What are the building blocks of a liveable (and loveable) city?

By Rachel Fisher

Published on 11 December 2018

As part of RA Architecture Studio’s Invisible Landscapes series, urbanist Rachel Fisher weighs up the myriad ways that social technology can help us build human-centred cities.

In 1989 when Back to the Future Part II came out, I was a ten-year-old living in Austin, Texas. The film is set in 2015, and I remember with perfect clarity watching Marty McFly walk into Café '80s, a retro-themed diner in the fictional town of Hill Valley. I couldn’t believe anyone would ever be nostalgic for the 1980s. The '80s weren't even over! Such is the innocence of youth. Now, the hipsters who weren't even born when the film was released are wearing giant day-glow glasses and high-waisted acid-wash jeans. Even the much-derided bum bag has made a comeback for fashionistas. Bad ideas get recycled too.

The film may have failed to predict perfectly the now present future (where is my hoverboard?), but there are things that it got absolutely right. In its version of 2015, mansions that had been built in 1985 had become run down, cars were increasingly autonomous, TV screens were giant and interactive. But as a budding urbanist, what struck me most about the Back to the Future franchise is that the Hill Valley of 2015 is recognisable as the child of the same city of 1985, and in turn the grandchild of the city in 1955.

In Back to the Future Part III we even see the founding of Hill Valley in 1885 – practically ancient history to an American. In thinking about what a future urban society could look like we would do well to reflect on the past. It is tempting to imagine that the city of the future will somehow emerge, fully formed, out of nothingness. And while in some parts of the world this almost seems to be the case, in England, much of what is built has grown out of an existing place. Even the New Town of Milton Keynes, conceived in 1967 as the model of a major modern city, had medieval villages at its heart.

Perhaps the growth of social technologies, such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, will help us build cities that are simultaneously digitally enabled and more human.

Cities have always formed at intersections – places that trade in physical objects and inevitably in ideas. They need three things to function: an economic purpose (jobs), places for people to live (homes) and connectivity between the two (traditionally this has translated into transport, although today’s links are increasingly digital). But to truly succeed, cities need a fourth element: culture. Whether high or low, that culture is made up of incremental elements, which create and reinforce the city's idea of itself over time.

Successful cities are overpopulated with multiple demographic groups competing for space – from the talent pool of motivated and mobile millennials to asset-and time-rich older people who want the buzz of urban environments. In economically vibrant places this also brings issues of unaffordable housing and overcrowded transport. In less successful areas, housing remains affordable and transport underused.

Cities need three things to function: an economic purpose, places for people to live, and connectivity between the two (i.e. transport, although today’s links are increasingly digital). But to truly succeed, cities need a fourth element: culture.

What are the building blocks of a truly liveable – and loveable – city? Perhaps the growth of social technologies, such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, will help us build cities that are simultaneously digitally enabled and more human. While the industrial past saw the segregation of urban uses (factories in one district, homes located upwind in another, shopping and leisure in yet another), technology allows us to blend elements of our lives that were once discrete. This is particularly true for people who make up the non-manual sectors of the economy.

Take for example a typical day for a contemporary professional – they wake up, check social media and emails from bed, head to a coffee shop to finish a report, then on to the office, having missed the morning rush hour. At the office, they can check social media, sort out their bank account, and buy a birthday present for their sister, all from their phone or work laptop. There are questions to be asked about whether working from home while running one's home-life from a place of work is good for you, but this is reality for many people. This change in the way we live has an inevitable impact on the way towns and cities are built.

Successful cities are textured

Tiny elements – from paving stones to door knockers – provide the textures of a city. If you've ever watched a child walk down a street, you'll see them run their hands along walls, drag their feet on the paving stones and pick up every stray leaf and pebble in their path. Although as adults our physical interaction with the environment may be more arms-length, cities need to be human in scale and feel human in their materials, otherwise they will become sterile deserts of plate-glass and steel.

Cities need to be human in scale and feel human in their materials, otherwise they will become sterile deserts of plate-glass and steel.

They are numinous

Looking up from street level one can sense the bigger picture of a city – the heady feeling of encountering something vastly larger than oneself. The 'otherness' of the urban machine can be fascinating and almost frightening, but to urban junkies such as myself it is intoxicating. This kind of experience is most obvious in places like Manhattan, where the grid pattern enables you to see far-off vistas, opening your mind to new possibilities. A similar effect is also at work in medieval cities, where narrow alleyways open onto an unexpected square graced by a church or other monumental building. The layout of medieval towns is the result of organic growth rather than deliberate planning, but such towns are consistently ranked among the most liveable and rewarding of urban environments.

They bring people together

Successful cities have museums, plazas and parks – places where people can gather, whether as individuals or in groups. Such areas can function at a range of sizes and levels of public access (think of the traditional London square where only residents have keys) but all provide opportunities for the chance encounters and exchanges that can make cities so successful.

When thinking about how to design and build the cities of the future it is important to remember these tried, tested and traditional elements. We need to build, and rebuild, places that maintain the messiness of historic cities while integrating the benefits of new technology. Thanks to these technologies, the way we live is changing, and cities must change too. It would be wrong to imagine that a more tech-enabled future would lead to ever sleeker architecture with ever cleaner lines. Technology is becoming more social, and as such it can – and should – be pressed into service to create more social environments. In the same way that the Hill Valley of 2015 retained its town hall from 1885, it is possible to reinvent cities in ways that reflect our human need for connection, both virtual and physical.

(Rachel Fisher) is a civil servant, co-founder of Urbanistas network and co-hosts the podcast (Every Day Design). Illustrations by Leonie Bos

Invisible Landscapes: Environment (Act II) is in the Architecture Studio, the Dorfman Senate Rooms, Royal Academy of Arts, London, until 20 Jan 2019.

Related articles

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024

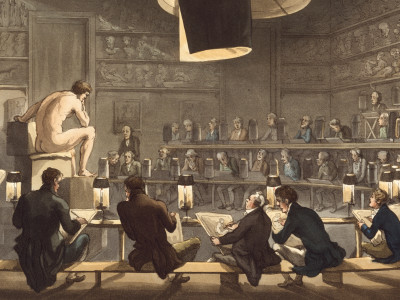

10 RA Schools stories through the centuries

16 May 2024

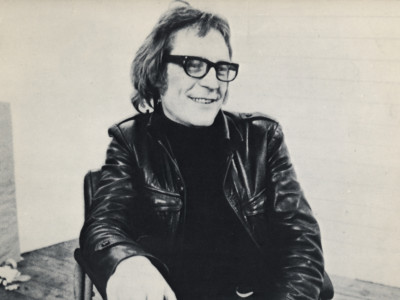

In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

1 May 2024