Why is Flaming June iconic?

By Rosalind Jana

Published on 13 February 2024

Flaming June is one of the most reproduced images in Victorian painting. What makes an artwork seize the public imagination in ways that give it a life far larger than its own?

From the Spring 2024 issue of RA Magazine, issued quarterly to Friends of the RA.

A woman dreams. She is curled in on herself like a cat, head resting delicately in the crook of one arm. Her hair is long and red, her body swathed in a diaphanous orange gown that shows just enough to be titillating (long legs, the outline of a nipple) while providing sufficient coverage and saturation to make the canvas blaze.

Frederic, Lord Leighton PRA’s Flaming June (c.1895) is a summery, sexy work: the epitome of picturesque indolence with its slumbering figure lulled by sea breeze and the scent of oleander, white impasto sunlight dancing on the Mediterranean behind. Currently on show in a free display at the Royal Academy’s Collection Gallery, this drowsy work is enjoying a homecoming of sorts, returning to the site of its first outing 129 years ago. Painted during the last gasp of the 19th century, when Leighton, the then-President of the RA, was enjoying recognition as one of the period’s most admired artists, Flaming June is a vivid fusion of old and new. With its neoclassical leanings and pose borrowed from Michelangelo’s sculpture Night in Florence’s Medici Chapels, the scene typifies Leighton’s reverence for historic tradition and technique, while tapping into the peculiarly Victorian taste for gorgeous, comatose women: the ‘sleeping beauty’, a recurring figure in art, literature and urban legend.

This particular beauty remains tantalisingly anonymous. Unlike her Pre-Raphaelite sisters, this is no Shakespearean victim or Roman goddess, no Arthurian legend resurrected with plump lips and full eyebrows. Asleep, the woman is unmoored, drifting mysteriously in her gleaming gilt frame.

Even those who do not know the painting’s name nor that of the man who created it might still recognise the image being described. Since its arrival in the art world more than a century ago, the fortunes of Flaming June have waxed and waned, dipping into obscurity before flaring back onto the world stage via a series of extraordinary events culminating in a new nickname (“the Mona Lisa of the Southern Hemisphere”), and the kind of visual fame that ranges from nods in American Vogue to decades of citrus- bright posters decorating student halls of residence.

Flaming June was exhibited publicly at the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition in 1895, the year before Leighton died. Her cadmium-hued gown was emblematic of the painter and sculptor’s self-confessed “fanatic preference for colour”, and with her languid pose embodied Leighton’s vision of “art for art’s sake”: a philosophy that prioritised a painting’s formal qualities and ability to conjure pure beauty. Those qualities were commended by The Times – Leighton’s draftsmanship skills and command of the “complicated line” coming in for special praise.

This line was complicated in multiple ways, not least in the deliberate, anatomically unlikely lengthening of the sleeper’s thigh and neck such that her body created an almost perfect circle.

