An architect to the day he died: my friend John Partridge RA

By Peter Schmitt

Published on 12 September 2016

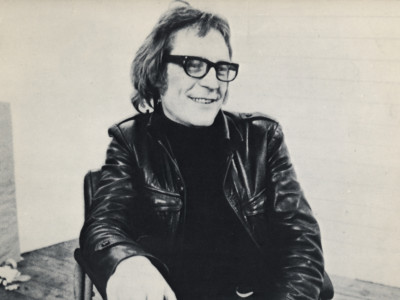

The RA’s former Surveyor to the Fabric remembers his friend and colleague John Partridge, the celebrated architect of housing, colleges and courthouses, who died this summer aged 91.

John always wore a bright tie to funerals. He lived four score and eleven years, outlasting the architectural practice he helped found in 1959 by a score of years. He was made CBE in 1981 and then RA in 1988, dearly cherished, and the first time two Royal Academicians had been elected from the same stable (Bill Howell was RA first, in 1974).

I first met John when I arrived in London in 1972. It was the three-day week with working limited to daylight during the miners' strike. With just an alien's card and a fistful of coins, I spent the day ringing around for work. I was steered towards the office of Howell, Killick, Partridge and Amis (HKPA) at 20 Old Pye Street. There I was interviewed by John Partridge and Bill Howell in a Japanese Ho-o-den of nageshi and ramma in raw pine with hessian panels and a timber slatted ceiling (an HKPA trademark) that was their office. We talked about Louis Kahn and architecture. Bill was a natural communicator and teacher, enthusiastic, with an intuitive mind. John was more patrician, with a gentle English wit and bucket loads of kindness. I instantly wanted to be part of HKPA.

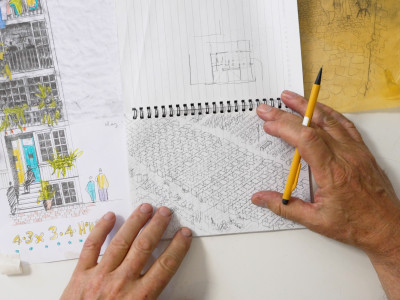

The office was well organised and we worked to regular hours. The HKPA aesthetic was introduced to new recruits by day trips to their buildings in Oxford (John's) and Cambridge (Bill's) and latterly to Trevollard, Cornwall (Stan Amis's) and later still to Jersey to celebrate the Hall of Justice in Trinidad (John's). Sketch designs rained down from Bill: “When in doubt, draw it out,” he enjoined; “Don't reinvent the wheel."

Concrete was John’s material of choice, as it was for many architects working in the 1960s and 1970s. Yet John’s approach to the material was remarkable in its thoughtfulness and sensitivity, as he relayed in a conversation with Elain Harwood of Historic England at the RA in 2007. “We were interested in using materials,” John said. “The external skin of a building is only concerned with modifying climate and to allow light to get in. The skin in concrete is quite thin. You get thickness by projecting windows out to give reveals that grade light into the building.” Close to John's heart was the unbuilt Heythrop College (1965–69), Oxfordshire, where the language of precast concrete was evolved, and St Anne's College (1962–68), Oxford. But the work John was referring to here was the Hilda Besse building at St. Antony's College, Oxford (1966-71, Grade II Listed) – the project that gave him greatest pride and was deemed by many to be his best.

The Hilda Besse building is like a jewel box: nothing can be added, nothing taken away. Every element is the logical outcome of the structural thinking, consummate and logical down to the furniture. The precast concrete cladding John called “elevational plumbing” (John was skilled in drains), “so you don't allow rain to wash down a building and disfigure it,” he explained to Harwood. John generated an entire geometric system in three dimensions. The "diagrid", as he called it, of rooflights on the diagonal for the Dining Room ceiling, would later prove influential for Foster and Partners’ Great Court at the British Museum. The building’s entrance sequence, as John once explained to me, harkened back to Bernini's Scala Regia at St. Peter's in Rome. Such was John’s ability to think and design in the round.

If Bill was the Victorian Gothicist of the practice, who would start afresh when faced with budget or planning obstacles, John was the chess player, with each design move a progression, following the rules of the design game. He was born in North London and won a scholarship to grammar school. His parents moved to South London to be close to the City of London's playing fields, after his gifted brother Peter won a scholarship there. When his father was taken ill, John gave up school and took a job at the London County Council’s (LCC) public health department. He joined the LCC training scheme and enrolled at the Regent's Street Polytechnic, now University of Westminster, where he studied part-time (at night over nine years). The teaching there still was in the Beaux-Arts tradition. John’s final examination began on day one with an esquisse or rough sketch of a design idea for a building, when he then had four days to develop it without deviation or hesitation. He was awarded a Distinction, with this classical training never leaving him.

