Introducing Bêka & Lemoine

By Edwin Heathcote

Published on 8 August 2023

Edwin Heathcote meets the architectural filmmakers whose documentary of life in a rehabilitation centre is featured in the RA’s Herzog & de Meuron show.

From the Autumn 2023 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

There is always something faintly ridiculous about avant-garde architecture, a sense of detachment from the reality of everyday use and the mundanity of life as it is actually lived. And few artists have ever captured the essence of this discrepancy with such brilliance – and such forgiving warmth – as husband-and-wife filmmakers Ila Bêka and Louise Lemoine do in their 2008 film Koolhaas Houselife.

Seen through the eyes of the imperturbable housekeeper, Guadalupe Acedo (who emerges rising on a hydraulic floor), the innovative interior details of Rem Koolhaas’s house in Bordeaux for a wheelchair-bound client are brought into harsh contact with the particular problems of cleaning an epic structure. This might seem like an entirely new form of architectural critique but a friend recently pointed out to me that, in one scene in the documentary, a TV is playing Jacques Tati’s 1958 film Mon Oncle, a gentle French comedy precisely about the pretension of modern architecture. Tati’s character, Monsie Hulot, is from the old town, out of place and uncomfortable in the technical perfection and sleek modernity of a modern house. But his clumsiness is our humanity, our attachment to the familiar. That glimpse of Tati is far from accidental.

I spoke over Zoom to Bêka and Lemoine in their Venice studio. "We both thought that Mon Oncle was the best film about architecture," Lemoine tells me. "We tried to learn from Tati how to use humour as a critical tool, a lighter way to understand. Mon Oncle is about the confrontation between two worlds, the traditional and the modern. In a way Guadalupe plays that same character, illustrating the gap and the absurdities of architecture."

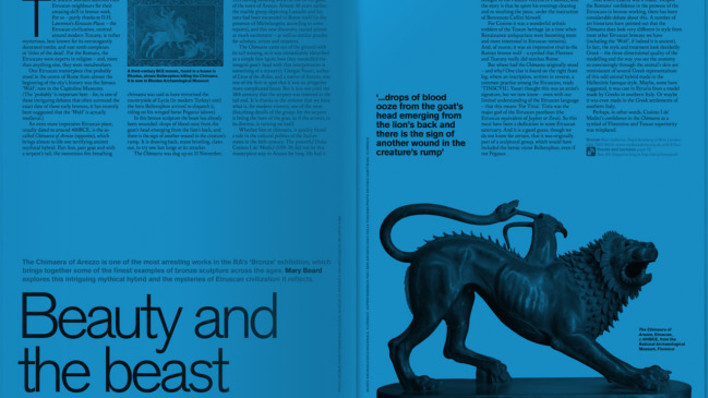

What is striking about both films though, with a half-century gap between them, is that, while critical, they are not dismissive. Koolhaas’s villa is a striking and beautiful dwelling and Houselife is a broadly affectionate portrait. It was only while reading up before the interview that I saw something I should have registered before: the client for the house was Lemoine’s father, Jean-François, who had been paralysed by a car accident. That makes their film Rehab from rehab, on show at the RA’s Herzog and de Meuron exhibition, far more poignant. The film explores the Swiss architects’ design for a neurorehabilitation and paraplegiology centre just outside Basel. Herzog & de Meuron has become known for their blockbuster cultural buildings, from Tate Modern to Hong Kong’s M+ via Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie concert hall – all strikingly inventive, solid, powerful and brilliant structures which have redefined the architecture of the arts. But their attention has always been spread much wider than just this sector.

'Rehab from rehab' trailer by Bêka & Lemoine

An edit of Rehab from rehab is shown in Herzog and de Meuron in The Gabrielle Jungels-Winkler Galleries until 15 Oct.

Rehab from rehab is a film about how architecture can attempt to accommodate a radical change in the body. It opens with what looks like a moon being slowly revealed. In fact, it is a skylight, one of the building’s most famous innovations. People who have been upright all their lives suddenly find themselves here, horizontal, confined on their backs. The windows in the ceiling allow them to see the sky, the clouds, to dream, perhaps. It is a poetic view of architecture but also deeply practical and the film is a moving testimony to how architecture can improve lives. It begins with a quote from Lemoine, about her childhood years with her newly disabled father. "My childhood faded away in rehab centres. The worst spaces I have ever experienced in my life. If today I make films about how space affects people it is probably because of these difficult years."

We don’t make films about architecture, but about the way people behave in space and connect. In fact, we talk about everything except architecture.

Ila Bêka

If the traditional medium for representing architecture has been the photograph, often without people, presenting a heroic image of architecture as sculpture, Bêka and Lemoine do something different. People are very much the soul of their moving images. Their 2017 film Moriyama-San, follows the eponymous architecture patron in his quirky Tokyo house, designed by Ryue Nishizawa. A curious character who sleeps on the floor and practises what the filmmakers dub ‘acrobatic reading’, he is a man who truly inhabits his house, finding places to suit reading particular books, legs dangling from a ledge or stuffed into a space beneath the ceiling. This is not architecture as status symbol but as an armature for active inhabitation. Barbicania (2014) portrays the strange, almost perfectly self-contained Brutalist world of London’s Barbican, from its tropical greenhouse to its breezy balconies, while in Gehry’s Vertigo (2020) the Bilbao Guggenheim’s exterior is explored Alpinist-style like a rock formation.

Their latest project Homo Urbanus is a global odyssey, a seemingly epic undertaking to capture street-life in cities from Bogota to Shanghai via Naples and Venice. An immensely engaging series of films, in some ways it returns to Tati, not in comedy but in its awe of the inventiveness in the use, adaptation, appropriation and occupation of public space. For a couple who are the pre-eminent architectural filmmakers of the age, it is generous and compelling but it is rarely simply about buildings. "We don’t make films about architecture," Bêka tells me, "but about the way people behave in space and connect. In fact we talk about everything except architecture."

But so eloquently.

Edwin Heathcote is the architecture and design critic for The Financial Times.

An edit of Rehab from rehab is shown in Herzog and de Meuron in The Gabrielle Jungels-Winkler Galleries until 15 Oct.

Ila Bêka & Louise Lemoine will join a screening of the full film on 13 Sep, in the RA’s Benjamin West Lecture theatre.

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door.

Why not join the club?

Related articles

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024