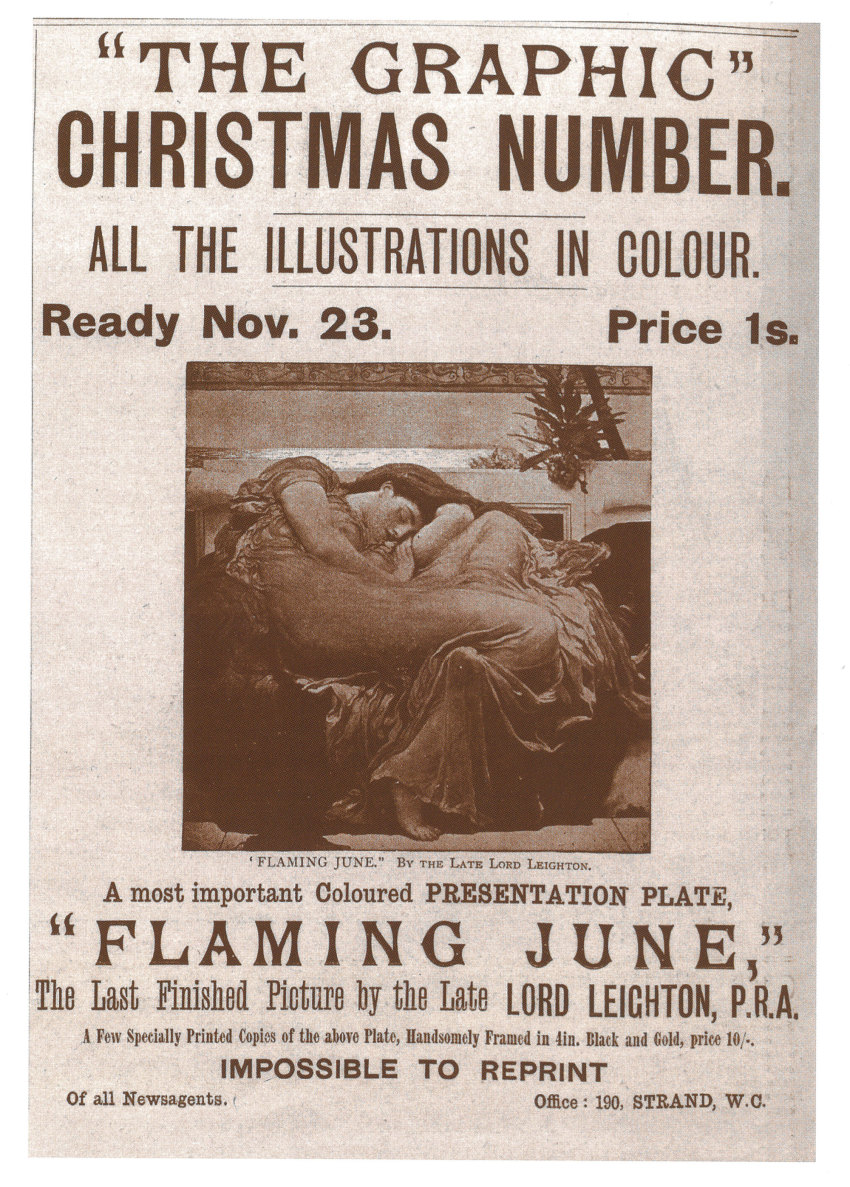

Since her earliest days, Flaming June’s popularity has been enmeshed with her reproducibility. The painting was first bought by William Luson Thomas, the owner of the popular weekly arts newspaper The Graphic. After Leighton’s death in 1896, Thomas capitalised on the public’s interest by displaying the painting in the window of the paper’s offices. Later that year, he offered a coloured presentation plate with the Christmas issue – which, for an extra 10 shillings, came framed. A mass-produced engraving could travel much further than a canvas, taking Flaming June out into the nation, where she might slumber on walls or float among the domestic details of people’s lives.

However, like the many Victorian bestselling novels whose titles and authors have long since vanished into the ether (ever heard of Marie Corelli or GWM Reynolds?), this might have been the beginning and end of Flaming June’s reputation. Indeed, for many decades this seemed the most likely outcome: the painting changing hands several times, loaned to galleries and returned, inherited, sold, lost, and eventually rediscovered behind a wall, or so the story goes, by a builder who was demolishing a house on Clapham Common in 1962. The builder sold it to a framer for £60, who in turn sold it to a barber, who sold it to the art dealer Jeremy Maas, who sold it to Luis A. Ferré, a Latin-American industrialist and former governor of Puerto Rico, who was looking for artworks for his newly created gallery, the Museo de Arte de Ponce. Ferré “fell in love with it at first sight” and parted with £2,000 for the painting.

It was an unusual but perceptive choice. In the early 1960s the Victorians were still hopelessly out of fashion, yet to enjoy the resurgence of interest that would come at the end of the decade. Leighton, with his neoclassical stylings and romantic sentiment, was a relic of a fustier, dustier period. But in Flaming June’s new home in Puerto Rico, her star slowly began to rise again, helped along the way by an appearance on the cover of Maas’s landmark 1969 book Victorian Painters and, in subsequent decades, by an extraordinary wave of merchandising that saw Leighton’s sleeping beauty grace everything from fridge magnets to t-shirts and coasters.

This is the linear story of Flaming June’s change in fortunes, but it doesn’t quite account for the reasons why a painting like Leighton’s enters the public consciousness – especially when it’s the sole work from an artist’s wider oeuvre to do so. It’s easy enough to understand why a Klimt or a Van Gogh ranks among the world’s most popular artworks. The Kiss or Café Terrace at Night (or, of course, the inscrutable Mona Lisa herself ) have their own narratives of ascendancy, but now possess the inviolable status of masterpieces created by master artists whose every sketch, scribble and minor work is of interest. More curious are those paintings that figure as outliers, achieving a special or even iconic status that means they live on, sometimes independently of their original context and creator.

There are a thousand routes towards renown, some more circuitous than others. A painting can achieve fame by notoriety – Quinten Massys’ mean-spirited The Ugly Duchess comes to mind (c.1513) – or through pure mass appeal. Vladimir Tretchikoff ’s kitsch portrait Chinese Girl (1952) could hardly be described as a masterpiece but has sold millions of lithograph copies worldwide, with the original fetching nearly 1.5 million dollars at auction in 2013. Some are immediate sensations – Grant Wood’s American Gothic (1930) – while others, like Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (c.1818), had to wait for critical reappraisal in the latter half of the 20th century to find a wider audience. Some become the epitome of a particular style, such as Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Swing (c.1767-68), which is often described as the pinnacle of Rococo. Some are parodied to the point that they occupy a uniquely identifiable position in pop culture (see, again, American Gothic).

One can grasp for the connecting threads or points of overlap between these disparate works. Flaming June and The Swing, for example, both benefit from mild erotic thrill, flouncy dresses and the institutional backing of a gallery in which it is one of the most prominent works (Fragonard’s painting hangs in the Wallace Collection). But any serious attempt to find a grand, unifying theme will likely end in disappointment. A pretty face, a good story, the shock of the new, the re-evaluation of the old, art market currents, collectors’ whims, a good licensing deal, expiry of copyright, the atmosphere of a nation or era: the fate of a painting is reliant on multiple creative, commercial and social factors. An element of mystery might help grease the wheels, queries about the identity of a subject or the line between document and satire ensuring that people will discuss it. Flaming June has certainly benefited from its ambiguity, its slumbering figure inviting both curiosity and imaginative projection.

Really, this vexed consideration of what makes a painting ‘iconic’ touches on something trickier. It speaks to deeper fears and faiths, asking us to grapple with the more intangible idea of quality, as well as what a work stirs in its audience. Is there something unique about Flaming June compared to Leighton’s other paintings? Something that coheres in mood, subject, composition and so on to induce the kind of wonder and serenity that makes it especially deserving of fame? Or is its repute reliant on its repetition – like the visual equivalent of an earworm? Now the painting has returned to the Royal Academy for a year, one can chew on these questions in person, facing this “gorgeous piece of flamboyance” (to borrow Samuel Courtauld’s words) in all her 120cm-by-120cm glory, rather than via a thumbnail on Google images or a thin, glossy poster, the colours slightly skewed.

Rosalind Jana is an arts and fashion writer whose work appears in publications including Vogue, Apollo and frieze.

Enjoyed this article? Join the club

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

Related articles

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024

10 RA Schools stories through the centuries

16 May 2024

In memoriam: Mick Moon RA

1 May 2024