Louis Kahn at the Design Museum

By Trevor Dannatt

Published on 21 May 2014

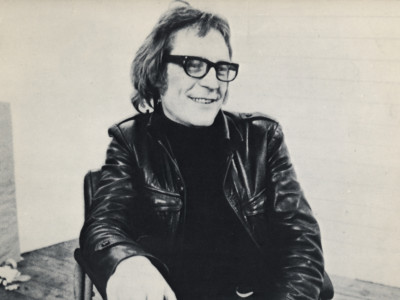

Architect Trevor Dannatt RA pays tribute to Louis Kahn, whose poetic buildings are celebrated at London’s Design Museum.

Lovers of architecture will be heartened to know of the forthcoming exhibition of the work of Louis Kahn, which travels from Germany, landing at London’s Design Museum in July.

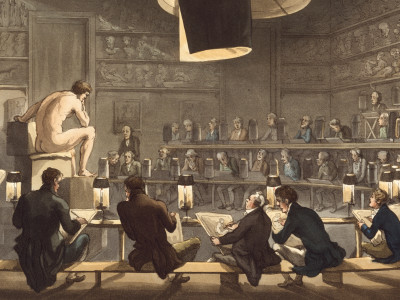

Kahn’s mytho-poetic life seems to follow the fabled rags-to-riches pattern. He was born in 1901 in modest circumstances in Russian-controlled Estonia. A few years later the family emigrated to the US. He was nurtured in Philadelphia and professionally trained at the University of Pennsylvania, where he followed the French-inspired Beaux Arts tradition – based on European academic instruction – which had a serious influence on his thinking.

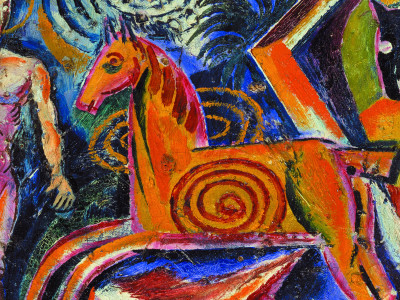

He worked for and with other distinguished architects, mostly on common war and postwar housing problems, and set up his own practice in the late 1940s. His year in Rome at the American School is thought to be his seminal experience. Here his Beaux Arts training helped him ingest Roman forms and grandeurs and later employ them as significant elements in certain buildings, absorbed and regenerated. About this time he received the commission for the Yale University Art Gallery where his latent ideas first achieved built form, though still perhaps in the more International mode popular before the war. Thereafter all his work, private houses to public buildings, proclaim his authorship, a remarkable body of authentic architecture, striding east and west, beyond what few have been able to achieve in more productive practices. Private houses, residential buildings, laboratories, libraries and art galleries, an institution and a Parliament building: all organised on ideal geometries and realised through lucid structure and building fabric.

Colonnade on the North side, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, 1966–1972

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut, 1951–53

Steven and Toby Korman House, Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, 1971–73

Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, 1959–65

National Assembly building in Dhaka (dusk), Bangladesh, 1962–83

In the 1960 Architects’ Yearbook, architects Alison and Peter Smithson wrote on Kahn's city planning ideas, notably those for Philadelphia where he had an uneasy relationship with planning chief Ed Bacon. ‘His ideas were torn apart by specific considerations,’ concluded the Smithsons, and judging by what was published his ideas for Philadelphia stayed in flux. Nothing was achieved, as with the Jewish Community Centre at Trenton, New Jersey, where in a large complex only the Bath House building was realised. Published early, it soon entered the canon. It seems he was at his best working with a specific client: one who wanted to build, was patient and seemingly in awe of Khan's Charisma (with a capital C), as with Jonas Salk at the eponymous Institute for Biological Studies in California.

In their piece, the Smithsons included schematic drawings of some houses featuring very geometric formats, together with evidence of Khan's pursuit of his potent idea of served and servant spaces – a formal organisation of blocks of space formed by walls, static rather than dynamic. The Smithsons somewhat patronisingly (as was their wont) but correctly declared Kahn ‘will soon be a very great architect’ and they also discerned an evident historicism in his theoretical thinking, notably the European historical tradition embodied in the Beaux Art system under which he trained. In Europe concrete prevailed because of steel shortages and, along with brick, it was one of Khan's favoured materials in the realisation of his later works, rather than the inevitable US steel frame. This seemed to attach him at first to European modes. The served and servant spaces idea was exemplified in the Richards Medical Research building at University of Pennsylvania, an early commission. An exoskeleton permits floors that are structure-free while dominant external shafts provide air and lifts and other services – these shafts are much extended to become highly expressive elements that seem to speak of a ‘cutting edge’ institution.

There is perhaps a tendency towards the monumental in the Beaux Arts tradition and Kahn achieved it where appropriate. Otherwise, his buildings exhibit what I would call ‘due order’, following strict geometries, which in his work carry an inherent calmness and gravitas. These qualities are exemplified in the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art at Yale (1968-77), in which two full-height courts subtend the accommodation and on the top floor the basic structure of the building – six by ten square bays – is transformed into a breathtaking assembly of interlinked gallery spaces, each defined by natural light above the sloping sides of the ceiling coffers. Everything is detailed with consummate feeling for fine materials, echoing the centre’s collection, the cream of British art.

Other buildings, notably houses and residential projects, show the same sensibility towards right materials in conjunction, the delights of the physicality of material, density, colour and texture – and eloquent combinations of opposites.

Kahn loved castles and was as fascinated by the spaces hollowed out within their massive walls as he was by the structure of castellar forms. His ability to absorb and regenerate the archaic is outstandingly demonstrated in the National Assembly Building in Dhaka, Bangladesh (1962-83), a vast complex of related spaces and areas for activities. The volumes suffused with light and shade are as expressive of human aspiration as temple, mosque or cathedral.

It is not seemly to write of Khan without referring to the William J. R. Curtis work Modern Architecture since 1900. The chapter on Khan is to be savoured, together with Curtis’s recent major essay in the Architectural Review in 0ctober 2012 arising from the completion of Khan’s final building, the Roosevelt Memorial in New York. One can write but a pale reflection of what Curtis discerns and illuminates. Curtis also contributes to the substantial publication that accompanies this exhibition.

Apart from a practicing architect, Khan was highly regarded as a lecturer and teacher, and an author of a number of now well-known apothegms and sometimes gnomic dicta, poetic metaphors for the essential nature of a building task such as ‘what does it want to be’. He received due honours, gold medals /8et al*. Others would have followed but the fable ended. Kahn died a lonely death in 1974 at a railway station in New York, having returned from the Indian Subcontinent where his magnum opus was only just rising out of the ground and water in Dhaka. He never saw it.

Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture is at the Design Museum, London from 9 July–12 October 2014.

Related articles

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024

10 RA Schools stories through the centuries

16 May 2024

In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

1 May 2024