall in Sussex, and was mentioned in a Gardener’s Chronicle article of 1905 for his skill with herbaceous borders and his "delight in his well-trained fruit trees". This article might have been the only historical trace of Jones’s life, were it not for a cache of around 500 photographs which turned up at Bermondsey Market in London in 1981, 22 years after his death.

A photography collector and dealer named Sean Sexton came across the images piled together in a trunk, and was struck by the expertly composed gold-toned prints of plants, vegetables and flowers which, with their austere backgrounds and delicate attention to form and shading, seemed to anticipate interwar modernist photography, despite them having been made around the year 1900.

Over the next few decades Sexton would slowly put the photographs out to auction, raising interest in Jones’ oeuvre piece by piece, while gathering what scant information he could find about the elusive gardener who created them. In the late 1990s, Sexton published a book of Jones’s photographs, and a slew of exhibitions followed.

The idea that these photographs are a remarkable presentiment of modernism was certainly one reason that made the images marketable, in the '90s and now.

Some have compared them to the studies made by the American photographer Imogen Cunningham, who famously produced artful studies of the magnolia flower in the mid-1920s, set against stark, neutral backgrounds.

The German photographer Karl Blossfeldt, who also worked at this time, had developed his own macro camera systems in order to take similar photographs of plants and flowers close-up, revelling in their unfamiliar forms and contours (the philosopher Walter Benjamin was a fan).

Looking at many of Jones's images you have the unavoidable impression that they are portraits of vegetables. There’s poignancy, as well as a gentle absurdity.

But to present Jones’s photographs simply as a prelude to the main show of modernism would be somewhat limited, and in many ways his work is very different to what came later. With Cunningham and Blossfeldt the plants aren’t conveyed as individuals but as specimens, examples of form: clean-lined and curvy, often cropped into abstraction.

Charles Jones, however, seems to have been aiming for something weirder and, to my mind, a little more interesting: looking at many of his images you have the unavoidable impression that they are portraits of vegetables. You see the flecks of dirt hanging off them, the rumpled edges of the photographic backdrop, the scuff marks on the floor as he has moved and repositioned them. There’s poignancy in such details, as well as a gentle absurdity.

My favourites of his images in this regard are the root vegetables, specifically the stout ‘mangolds’ (similar to a beetroot). ‘Long Reds’, ‘Yellow Globes’ and ‘Red Tankards’ with their scuffed surfaces, look like satellite images of an alien planet, while at the same time they exude a strangely human presence, an unflappable dignity.

In many of his images, such as Bean Longpod, there’s a photographer’s delight in form, a gardener’s pride in what he has produced, but also a kind of respect for the vegetable’s own existence – as separate, whole, mysterious.

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

Related articles

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024

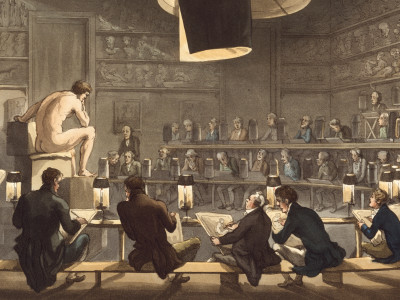

10 RA Schools stories through the centuries

16 May 2024

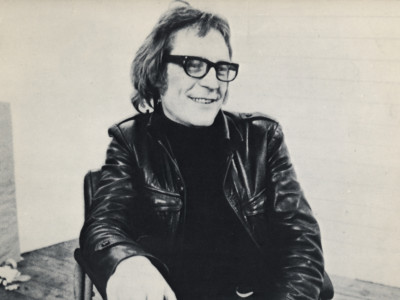

In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

1 May 2024