In 1950, John joined the LCC’s architects’ department which had just regained control over housing. There John met his future partners Howell, Killick and Amis. Together they designed a scheme of 2,000 flats for a site at Roehampton on the edge of Richmond Park. “The cladding,” as John explained, “is thus an example of 'process design', where the resultant aesthetic derives from the process of construction.” The six towers were a homage to Le Corbusier in a Capability Brown landscape, which John remoulded, directing a bulldozer from one of the blocks. Alton West, as the estate is now known, is regarded as a masterpiece of the era.

These "troublemakers", as John dubbed the quartet, then took a leap of faith, John more so as breadwinner for his entire family. Together they founded in 1959 Howell, Killick, Partridge, with Amis joining in 1961, hoping to win the Churchill College Cambridge competition, one of the most significant post-war projects. They came second (due to cost), but were the critics’ favourite, and never looked back. The impact of their vision in precast concrete, arrayed around a reinterpretation of Stourhead (a Palladian house in Wiltshire), was immense. John always had a ready grasp of historical models and a deep understanding of how buildings are put together.

HKPA was structured around projects, a partner in charge and a lead architect, and built on teamwork with input from consultant engineers and a quantity surveyor. John kept a weather eye on cash flow and profit margin – with Stan Amis – keeping the practice afloat in lean times with council housing (Russell Road 1971–81 and Somerville Road 1973–78). John knew everyone in the building profession and could put together speakers for a conference at the drop of a hat.

For 21 years after Bill Howell's tragic death in a car crash in 1974, John shouldered responsibility for HKPA. The pundits gloss over this huge and lucrative body of work, including the Naval Base at Devonport (1971–80), prisons (Belmarsh, 1983–90) and law courts, with the occasional competition thrown in: Leeds Playhouse (1985; a circus big-top of two theatres) and Glasgow Concert Hall (1986; a brilliant urban planning exercise from John's sketches and design elements). John never lost his zest for a good competition.

Three courthouses, at Warrington (1985–91), Basildon (1986–90) and Haywards Heath (1987–91), came into HKPA about the same time. John eschewed Bill's use of rectangles with their corners cut off to ease circulation and re-introduced the structural column to punctuate corners. As concrete became unfashionable, John, ever resourceful, turned to brick. Warrington was a new generation of Combined Crown & County Court Centre, designed in Bill's relaxed groupings of principal spaces under hipped roofs, linked together with the mortar of circulation under flat roofs. John chose Warrington as his Diploma work upon his election to the Royal Academy in 1988 and submitted a coloured Front Elevation, now in the RA Collection. These courthouses were a master class in discrete circulation, whereby the public, judge, jury and persons in custody “can only meet up in the courtroom." Much of this was worked out earlier on, including the pivotal court hall as waiting room, in Medway Magistrates Court (1972-79).

This was key to John's planning of the Hall of Justice (1978–85) in Port of Spain, Trinidad, and winning that international competition outright. Sixteen civil and criminal courts, out of twenty-eight overall, encircled a vast Court Hall at its heart, filling the entire urban block. It is a monumental composition, symmetrical on both axes in the classical tradition. John reverted to the solidity of chamfered corners that was HKPA's signature, but this time the concrete was seismic resistant. He also took advantage of the sun's position on the Tropic of Cancer so that at noon, when it always sits vertically overhead, it would shine down the full height of the two octagonal stair cores, a stunning tour de force to draw you in, as an insect to light. Its cascade of tightly organised forms and its complexity and clarity of layout and circulation stand as a swansong and epilogue to HKPA's rich language of cast and pre-cast concrete construction. It has been looked after immaculately by the Trinidadians ever since and is featured on tourist postcards.

Lastly comes Chaucer College (1989-92), Canterbury, for a Japanese educational trust (Shumei Foundation), a commission John was particularly fond of. The planners wanted a Japanese look, but John wanted an English college. A happy compromise is the result, with John's curving roofs and expressed steel structure held aloft on brick walls, visible inside.

When HKPA ceased trading after 36 years in 1995, John had to deal with the messy breakup of the partnership and the heartache of making the whole practice redundant in a single day. He spent his remaining years in great demand, judging competitions, chairing committees, examining, consulting to the Foreign Office and, in particular, at the RA, which he really loved. “However, the thing he valued most in his career,” as his son Richard testifies, “was his professional status as an architect.” Although he hadn't practised for over twenty years, he was still able to call himself an architect, until the day he died. His contribution to what HKPA produced under his watch, and the quality and magnitude of his achievements, have not been properly credited. His best buildings are a joy to encounter and his attention to detail makes them stand the test of time. Everyone who knew him will miss his three-dimensional mindset, his engaging sense of humour, his technical skill and creative flair, and his sure, twinkling eye.

Adapted from the eulogy given by Peter Schmitt at John Partridge’s funeral.

Related articles

In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

1 May 2024

Crunch: inside the first Architecture Window display

14 February 2024