Laura Knight RA’s compelling Gypsy paintings

By Sasha Dugdale

Published on 9 November 2021

Poet Sasha Dugdale reflects on Laura Knight RA's evocative Gypsy portraits ahead of a major retrospective of the artist's work in Milton Keynes.

From the Autumn 2021 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

Sasha Dugdale is a poet and translator. Her most recent collection Deformations (Carcanet) was shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize.

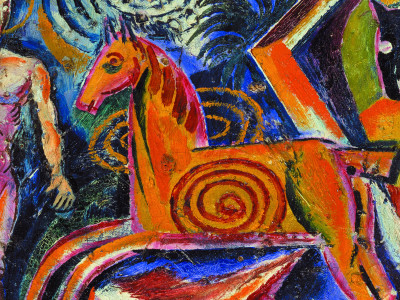

In the two compositions Gypsies at Epsom (1937; below) and Gypsies at Ascot (undated; below) by Laura Knight, which both appear in a new survey show of her work at Milton Keynes Gallery, the artist depicts an older and a younger woman standing together. There is often something in a portrait that catches my attention – a gesture I copy involuntarily as I look. In a recent article for The London Review of Books about Bosch’s Terrestrial Paradise, the art historian T.J. Clark begins by becoming one of the painting’s characters, both bodily and in mind and thought, learning from the inside.

In the same way, looking at these two pictures, I copy the women’s stance, as if trying to learn a language: punching my fists into my pockets and looking down mutinously, imitating the younger woman painted at Epsom. The blue-patterned cotton housecoat

I drag lower with my hands’ weight is tight on my hips over the lime green dress with ruched sleeves – itself worn over a shirt, and decorated with a scarf and a necklace. I wonder at the downcast flushed face. Is the subject resentful, or are the circumstances troubling in another way?

I stand into my light-coloured heeled shoes. They were not bought for me or by me, and are well-used, broad where the older women suffer from painful bunions. But this shift of weight reveals something odd about the picture, a disjunction between the young woman’s heavily planted feet and the intrinsic movement of her body, the flickering skirts. Standing heavily also reminds me that I am closer in age to her companion, in scarf and silk-tasselled shawl, who holds out a small crystal ball between finger and thumb, and has a reserved and shrewd expression. The precise detail of the scene, the wagons behind (miniature Russian terem palaces of extraordinary rickety height), the snooker-ball- sized crystal ball – all of it has the hawk-eyed focus of a Ladybird book illustration, and yet there is something concurrently fleeting and impressionistic about the image.

In Gypsies at Ascot the two women display a hooded watchfulness. Note the careful positioning of their hands: the older woman holds one cupped upwards as if asking for alms, while the younger has grasped her own wrist. Their awkwardness brings to mind early photos of farm labourers, so unused to physical stillness that they lay their hands like wooden spoons on their knees. How long did they pose for Knight? Did they speak? Did she?

Ten years earlier, in 1929, British Pathé News showed a group of women, men and children posing in front of a sign forbidding "gipsies to encamp on the [Epsom] Downs", an area of common land where Roma people had always come for races, selling posies, lemonade and fortunes to racegoers. These frictions endure: an article from 2014 in the Sutton and Croydon Guardian, on the history of "gypsies

in Ewell" and Epsom, has some ugly reader comments below the line, and the new Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, if passed, would go further to criminalise Traveller and Roma lives. Knight, in her attentiveness and her truthfulness, did what few other artists have done and do: she allowed sitters and scene to reject her, her art and her society.

Behind the women are rows of black Rolls-Royces and Bentleys, a reminder of the vast social divisions of the time (Knight herself,

by this time a Dame, famously painted from within a Rolls-Royce at Epsom). The situation of these portraits is not a comfortable one: not in coloration, nor composition, nor context, but it’s not our current understanding of inequality that charges these portraits. Knight has allowed such frictions into the very material of the work.

Laura Knight: A Panoramic View is on display at the Milton Keynes Gallery, 9 Oct–20 Feb 2022

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

Related articles

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024

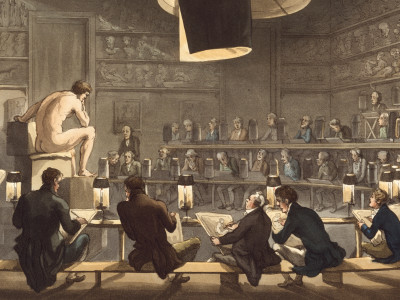

10 RA Schools stories through the centuries

16 May 2024

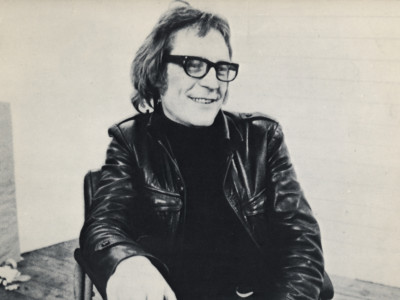

In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

1 May 2024